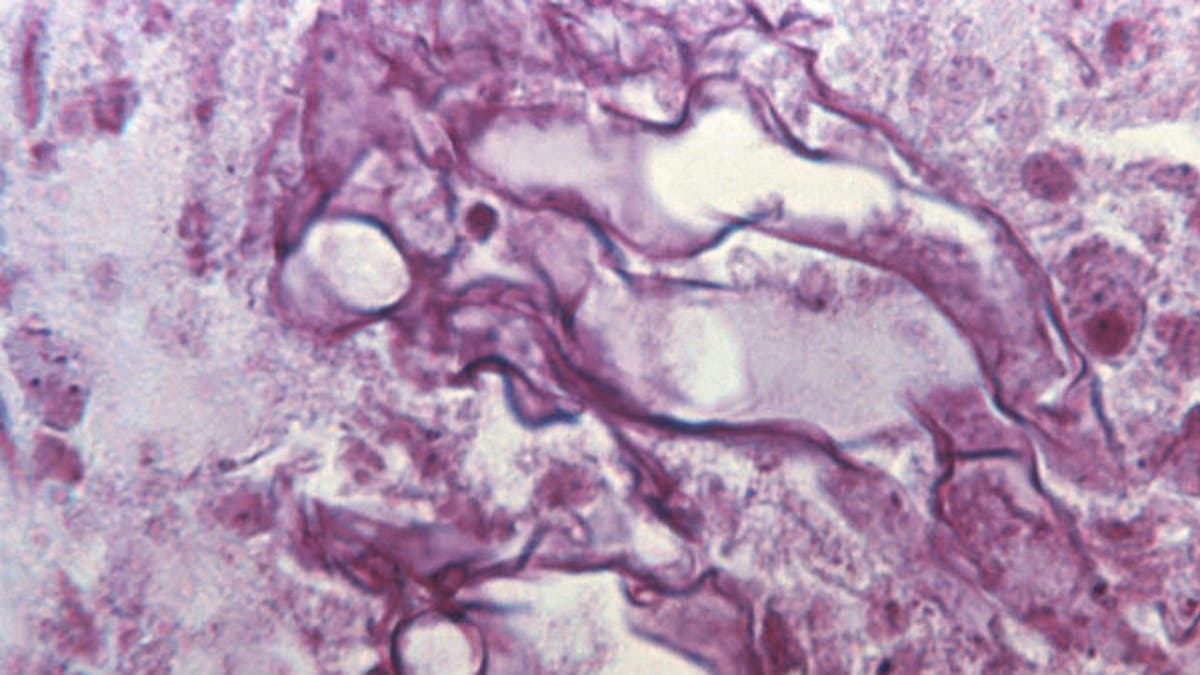

Tissue sample from a patient ill with mucormycosis. (CDC/ Dr. Lucille K. Georg)

Yesterday, there was a very well-written story on the front page of the New York Times about an outbreak of a deadly fungal infection among patients at Children’s Hospital in New Orleans.

As this story was being released, I happened to be attending the 2014 Milken Institute Global Conference in Los Angeles, moderating a session titled, “Revenge of the Superbugs: How Can We Outsmart Killer Microbes?” There were many brilliant physicians on the panel, including Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The session focused primarily on the global problem of infection control: How potentially fatal pathogens are lurking in many hospitals, how hospital-acquired infections have led to the deaths of thousands of people in the U.S. and how bacteria are becoming resistant to most of the antibiotics that we use today to treat infections.

Naturally, I started the session with a discussion of the outbreak at Children’s Hospital in New Orleans. Between 2008 and 2009, five children of different ages died of various causes after being exposed to an outbreak of the flesh-eating fungal infection mucormycosis. This type of fungal infection, though rare, is becoming more common in many health care settings.

What is shocking in this case is that this fungal organism most likely spread through contaminated bed linens, towels or gowns used in the hospital. Children’s Hospital in New Orleans is typically a shining star, in terms of the treatment of pediatric illnesses – but by the time doctors and hospital workers identified the fungal outbreak, it was too late. Physicians did not connect the cases of mucormycosis occurring in the hospital until 10 months after the first patient had died – and did not fully disclose the outbreak to the public until this month.

The breakdown that led to this outbreak at Children’s Hospital is not surprising to me. Why did the doctors not connect the cases? In my opinion, there was poor communication and poor follow-up by medical personnel – particularly by the infection control section of the hospital. Every hospital has an infection control panel which includes doctors and nurses who must track rates of infection and atypical cases. One of their jobs is to make sure that there are no organisms lurking within a hospital’s walls or premises that may infect already-ill patients.

When the hospital finally pinpointed linens as the vector for the spread of this fungal infection, they also found out that hospital workers were handling linens improperly. Notably, workers were unloading clean linens on the same dock where medical waste was being removed from the hospital. This is like cooking a meal in your toilet.

Furthermore, soiled, used linens were being transported on the same carts as clean linens. And standards for the storage and proper cleaning of linens at the hospital were also found to be lacking. All of these factors may have contributed to the tragic deaths of five already-ill children.

Thankfully, the CDC is taking action to ensure that as soon as hospitals discover potentially deadly microorganisms lurking on their premises, they report them. If we’re going to win the battle against superbugs, we have to have transparency.

Looking back, it is easy to see the value of transparency when it comes to outbreaks. When SARS emerged in China, the Chinese government attempted to conceal the seriousness of the outbreak – leading to further spread of the disease.

However, with the guidance of the CDC, the Chinese government began to see the light, and realized that early reporting was essential in controlling outbreaks. Since that incident, the Chinese government has become quite transparent when it comes to outbreaks in their territory.

The CDC is optimistic that by monitoring outbreaks and making early diagnoses with new technology, they can keep Americans safe. However, I still question the honor system that they must rely upon, which rests on the principle that hospitals around the country will report their problems and inform the public in a timely manner.

Not only do health care workers have to do a better job of spotting these problems, but hospital administrators and governing boards must be held accountable as well. Everyone within a hospital has a duty to make sure that the ultimate product which they are responsible for – healing – is well protected.