Before the first lunch lady ever plopped a gelatinous brown mass onto a compartmentalized plastic tray, children pretty much had to fend for themselves when it came to the midday meal, and were lucky if they got enough to eat. Nowadays, the problem is that kids are obese and unhealthy partly because of what they’re eating at school.

How did we get from there to here?

1. A Fine Pickle

(Library of Congress)

In the 19th century, there simply was no such a thing as a school lunch (unless it was an act of charity). Children either went home for lunch, went hungry, or were given a penny by their parents to buy food. (These high-school girls having a picnic in Pelham Bay Park in New York in 1911 were obviously among the lucky ones.) Streets run amok with penny-wielding kids led at one point to a moral panic about what they were eating—and it wasn't candy, notes Culinary Institute of America food anthropologist Willa Zhen: "Poor kids were using their pennies to buy pickles, which were considered the addictive, terrible junk food of the time, and people were debating how to keep them away from kids."

2. Do-Gooders Step In

A Home Demonstration agent shows mothers of the Food-for-Health club how to pack a nutritious school lunch in Rappahannock County, Virginia in 1932. Photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration. (U.S. National Archives)

By the 1920s, however, Americans had become entranced by the relatively fledgling science of nutrition and home economics, says Susan Levine, director of the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of the greatly informative School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America's Favorite Welfare Program. Lunchrooms became a standard part of school architecture, schoolchildren were weighed and measured for signs of malnutrition, home economists lectured about what to cook and eat (the pupils in this 1933 were Tennessee mothers), and activists argued that "the right kind of food" would help assimilate waves of immigrant children who needed to be turned into "proper Americans." Most school-lunch programs were still volunteer efforts, however.

3. Shirley Temple Likes Milk

A milk carton, apple and lunchbox. (iStock)

Soon after they became commonplace, school cafeterias became yet another place for schoolchildren (like these 1936 young 'uns) to absorb lessons—or propaganda, depending on who you're asking. Kids are still being exposed to it. "They traditionally would hang posters and homemade slogans that were very didactic about food and nutrition," Levine says. "Then, by the '60s and '70s, the food-service companies and corporate brands would send their posters to schools, and they'd put those up on cafeteria walls so that the brands were visible. Eventually school nutritionists sued."

4. A Great Hunger

(Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland Department, Photograph Collection)

During the Great Depression, those volunteer programs couldn't handle the influx of children who now relied on school lunches as their major source of sustenance, like these undernourished Maryland school kids in 1935. Meanwhile, farmers across what was still a largely agricultural country were struggling, and the federal government feared the economy would implode.

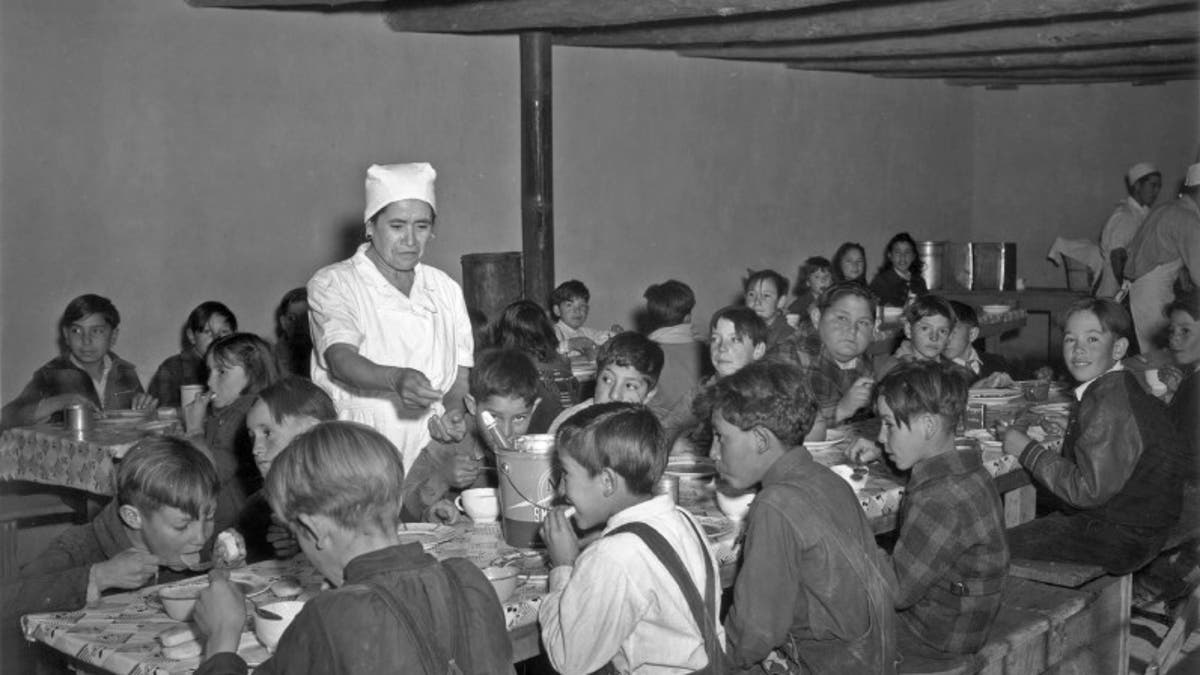

5. Two Birds

The hot lunch, school at Penasco. Childred pay about once cent daily for this hot meal made up primarily of food from the surpus commodities program, and prepared by WPA paid cooks December 1941 in Taos Co, NM. (USDA)

