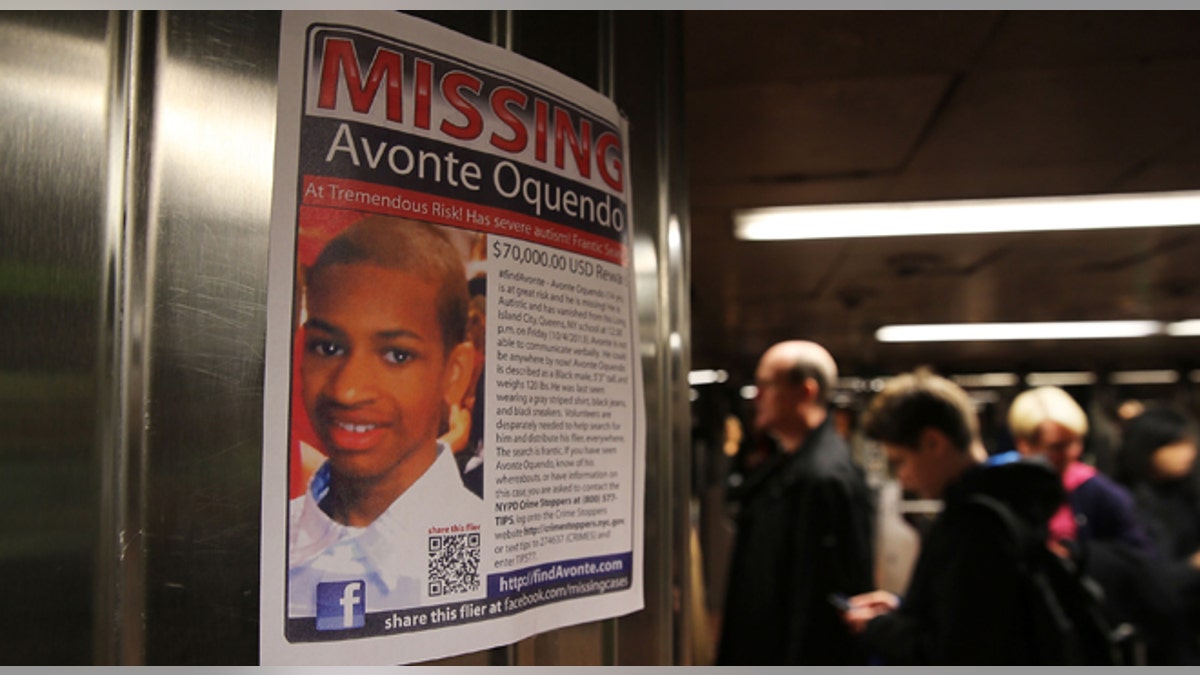

A poster for a missing autistic 14-year-old named Avonte Oquendo hangs in subway station on October 21, 2013 in New York City. (Getty)

As the tragic end to the story of missing 14-year-old Avonte Oquendo unfolded in New York, the very serious issue of children with autism who have a tendency to wander is again brought to light.

The wandering behavior this young boy exhibited is called eloping, which means he left a safe location on his own accord without asking permission or being given a direction to do so.

According to a 2011 report by Kennedy Krieger Institute's Interactive Autism Network, 49 percent of children with an autism spectrum disorders have attempted to leave a safe environment.

According to the report, 56 percent of parents say eloping is one of the most stressful behaviors they encounter while caring for their children with autism.

Eloping, also referred to as bolting, darting, or running, is a potentially dangerous behavior that has led to 22 deaths in just 20 months between 2009 and 2011, according to the National Autism Association. Of those 22 deaths, 20 were caused by accidental drowning and two were hit by vehicles.

The danger of elopement comes in many forms; from running into traffic to going with a stranger, the hazards are around every corner.

Some children with autism are nonverbal and therefore cannot communicate without a support, such as an augmentative communication device, a Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) board, on which a child can point to pictures of his wants and needs, or sign language.

If a child elopes without a support, or in the case of sign language, encounters someone who does not speak the language, it could be incredibly difficult or likely impossible for the child to communicate any personal information which would ultimately lead to his safe return home.

Some children with autism do not respond to their name being called or answer when an adult approaches them and engages them in conversation, which can hamper rescue efforts, as well.

In addition to difficulty communicating, many children with autism do not have an age-appropriate understanding or awareness of safety procedures, such as checking for cars before crossing the street, walking within a cross walk or avoiding strangers.

David Celiberti, PhD, BCBA-D, is the executive director of The Association for Science in Autism Treatment, a not-for-profit organization committed to providing evidence-based information for families of children with autism, and has seen firsthand the importance of addressing the issues surrounding elopement behaviors.

"We have to remember the ‘I’ in IEP. Goals should be tailored to the child's age and setting,” he said, referring to a child's Individualized Education Program, the legal document which dictates what, how, where and with whom the child will learn. “The whole team must address the goals and data must be collected to make sure the child is making adequate progress in those skills."

There are resources for parents and caregivers when it comes to eloping behavior. The Big Red Safety Box is a resource created by the National Autism Association for The AWAARE (Autism Wandering Awareness Alerts Response and Education) Collaboration. The cost of the box is $35.00 and includes a variety of items, including five laminated adhesive stop signs to be hung on doors and windows as cues for children to stop before leaving, two door/window alarms with batteries, and a red safety alert wristband that says “I have autism.” The wristband will alert community members or first responders that the child has the disability and may not verbally respond.

There are also currently two Big Red Safety Toolkits available, one for caregivers and one for first responders, which are free and available for download on the AWAARE website. The comprehensive kits help caregivers and first responders organize important information in case of an emergency, such as the child's description, preferred toys and locations within the community, and contact information for The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and local media contacts.

Though attention to eloping and resources for the behavior are more recent, the issue itself has been on the minds of those in the autism community for a long time. One New Jersey mother took action many years ago when her son, now 22 years old, was diagnosed with autism, then a relatively unknown condition.

Joanne S., who preferred not to use her last name to protect her son's privacy, saw a "Deaf Child Area" sign alerting motorists to drive cautiously in a neighboring town. She asked the head of the Department of Public Works in her hometown if he could order a similar sign for her street, as her then 4-year-old son had taken to wandering from her home frequently.

A few weeks later, the sign was up and when she moved to a new home within town a few years later, the sign was relocated immediately. Today, towns have the option of installing "Autistic Child Area" signs, which were not available years ago.

"Brandon hears but he doesn't understand,” said Joanne. “He still has not learned the concept of danger. Whether the sign works or not, I'm not sure, but I know I'm conscious of it, so I think if people see it, they'll be conscious of it."

As members of the community become aware of the issue of elopement, a new resource may soon be available for parents of children with autism who wander. Based on the efforts of parents, caregivers and professionals to educate the public on this pressing issue, and with the recent tragic death of Avonte Oquendo, people are now taking notice, and more importantly, action.

With Avonte’s mother, Vanessa Fontaine standing close by, Senator Charles Schumer announced on Sunday new legislation called "Avonte's Law," a measure that seeks to create and fund programs that will provide optional GPS tracking devices for families of children with autism.

Despite parents' and educators' best efforts, statistics show children with autism may wander from the safety of their home or school, and be met with danger at some time in their life. All involved in the care of children with autism will continue their mission to keep the children safe and to educate the community about potential hazards as a means to prevent further tragedy. Though a seemingly overwhelming task, it's one that cannot be avoided.