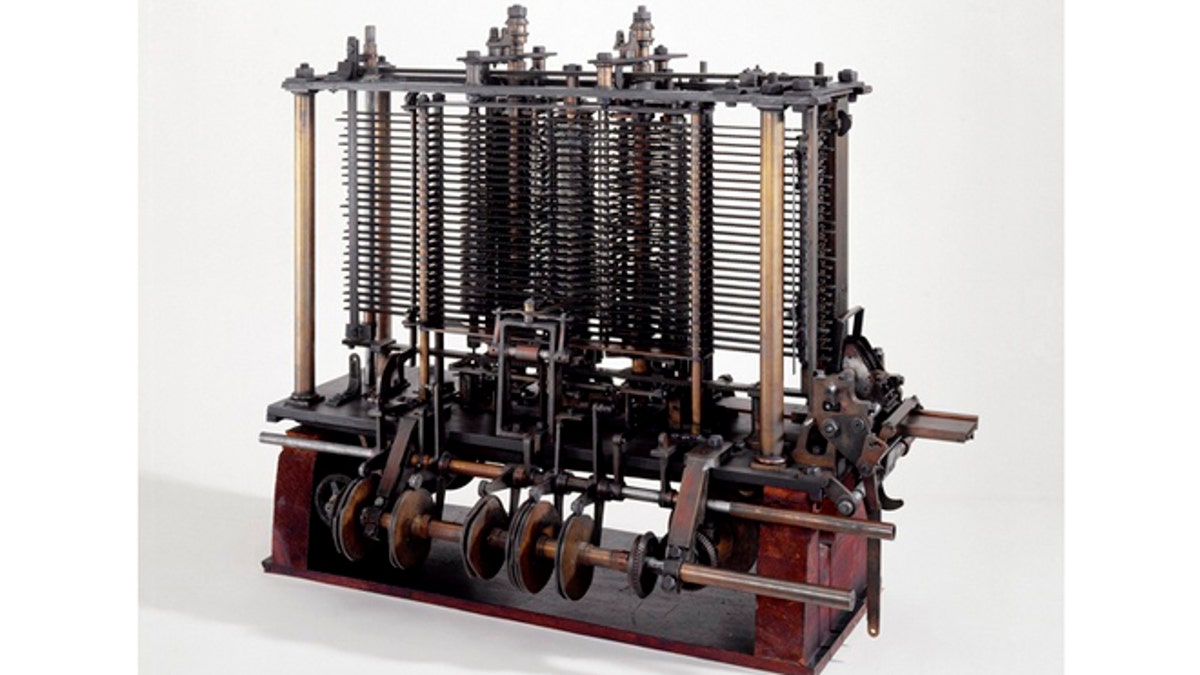

Famed mathematician Charles Babbage designed a Victorian-era computer called the Analytical Engine. This is a portion of the mill with a printing mechanism. (Science Museum)

A Victorian-era device might have jumpstarted the Computer Age more than 100 years before the first personal computers of Bill Gates or Steve Jobs.

That century-old dream has inspired a British programmer to launch a crowd-funding effort that can finally make the steam-powered "Analytical Engine" a reality.

The early computer concept — a brass-and-iron machine the size of a small steam locomotive — came from the mind of Charles Babbage, a famed mathematician who tinkered with different designs for the Analytical Engine until his death in 1871. The Plan 28 project aims to build Babbage's machine by raising $8 million (5 million in British pounds) over the next 10 years.

"The Analytical Engine would have been the world's first computer," said John Graham-Cumming, a programmer and director of Plan 28.

[pullquote]

Victorian-era technology could only do so much. Babbage envisioned a general-purpose computer with just 1 kilobyte of memory — 500,000 times less than the memory of an iPhone 4 — that would have worked 13,000 times slower than the ZX81 home computer made in 1981.

But the Analytical Engine still had the same basic blueprint used by modern digital computers. It had a "Store" for holding numbers and results, a "Mill" for crunching numbers, and could even show its results through devices such as an attached printer. Programs were written in punched cards that represent pieces of stiff paper with holes similar to what some modern voting machines use today.

Such a computer might have changed history at a time when the Industrial Revolution, modern science, new inventions and Imperial British expansion were already reshaping the world. [Top 10 Life-Changing Inventions]

"I think a similar outpouring of ideas would have been generated as we saw when the computer age got started in the 20th century," Graham-Cumming told TechNewsDaily. "The big question is, who would have got to use it; perhaps the military, perhaps the government, perhaps the companies driving the British Empire."

The British government showed early interest in funding one of Babbage's simpler calculating devices, called the Difference Engine No. 1, but cut off funding by 1842. When Babbage died in 1871, none of his machines had been fully built.

One of Babbage's close friends and a fellow mathematician, Ada Lovelace, helped expand on the Analytical Engine's idea while translating a short Italian article about the device. Lovelace's translated article included her own sketches of programs for the machine — earning her the honor of being considered history's first computer programmer.

Modern experts have since built two replicas of Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 on display in London's Science Museum and the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif. The London museum's version helped inspire Graham-Cumming to dare dream of building the Analytical Engine.

"There are literally thousands of pages of hand-written notes left by Babbage and hundreds of large scale plans of the machine," Graham-Cumming explained. "They represent a lifetime of working on the Analytical Engine."

Plan 28 first needs to settle on a single design for the Analytical Engine. A computer simulation could then help test the functionality of the machine before committing to build the huge physical replica.

"Babbage constantly improved his designs and the notes and plans represent a succession of refinements and improvements," Graham-Cumming said. "We think it will take a couple of years to really settle on a plan that Babbage himself would recognize as his machine."

- Ten Computers That Changed the World

- Why Tesla's Wizardry Is Perfect for Hollywood

- 10 Profound Innovations Ahead

Copyright 2012 TechNewsDaily, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.