Economists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture hit upon an elegant solution that would serve two purposes: The government would pay farmers for their surplus foods, then donate that food to needy schools to use. In 1933, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act, one of the core pieces of legislation of the New Deal, and, for good or ill, paving the way for the school lunch as we know it today. In this photo, needy kids in Taos, NM, are still eating thanks to the surplus-commodities program in 1941.

6. Surplus Stores

Supermarket (iStock)

The problems with relying on a vast bureaucracy to turn surplus commodities into school lunches quickly became obvious. Among the most ludicrous was the fact that schools got whatever foods farmers had to get rid of lots of, which led to situations where school officials had to make hundreds of children's school lunches out of nothing but onions or olives or grapefruit. It was becoming clear, Levine says, that for the USDA, feeding schoolchildren healthy meals was secondary to keeping farmers afloat.

7. Lunch with Mickey

(Bonhams.com)

The government and activists weren't the only ones who saw a future in getting involved in what kids were eating. In 1935, the very first themed lunch box was released, and it had Walt Disney's seven-year-old star, Mickey Mouse, on it, grinning as he carried his schoolbooks.

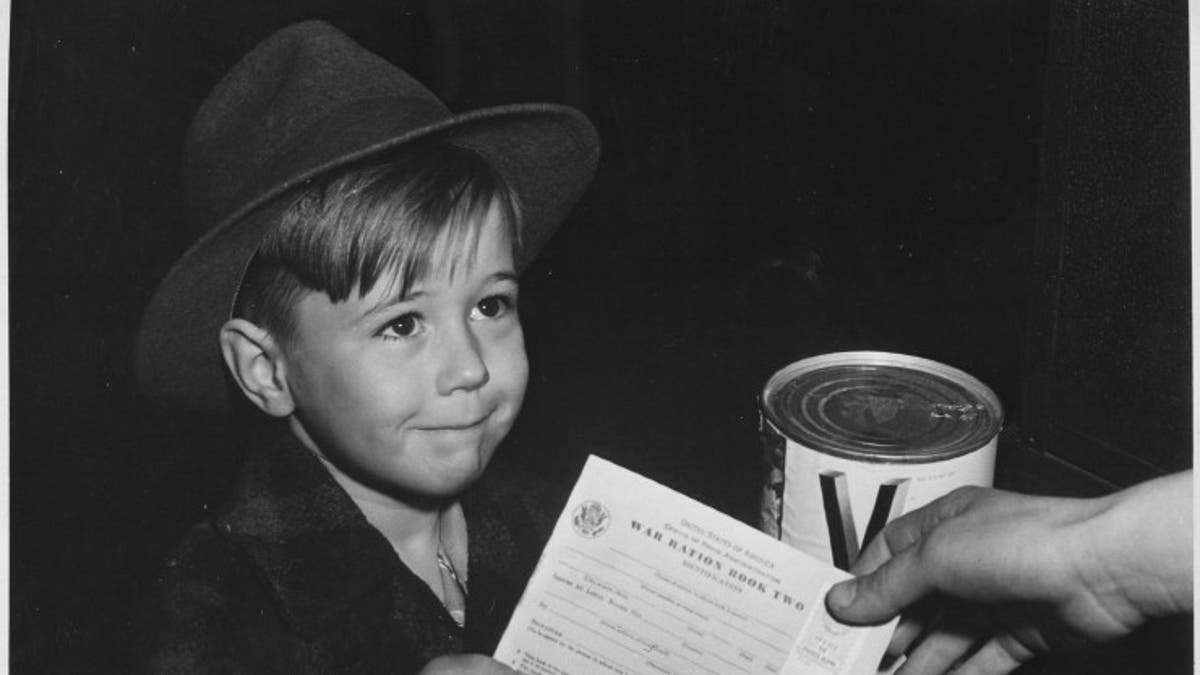

8. The Home Front

Landscape (U.S. National Archives)

As the U.S. prepared to enter World War II, the entire country had to re-engineer itself for war—and many saw an opportunity to re-engineer children's eating habits, as well. As FDR observed, "food and nutrition would be at least as important as metals and munitions." This kid learning about ration coupons in 1943 knew that, too.

Hungry for more information on school lunch history? Read on.

More from Bon Appetit

Avoid These School Lunch Common Mistakes and Pack the Best Brown Bag Ever

19 School Lunch Ideas That Are Healthy (Mostly)

Back to School Recipes, Tested on Real Kids

The Best Ultimate Classic Perfect Recipes (We're Not Joking)