(Hawaiian Queen Company)

“No bees, no honey; no work, no money” is a way of life for Michael Krones who lives on the Big Island of Hawaii in the town of Captain Cook, which sits atop the ancient fault that created Kealakekua Bay. Michael, a beekeeper, owns the Hawaiian Queen Company which exports queen bees and makes its own single-source varietal Royal Hawaiian honeys. His daughter, Rebeca Krones, created Tropical Traders Specialty Foods in Oakland, California, along with her partner Luis Zevallos to sell her father’s honeys, and she’s busier than her dad’s bees. “Our bees are constantly foraging as Hawaii has no winter so we get much more honey per hive than the mainland.”

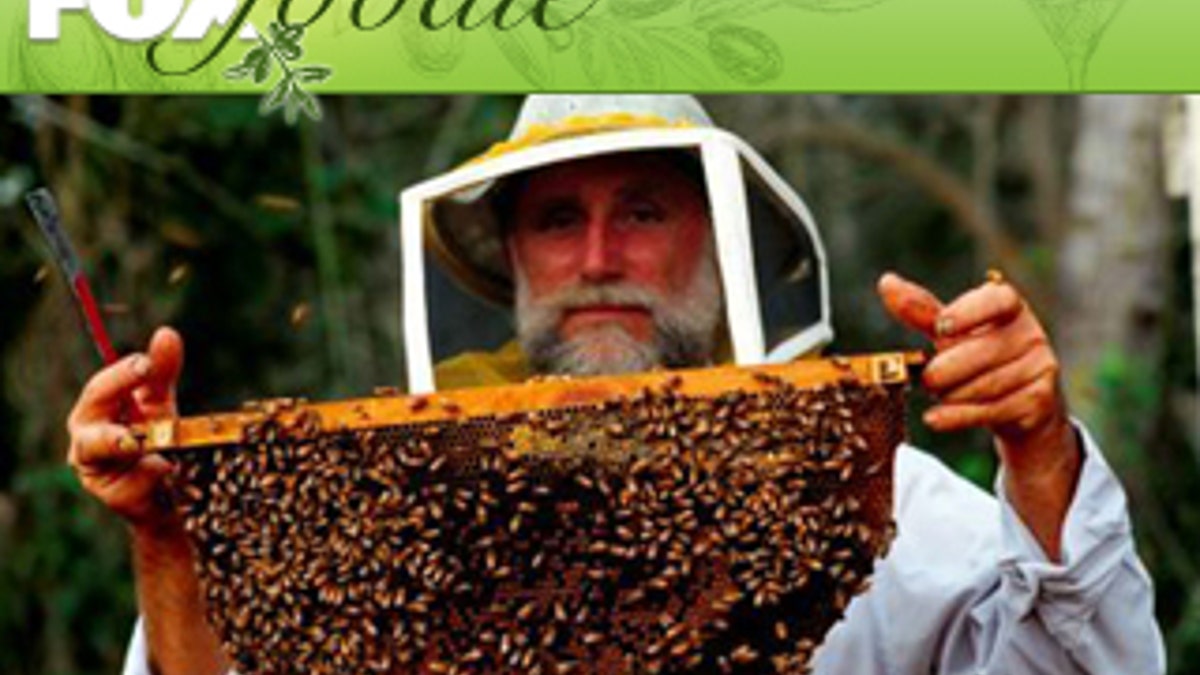

Bees produce honey from the nectar they get from flowers, and one of Michael’s main jobs is to move his hives into a “flow,” the optimal time for bees to forage a particular flower. For example, when the Lehua blooms, Krones moves his hives into the “Lehua flow,” and the health of the little buggers is of utmost concern.

“Bees can fly up to two miles to forage but it wears their wings out and they die,” says Rebeca. “My father controls the areas they forage and the distances they go.” Krones flatbeds his 1500 hives (each is the size of a two-drawer filing cabinet, holds eight to ten frames and houses 50,000 to 60,000 bees) to the three flows that make up his honey. He drives after dark because bees stay in the hive at night. Rebeca and Luis travel to Hawaii three times a year for one-month stints to help her father harvest from “hive to bottle.”

In the world of wine, a “varietal” is one made principally from one grape and carries the name of that grape. It’s the same in the world of honey. Royal Hawaiian’s single source varietals are made from Lehua, a flower species native only to Hawaii, Macadamia Nut Blossom and Christmas Berry. Each is organic and raw. “Lehua’s our best-seller. It has a delicious butterscotch tone to it,” says Rebeca.

Krones used to sell to honey packers on the mainland who indiscriminately mix honeys and process it. Rebeca realized that her father could capitalize on the market for premium honey, a potentially profitable micro-niche market. “We decided to focus on the flavors, flavors that are unique not just to Hawaii but to the region my dad lives in.” And they went organic, a more arduous process than it sounds.

Everything in a bee’s two-mile foraging radius has to be organic for its honey to be certified organic. Most beekeepers live too close to cities and towns or to agricultural areas that have herbicides or pesticides, says Rebeca. “Our foraging sources are pristine. I mean we’re on an archipelago in the middle of the ocean and we’re in one of the most isolated areas on the Big Island.”

If past is prologue, then the path to such a particular profession in such a singular place seems pre-ordained. Her Argentine father and suburban New Jersey mother met while he was beekeeping in Costa Rica and she was in the Peace Corps. They settled in the Bay Area. Her parents bought a 50-foot sailboat when she was a teen and the family sailed down to Cabo San Lucas and moored in the Sea of Cortez for a few months. They sailed onto Hawaii and found a honey farm for sale. “We sold the house to buy the boat and we sold the boat to buy the farm,” says Rebecca.

To make honey, bees, which live only about 35 days, store nectar in a special sack in their abdomens, separate from their stomachs. A full sack weighs as much as the bee. (Unlike the “fighter jocks” in the animated film “Bee Story,” all foragers are female.) Their bodily enzymes break down the nectar’s sugars and begin its transformation into honey. They return to the hive and regurgitate the honey into “nurse bees” or spread it across the honeycomb to let its moisture evaporate, thickening it. Then they fan it with their wings to dry it further. Once it reaches the right viscosity they seal off the honey by capping each honeycomb cell with a wax plug. They eat it when food is scarce consuming from 120 and 200 pounds each year.

Honey packers blend and heat honey for processing. “Heated honey pours like water which makes it easy,” says Rebeca, “but heating destroys the natural enzymes and affects flavor.” Next the honey is ultra-filtered by forcing it under pressure through a fine mesh to ensure that it won’t crystallize. Royal Hawaiian honey is raw meaning it’s never heated and its enzymes are intact. “Crystals are a natural part of honey,” Rebeca says.

The Kroneses harvest their honey by lifting out each frame and slicing off a thin layer of honeycomb, uncapping the bees’ wax plugs. Once uncapped, they put the frames into a centrifuge that spins out the honey “like the spin cycle on a washing machine,” she explains. After it’s spun out they decant it, letting the wax bits float to the top. They strain it through stainless steel mesh filters and bottle it.

Royal Hawaiian Honey is available in several Costcos in Hawaii. “They were interested in selling a native Hawaiian product, not shipped from the mainland,” she explains. “Ours is a high quality, organic raw product,” that is also doing well at Costco as well as Whole Foods on the mainland. “These days people want to know where their food is coming from and they want to know what’s behind the label, and that’s a trend that helps us,” says Rebeca.