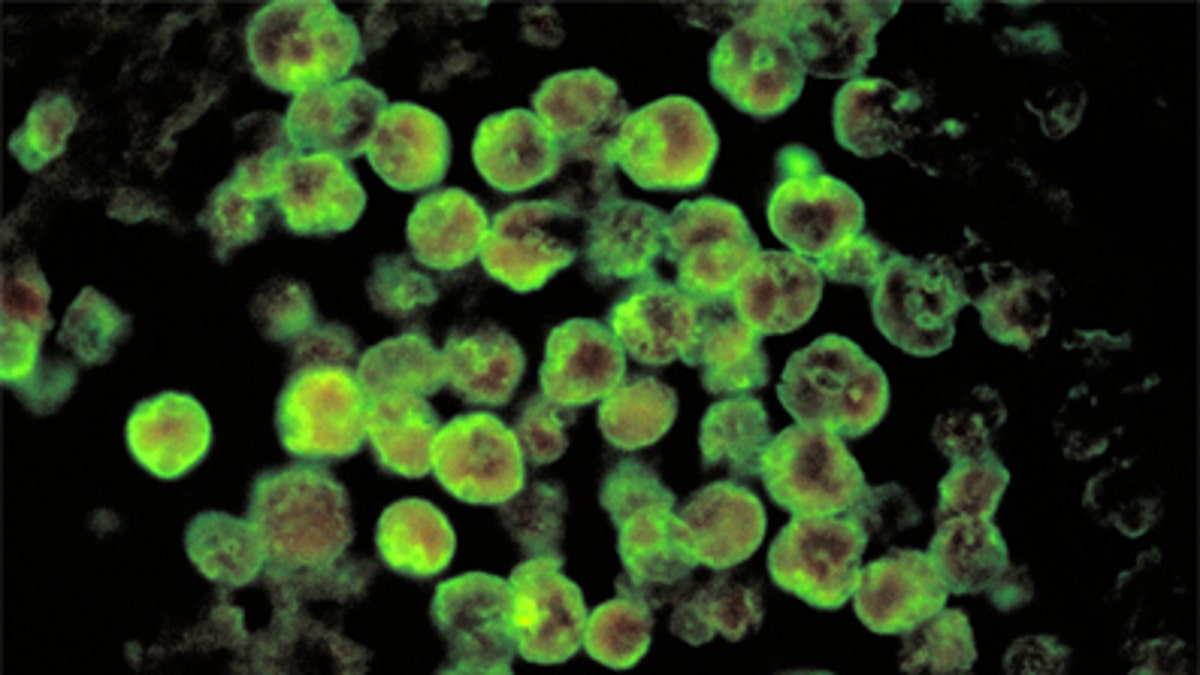

Amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. (CDC/ Dr. Govinda S. Visvesvara)

Following the deaths of two people from Louisiana who contracted brain-eating amoeba infections from their own home water systems last year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are warning people to follow appropriate guidelines when using a popular home remedy for sinus infections.

The victims, a 28-year-old man and a 51-year-old woman from different parts of the state, died from primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) – an almost universally fatal infection – after using neti pots filled with tap water to irrigate their sinuses.

Water samples taken from the victims’ homes tested positive for Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri), a climate-sensitive amoeba found in warm freshwater lakes and rivers. N. fowleri has over a 99 percent fatality rate, with only one known survivor in the U.S. since 1962.

The amoeba enters the body through the nose and migrates through the olfactory nerve to the brain. Symptoms, which occur one to seven days after exposure, include headache, fever, stiff neck, loss of appetite, vomiting, confusion, seizures, coma and death.

In response to the findings, the CDC and FDA are reminding consumers to use boiled, distilled or filtered water when using neti pots or other nasal-rinsing devices.

“Some tap water contains low levels of organisms, such as bacteria and protozoa, including amoebas, which may be safe to swallow because stomach acid kills them,” the FDA said in a released statement. “But these ‘bugs’ can stay alive in nasal passages and cause potentially serious infections.”

First reported infections from tap water

The Louisiana deaths are the first reported PAM cases in the United States associated with treated municipal water, though cases have been reported previously in Australia and Pakistan, and two cases in Arizona in 2002 were linked with untreated well water, according to the CDC.

The organization added that city distribution systems serving the victims’ homes did not test positive for N. fowleri, but rather, the homes’ plumbing.

“What the victims both had in common were they were both regular users of nasal irrigation and used tap water from their homes,” Jonathon Yoder, coordinator of the Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System at the CDC, told FoxNews.com. “We were able to identify [N. fowleri] organisms in the pipes of each of their homes.”

According to Yoder, it is unclear how the amoeba entered the pipes, but once inside, the organisms were able to survive and spread through the hot water system.

Because these were the first U.S. cases of amoeba spreading through disinfected home water supplies, there are no formal recommendations to kill or prevent N. fowleri in this setting. There have been no studies conducted to date looking at the prevalence of amoeba in home water pipes, Yoder said.

However, he stressed that, “it’s not the point of this investigation to say that people should have their water tested [for amoeba] – one of the takeaways is that infection is not associated with general things like drinking water, bathing or showering. It seems to be associated with water directly forced up the nose during irrigation.”

Highly rare – but spreading

Though rare – typically less than 10 cases are reported per year – PAM is frequently associated with swimming in warm, untreated water. The median age of patients is 12 years old, and the majority of infections occur in boys.

“The highest ever amount of reported infections was eight in 1980, and some years no cases are reported at all,” Yoder said. “Certainly, it’s a very rare infection. Unfortunately, for the families of those infected, it’s very tragic because it almost certainly leads to death.”

While N. fowleri is profiled as a warm-weather amoeba found primarily in Southern states, CDC tracking has increasingly found incidences of infection in Northern states as well – expanding its believed geographic range. Recent case reports have detailed infections in Kansas, Virginia and even as far north as Minnesota in 2010.

Yoder speculated the change may be due to prolonged heat waves in Northern regions and advised that physicians and the public at large in those areas be aware of the potential for infection.

“It’s something that physicians in (those) areas should keep in mind, especially during prolonged heat weaves,” Yoder said.