BURLINGTON, Vt. – Vermont prosecutors are forging ahead with a murder case against a woman accused of killing her Alzheimer's disease-afflicted mother and then burning the body, even though the remains were never found and there were no eyewitnesses to the killing.

At issue: Whether there's enough circumstantial evidence to convict Jeanne Sevigny, who reported 78-year-old Mary Wilcox as a missing person in 2006 but was charged last year in her death after an informant said Wilcox had been killed.

Prosecutors say Sevigny, 60, of Westford, killed her mother because she'd become a burden to the family.

Sevigny says she came upon her mother with a pistol in her hands, and that it went off — killing Wilcox — when she tried to take it away. The gun believed to have been used was recovered by police.

She's charged with second-degree murder and faces 20 years to life in prison if convicted. She has pleaded not guilty, and is free on $1.5 million bond.

Her son, Greg Sevigny, allegedly buried a suitcase containing the remains behind an elementary school in Westford. But searches by the Vermont State Police have failed to find it.

A judge last week dismissed the charge against Greg Sevigny, who'd been accused of unlawful disposal of a body, a misdemeanor.

"They're imputing what was an accident into a homicide," said defense attorney John St. Francis, who represents Jeanne Sevigny.

He told a judge Tuesday that a forensic psychologist who examined Sevigny will testify that she freaked out after the gun went off and was insane when she decided to burn the body in a backyard fire pit.

The testimony is aimed at blunting the state's contention that Sevigny's actions after Wilcox's death — burning the body — reflect a guilty conscience, according to St. Francis.

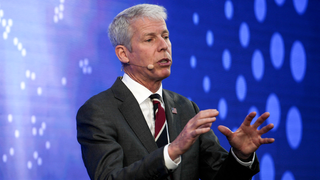

Chittenden County State's Attorney T.J. Donovan said he hopes to put Sevigny on trial, even if the body isn't found.

"It certainly makes our case more difficult, that we haven't been able to locate Mary Wilcox's body," Donovan said outside court. "But we think there's enough circumstantial evidence to bring this case in front of a jury and get it to a jury for them to make a decision."

Criminal law expert Michael Cassidy says that under the circumstances, convicting Sevigny is an iffy proposition.

"Without an eyewitness and without the forensic evidence that can come from an autopsy on a body, it's going to be difficult to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt," said Cassidy, a law professor at Boston College and former chief of the Massachusetts attorney general's criminal bureau.

When Wilcox was reported missing, Sevigny told police she'd disappeared after overhearing Sevigny talking about putting her in a nursing home. The family felt "she was getting to be too much," according to Greg Sevigny.

The break in her disappearance came last December, when Greg Sevigny's ex-girlfriend — who had recently obtained a protective order against him — went to police, telling them he told her that his mother had come to his workplace after Wilcox's disappearance with a large plastic case, asking him to dispose of it.

When asked what was inside, Jeanne Sevigny said: "Your grandmother."

On Tuesday, Vermont Superior Court Judge Michael Kupersmith denied a request to let Greg Sevigny move back in with his mother, who was banned from having contact with him after her arrest. The prosecutor in the case, Mary Morrissey, said allowing contact between them would jeopardize the case.

"Greg Sevigny is the most significant civilian witness in the case," she told Kupersmith. "From the state's perspective, allowing him to have unlimited access and contact with his mother, we think really affects the integrity of the case in general."