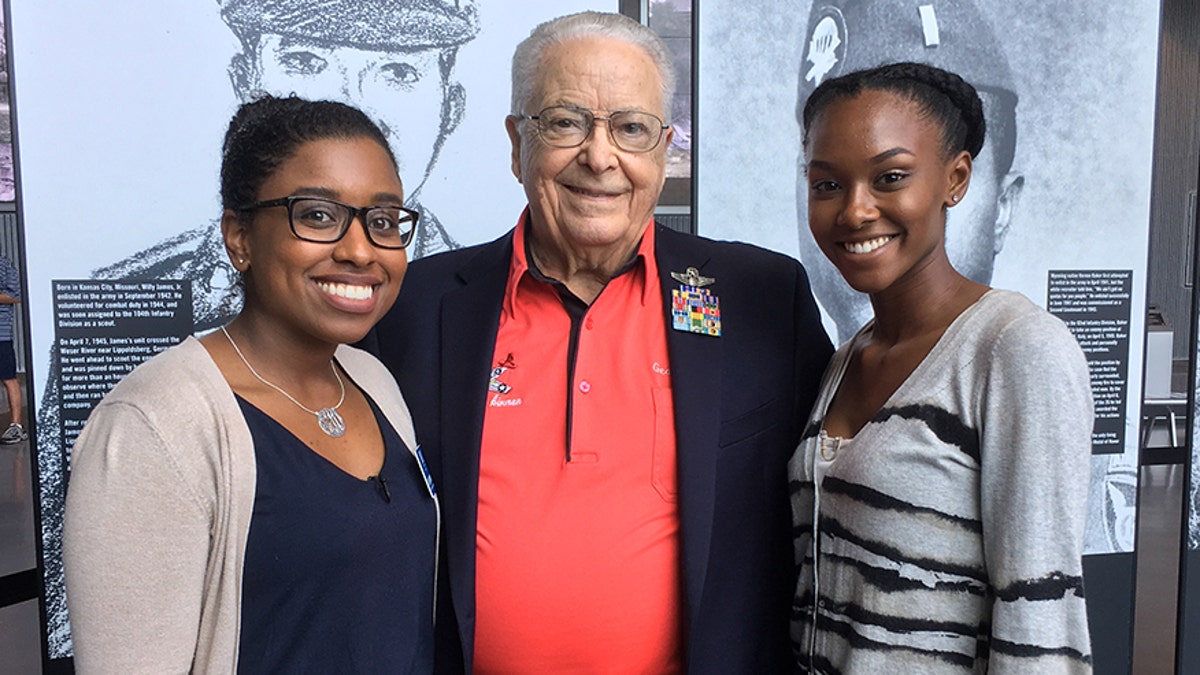

George Hardy, a Tuskegee airman, flew 21 World War II combat missions in the spring of 1945. (Courtesy National World War II Museum)

Up in the air, their skin color didn’t matter.

In the 21 combat missions that Tuskegee airman George Hardy flew during World War II, firing at “trucks, trains, [and] anything to keep Germans from moving supplies around,” the American pilots came together.

“When we were flying, there was no difference,” Hardy told Fox News.

But back on the ground, racial tensions had remained a hurdle for black service members, and Hardy is set to share that experience with younger generations Thursday during a free “electronic field trip” the National World War II Museum is arranging for classrooms across the U.S.

“Race was always a problem. We were originally segregated,” Hardy said. “Everywhere went, we were segregated.”

The live event aimed at middle and high school students, will feature World War II survivors and experts who will “analyze war-era racial injustices, examine artifacts from the museum’s collections and explore WWII historic sites in order to share stories of struggle, setbacks, triumphs and heroism of individuals who changed history,” according to the museum.

George Hardy today with Shelbie Johnson, Family Programs & Outreach Coordinator with the National WWII Museum, and student reporter Mizani Ball. (Courtesy National World War II Museum)

The Black History Month program will include dispatches from student reporters in California and New Orleans, and interviews with Hardy and Betty Reid Soskin, a World War II home front worker and the oldest living National Park Service Ranger.

It will also feature looks at the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park and the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial – the site of the worst home front disaster of the war, in which 320 men, mostly black, were killed in a munitions explosion.

“I think we look back today on that event and we see workers trying to point us to very dangerous conditions that could have been rectified,” Rob Citino, a senior historian at the National World War II Museum, told Fox News.

“Central to the Field Trip’s discussion is an examination of how throughout World War II, African Americans pursued a double victory – one over the Axis abroad and the other over discrimination at home,” the museum said in a statement. “Major cultural, social and economic shifts amid a global conflict were changing American lives.”

Hardy, now 92 and living in Sarasota, Fla., told Fox News that he originally wanted to be an engineer after high school but got drawn into the armed forces as the war heated up.

“The war came along and all my buddies were joining up and I felt I wanted to go, too,” he said. “My older brother was in the service in 1941 and I wanted to go in also.”

“German POWs were able to do things that black and African American citizens were not permitted to do.”

Hardy’s first choice was the Navy, but his father felt it was too segregated at the time and not a good use of his education, as his brother was “only allowed to be a cook.”

He then determined he wanted to fly and started training to be a part of the Tuskegee airmen – the famous black American aviators – as an 18-year-old in December 1943. He graduated the next year and was on his way to Europe.

Hardy said he make the trek across the Atlantic on a small ship with about 400 people, around 23 of which were from Tuskegee.

“Most of the people slept in hull of the ship on these hammocks, but they had to segregate us,” Hardy said of the journey. But this time, he and the other black servicemen were placed in two cabins higher up in the ship and things “worked out in our favor.

“It’s like we went first class and everyone else went in the hull,” Hardy said.

Back at home, black Americans faced segregation and discrimination compared to German prisoners of war, who were sent to dozens of camps in states like Texas. Some of the prisoners traveled to those facilities in luxury Pullman railroad cars while being waited on by black servants, Citino said, in addition to being allowed to visit white-only shops and eat at white-only cafeterias and restaurants.

“In the south, it was not unheard of for black MPs in buses filled with German POWs to move to the back of the bus, while the German prisoners were able to choose their seats,” Citino told Fox News. “German POWs were able to do things that black and African American citizens were not permitted to do.”

President Harry Truman signed an executive order that desegregated the armed forces in 1948, following the conclusion of World War II, which “set a process… that would culminate in big civil rights movements of 50s and 60s,” Citino said.

Citino said the goal of the program is to let students hear alternative voices talking about the World War II experience.

“There have been certain voices that have been largely unheard,” he said.

For more information, click here.