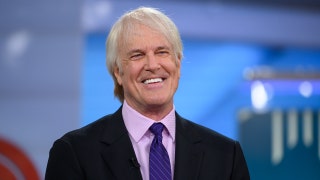

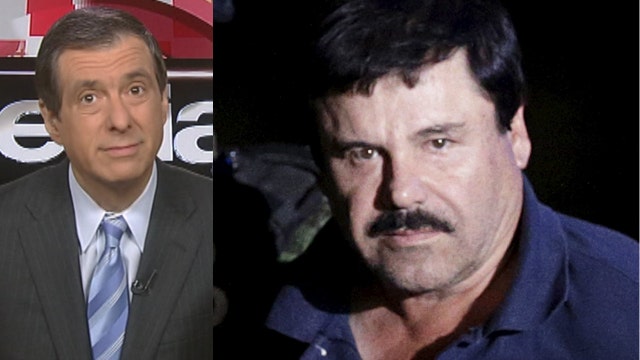

Kurtz: El Chapo, Jann Wenner's latest fiasco

'Media Buzz' host calls Sean Penn's 'Rolling Stone' interview with El Chapo 'an outrage'

When the explosive news hit that Sean Penn had interviewed El Chapo for Rolling Stone, I saw not a hint of skepticism in the New York Times or Washington Post.

In a tsunami of column inches, these and other media outlets appeared unperturbed that the actor had huddled with one of the world’s most notorious fugitives—and given him veto power over the article.

The Times came back with a second-day piece yesterday, but its subdued formulation—“questions have been raised about the ethics for the magazine in dealing with Mr. Guzmán”—seemed obligatory, with the requisite experts quoted on both sides.

More striking was the oblivious stance of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner, who seemed more concerned with shielding the international narcotics king than with the ethical quandaries involved.

“I was worried that I did not want to provide the details that would be responsible for his capture,” Wenner told the Times. “We were very conscientious on our end and on Sean’s end, keeping it quiet, using a separate protected part of our server for emails.” He added that “we would have done everything that a traditional journalism operation would have done in terms of protecting sources.”

So El Chapo was a “source” to be protected by the left-wing magazine.

Ironically, some news organizations say that the secret meeting did lead to El Chapo’s capture last week by providing Mexican authorities with clues to his whereabouts. Pity.

(Times Editor Dean Baquet, to his credit, said he would have walked away from the interview rather than provide pre-approval.)

The Post provided a far more valuable perspective in its second attempt. The paper talked to Alfredo Corchado, longtime Mexico City bureau chief for the Dallas Morning News, who noted the brutal tone of drug violence across Mexico—and how threats have silenced independent media in large swaths of the country.

More than 60 Mexican journalists have been killed or have disappeared over the last decade, the Committee to Protect Journalists says.

“When you’re not really challenging the person and have agreed to submit the story for approval, it sounds more like a Hollywood entertainment,” Corchado told the Post. “It’s not on par with the sacrifice of many of my colleagues in Mexico and throughout the world who have lost their lives fighting censorship.”

But Wenner seems to view the concept as quaint. He didn’t find the granting of advance approval “meaningful,” he says, because “we have let people in the past approve their quotes in interviews.”

So what’s the big deal, since we do it for rock stars? And for Rolling Stone, El Chapo is kind of a rock star.

And here is Penn’s less-than-expansive response to such questions from the AP: “I’ve got nothin’ to hide.”

Given the price paid for access, what did we learn from Penn’s remarkably self-indulgent, 10,000-word piece, much of which was about Sean Penn?

Look at his description of El Chapo: An “almost mythic figure.” A “humble” person. A “Robin Hood-like figure who provided much-needed services in the Sinaloa mountains.” A “figure entrenched in American folklore.”

Yes, he is “a cold pragmatist known to deliver a single shot to the head for any mistakes made in a shipment.” But that’s business, right?

Penn also says he is “drawn to explore what may be inconsistent with the portrayals our government and media brand upon their declared enemies.”

So Senor Guzman is just the victim of bad PR?

This reminds me, sadly, of what came off as a sympathetic profile when Rolling Stone put one of the Boston bombers on its cover. And it comes as the magazine is trying to erase the indelible stain of having accused members of a University of Virginia fraternity of a horrifying gang rape that never took place—and still employs the reporter who wrote it.

I don’t have a problem with journalists interviewing bad guys. If Penn had talked to El Chapo while he was behind bars, fine. But he had busted out of a Mexican prison for the second time. He is not merely alleged to have run a global narcotics business, he was convicted of these crimes.

What this piece amounted to is a successful attempt by El Chapo to soften his image as a ruthless murderer. He gets to say, largely without challenge, that he only uses violence when he is attacked.

In the end, the actor and author finds a way to blame America and its drug users:

“Are we saying that what's systemic in our culture, and out of our direct hands and view, shares no moral equivalency to those abominations that may rival narco assassinations in Juarez?”

The scourge of narcotics and drug violence and murdered journalists isn’t El Chapo’s fault, you see. It’s our fault.