A pit bull seized from a home in Tecumseh, Neb., in a multistate dogfighting raid July 10, 2009, is seen at the Nebraska Humane Society in Omaha. (AP Photo)

Animal abusers would be tracked like sex offenders if California lawmakers have their way.

The state Legislature is considering a new proposal to establish a registry of names -- similar to widely used sex offender databases -- to track and make public the identities of people convicted of felony animal abuse.

The registry, which under the law would be posted on the Internet, wouldn't just include names. The bill calls for photographs, home addresses, physical descriptions, criminal histories, known aliases and other details to be made public.

Supporters say it's a way to notify communities and local police that animal abusers are living among them and to warn shelters to watch out for them if they try to adopt.

"In part, it's an attempt to give law enforcement a heads up when people like this are in their communities, so they can cut off problems at the pass," said Lisa Franzetta, spokeswoman for the Animal Legal Defense Fund, which is leading a national campaign to get states to establish the registries.

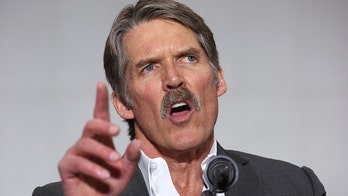

California Senate Majority Leader Dean Florez, who introduced the bill last month, was the first to take a crack at it, though Tennessee has considered something similar. Franzetta said lawmakers from six states have contacted the group to express interest in launching animal abuser databases.

Florez said the bill, which if passed would be the first of its kind, falls in line with other animal protection bills California has pursued. He said the registry is aimed at helping animal control officers do their jobs and animal shelters make sure abusers "don't walk out with an animal they can torture."

But not everybody in California, which also maintains a database of arsonists, thinks a brand new public database of unsavory persons is what the state needs, particularly given its budget troubles.

The tool is estimated to cost between $500,000 and $1 million to launch, and to pay for it, the bill calls for both fines on animal abusers and a new tax on pet food -- in the neighborhood of a few cents per pound. That doesn't sit well with the pet food lobby, since it argues the tax punishes the very people who are trying to help, not hurt, their animal friends.

"We generally don't think that this is a very good proposal," said Ed Rod, vice president of government affairs for the American Pet Products Associations, though he called the idea a worthy goal.

"Making one group of people, the pet owners, pay for something that's going to benefit everyone doesn't seem fair," Rod said. "It's not pet owners in general who are abusing the animals. They're trying to take care of the animals."

The Fresno Bee published an editorial in opposition to the bill Friday, saying the new "state bureaucracy" would be funded by an "unfair tax" on pet owners.

"We also question the registry's effectiveness. We would rather see the penalties and fines substantially increased on those convicted of animal cruelty," the paper wrote. "We have no problem with private groups creating registries. ... But we oppose another state bureaucracy."

Florez, though, said that once launched, the registry would probably only have one employee attached to it and an annual cost of $60,000 to $70,000.

"We don't see this moving into some kind of large bureaucracy," he said.

Franzetta said that the database would only be to flag the worst offenders, like people who hoard hundreds of animals under poor conditions or "sadistic animal torturers" who pick up their prey at shelters. She said recidivism for felony offenders is high and that animal abuse can be a gateway to more egregious crimes -- she said communities should know "who's living among them" just like they can with sex offenders.

"The same logic applies," she said.