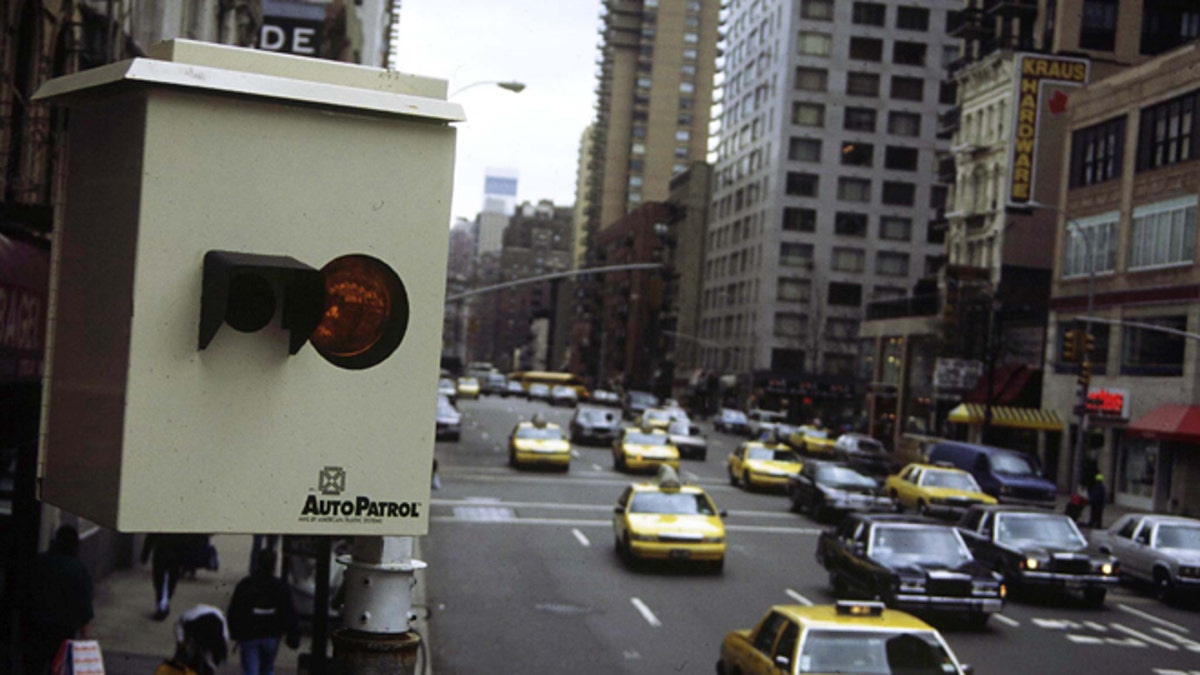

FILE: Undated: A red light camera above a city street in the United States. (REUTERS)

Law enforcement agencies across the United States are using automatic scanners to amass millions of digital records on the location and movement of vehicles, according to a study published Wednesday by the American Civil Liberties Union.

The scanners – which can be affixed to police cars, bridges or buildings -- capture images of moving or parked vehicles that include such details as location and license plate numbers.

The images are then uploaded into police databases and kept for weeks or sometimes indefinitely.

While the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that a judge's approval is needed to track a car with GPS, the ACLU says the image scanning raises concerns about government possibly over-intruding in the lives of everyday citizens.

"There's just a fundamental question of whether we're going to live in a society where these dragnet surveillance systems become routine," said Catherine Crump, a staff attorney with the ACLU, which wants police departments to immediately delete records of cars not linked to a crime.

Law enforcement officials said the scanners can be crucial to tracking suspicious cars, aiding drug busts and finding abducted children.

License plate scanners also can be efficient. The state of Maryland told the ACLU that troopers could "maintain a normal patrol stance" while capturing up to 7,000 license plate images in a single eight-hour shift.

"At a time of fiscal and budget constraints, we need better assistance for law enforcement," said Harvey Eisenberg, chief of the national security section and assistant U.S. attorney in Maryland.

The ACLU found that only five states have laws governing license plate readers. New Hampshire, for example, bans the technology except in narrow circumstances, while Maine and Arkansas limit how long plate information can be stored.

The report comes amid a national debate about the federal government collecting information on Americans’ phone calls and Internet activities – punctuated Wednesday by a heated Capitol Hill exchange over the matter.

The larger debate started when CIA contract worker Edward Snowden revealed, through news agencies, that the National Security Agency had collected such data as part of its anti-terrorism efforts.

Members of Congress said Wednesday that they never intended to allow the NSA to sweep up millions of records.

The most intense moments came when Rep. James Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., told Deputy Attorney General James Cole that Congress only meant to authorize seizures of information directly relevant to national security investigations.

As Cole explained why that was necessary, Sensenbrenner cut him off and reminded him that his surveillance authority expires in 2015.

"And unless you realize you've got a problem," Sensenbrenner said, "that is not going to be renewed."

The Mesquite Police Department, in Texas, has vehicle records stretching back to 2008, though the city plans to begin deleting files older than two years.

"There's no expectation of privacy" for a vehicle driving on a public road or parked in a public place, said Lt. Bill Hedgpeth, a police spokesman. "It's just a vehicle. It's just a license plate."

A spokeswoman for the Metropolitan Police Department, the District of Columbia’s police force, which takes pictures of speed and red light violations, told FoxNews.com that officials have not read the report so they have declined to comment about what officials do with the images.

However, the agency’s website states its photo radar system takes photographs only of vehicles that exceed speed limits, but also collects “basic data about the speed of every vehicle that passes through the radar beam.”

The system also targets only “the most serious and dangerous offenders,” according to the site.

In Yonkers, N.Y., just north of the Bronx, police said retaining the information indefinitely helps detectives solve future crimes. In a statement, the department said it uses license plate readers as a "reactive investigative tool" that is only accessed if detectives are looking for a particular vehicle in connection to a crime.

"These plate readers are not intended nor used to follow the movements of members of the public," the department's statement said.

But even if law enforcement officials say they don't want a public location tracking system, the records add up quickly.

In Jersey City, N.J., for example, the population is only 250,000,but the city collected more than 2 million plate images on file. Because the city keeps records for five years, the ACLU estimates that it has some 10 million on file, making it possible for police to plot the movements of most residents depending upon the number and location of the scanners, according to the ACLU.

The ACLU study, based on 26,000 pages of responses from 293 police departments and state agencies across the country, also found that license plate scanners produced a small fraction of "hits," or alerts to police that a suspicious vehicle has been found.

In Maryland, for example, the state reported reading about 29 million plates between January and May of last year. Of that amount, about 60,000 -- or roughly 1 in every 500 license plates -- were suspicious. The No. 1 crime? A suspended or revoked registration, or a violation of the state's emissions inspection program accounted for 97 percent of all alerts.

Eisenberg, the assistant U.S. attorney, said the numbers "fail to show the real qualitative assistance to public safety and law enforcement." He points to the 132 wanted suspects the program helped track. They were a small fraction of the 29 million plates read, but he said tracking those suspects can be critical to keeping an area safe.

Also, he said, Maryland has rules in place restricting access for criminal investigations only. Most records are retained for one year in Maryland, and the state's privacy policies are reviewed by an independent board, Eisenberg noted.

At least in Maryland, "there are checks, and there are balances," he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.