UPDATE TWO: Sen. Graham's spokesman, Kevin Bishop, passed along a set of talking points about the South Carolina Republican's still-developing tax on gasoline, a so-called "linked fee" that would establish a separate tax on a gallon of gas and adjust that tax over time in relation to lower industrial and utility pollution. In theory, as emissions fall, so would the magnitude of the tax on gasoline.

Graham is adamant his energy fee is not a straight gasoline tax, even though critics say by whatever name it will raise the price at the pump and, consequently, harm recession-battered consumers.

The Senate GOP leadership today took pains to say this tax idea is Graham's and Graham's alone. It's not the first time Graham has been out on a policy limb. Graham insists his approach is better than one-size-fits-all federal regulations (The Environmental Protection Agency now has the legal authority to impose regulations reducing green house gas emissions. The agency recently announced it would delay any new for one year to give Congress time to hammer out its own climate change legislation). President Obama has said he prefers congressional action to federal regulation.

Graham's office, via spokesman Kevin Bishop, described the senator's efforts this way:

"Senator Graham does not support a gas tax. And the bill he is working on does not include a gas tax. He is working with the energy industry to protect consumers from a cap-and-trade system which would do great damage to our economy and national security by driving our refiners overseas.

In this effort, he has some simple but important goals.

• Create legislation that will significantly reduce our dependency on foreign sources of oil. Today we are more dependent on foreign oil than we were before 9/11. It is a national imperative that we must break this unhealthy addiction. By importing ever increasing amounts of foreign oil, we are placing our economy and national security at risk.

• Preempt the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) from issuing regulations on greenhouse gas emissions which will do great harm to our economy.

• Create millions of new, 21st Century jobs by ensuring environmental policy is good economic policy.

• Limit carbon pollution.

UPDATE: Confirming earlier reporting in this blog, the White House has now officially announced its opposition to any increase in federal gasoline taxes as part of Senate climate change legislation.

Sen. Lindsay Graham, R-S.C., has advocated higher gasoline taxes in the context of intense and highly complex negotiations to build Republican support for climate change legislation. Graham doesn't call the higher fee - currently proposed as 15 cents per gallon - a straight gasoline tax. Rather, Graham considers it a fee on oil and gas industry pollution.

Graham is working with Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts and Sen. Joe Lieberman, I-Connecticut, to forge a bipartisan consensus on a climate change bill. Those efforts continue. White House opposition to the gas tax all but kills the idea, but the White House statement leaves is vague enough not to rule out entirely some variation of the Graham proposal. Negotiations continue.

Here is the official White House position in a statement from White House spokesman Ben LaBolt.

“The administration is working with Senators Kerry, Lieberman and Graham to move forward bipartisan, comprehensive energy and climate legislation that creates clean energy jobs and reduces our dependence on foreign oil. The Senators don’t support a gas tax, and neither does the White House. The Senators are considering a variety of mechanisms that would foster a transition to a clean energy economy, and we will continue to work with them to identify a means to create a major growth driver for our economy and reduce the pollution that contributes to climate change.”

Original blog post picks up here:

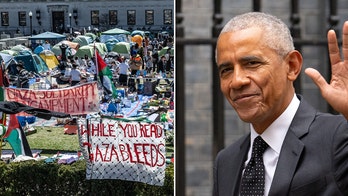

The Obama White House opposes a move in the Senate, led by South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham, to raise federal gasoline taxes within still-developing legislation to reduce green house gas emissions and boost alternative energy supplies, senior administration sources told Fox.

Officially, the stated White House policy, articulated by spokesman Ben LaBolt, is the administration would "review" Graham's proposed 15-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax increase.

But sources told Fox the White House will oppose Graham's gasoline tax gambit because senior advisers believe it has three flaws: it will shield the oil and gas industry from paying to lower green house gas emissions; it will force higher prices on consumers still struggling during the recession; and it will not change driving behavior enough to significantly reduce tail-pipe emissions.

The federal gasoline tax is currently 18.4 cents per gallon.

The Graham plan remain a bit opaque and is the subject of intense talks within GOP ranks. Graham is trying to build Republican support for a climate change and alternative energy bill. To do that, Graham is looking for what his spokesman Kevin Bishop called "sector specific" revenue sources as an alternative to across-the-board taxes on carbon-based pollution under a so-called cap-and-trade system.

"This is still a work in progress," Bishop said of Graham's gasoline tax. "We are in negotiations and nothing has been agreed to."

The concept, Bishop said, is to use a higher gasoline tax to help vehicle tailpipe emissions, which he said account for one-third of all green-house gases. The White House, administration sources tell Fox, already believes it's accomplished that with new, stricter fuel efficiency and tailpipe emissions standards.

While most on Capitol Hill regard Graham's proposal a gasoline tax, that not how it's being legislatively marketed. Graham instead calls his idea a "linked fee."

Why?

Because the tax links the price of the higher gasoline tax to the average cost of emission permits the federal government would give to electric utilities and power plants. The emission permits would allow companies to buy the right to pollute or trade the credits they earn for reducing pollution to other plants or utilities that release more green house gases.

Under Graham's plan, the 15-cent per gallon gasoline tax woud rise alongside the price of the permits purchased by factories and utilities. Similarly, the gasoline tax would fall as the price of those permits decline. It's a complicated formula that Bishop concedes has yet to be fully drafted and yet to win any signifcant Republican support.

Graham's idea has drawn initially favorable reaction from numerous integrated oil and gas companies and may, Bishop said, attract the support of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Oil and gas companies that long-opposed higher gasoline taxes have warmed to one this time as an alternative to what they fear could be higher carbon taxes tied to their refinery operations.

A higher gasoline tax would direct pollution-reduction costs to consumers, not industry. Administration sources say that's the principle reason the White House opposes Graham's idea. Senate Democrats are also unnerved by the idea of imposing higher gasoline taxes - by whatever name - on consumers during the high-cost summer driving season.

There are other complications.

Historically, gasoline taxes have almost always been used to finance the federal Highway Trust Fund (with two exceptions - President George Herbert Walker Bush devoted half of a 5-cent increase in taxes to deficit reduction in 1990 and President Clinton applied a 4.3-cent increase in gasoline taxes to deficit reduction. The Clinton tax was transferred to the Highway Trust Fund in 1997). The trust fund finances road, highway and other transportation construction and repairs.

But Graham's so-called "linked fee" would finance federally backed projects to subsidize alternative energy sources, reduce green house gas emissions, and improve energy conservation. To do that, lawmakers would have to agree to raise gasoline taxes without any benefit to the Highway Trust Fund.

Bishop called this an issue of significant concern to senators and conceded for the linked-fee to work within the trust fund the fund itself would have to be defined and its mission significantly changed.

"We are looking at a fundamentally different approach to the (House) bill," Bishop said. "But it's not easy."