No charges for dentist who killed Cecil the lion

Zimbabwe officials say Walter Palmer had legal authority to hunt

The international backlash against big game hunters triggered by last year's killing of a beloved lion named “Cecil” could spell doom for hundreds of the beasts who now roam a Zimbabwe preserve.

The deafening criticism after Cecil’s death in July has created a chilling effect among many in the industry, leading to more hunters staying home, animal populations growing out of control and a more dangerous environment for guides, say experts.

The death of a lion named Cecil sparked international outrage. (AP)

“Far fewer hunters are going to Zimbabwe,” said Steve Taylor, a former game ranger and current guide in Zimbabwe who is also associate director for International Safety and Security at Harvard University. “Directly after the Cecil situation numbers declined precipitously.”

One Zimbabwean conservancy floated the idea of culling nearly 200 of its lions to fight overpopulation. That notion – since tabled – has drawn condemnation, but it highlights the desperation some conservancies face as lion and other animal populations go unchecked, say some conservationists.

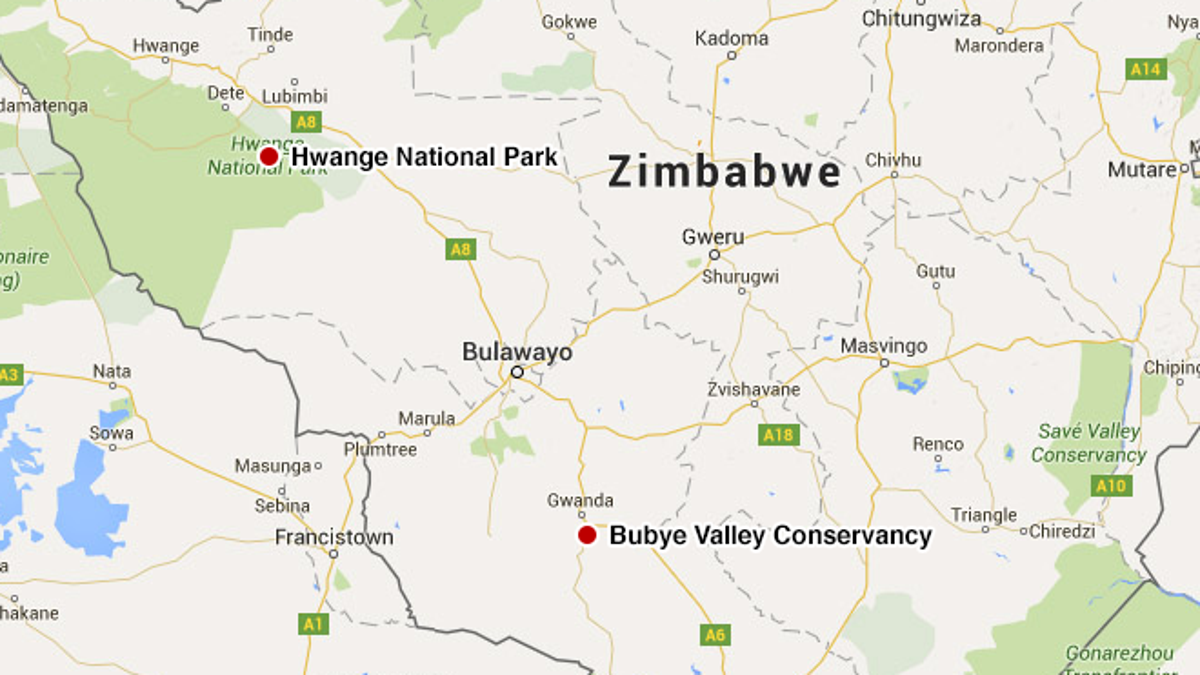

Efforts to move some of the more than 500 lions living in the confines of the Bubye Valley Conservancy have so far been derailed. But the issue of overpopulation received little attention – until the cull proposal was mentioned.

“We were all talking about it: If you shoot a lion, your career’s over.”

“I think this is their way of saying to the naysayers who have denigrated the whole concept of a conservancy, ‘Somebody needs to step up to the plate,’” Taylor told FoxNews.com. “Hunters will not do it anymore. Somebody needs to step up to the plate and finance the translocation of those lions. It’s a great way to grab the media attention.”

A map of Zimbabwe showing the location of the Hwange National Park where Cecil was shot and the Bubye Valley Conservancy.

Minnesota dentist Walter Palmer faced global scorn after he shot and killed Cecil with a compound bow. Palmer was lambasted on social media, had demonstrators protest outside of his office and even faced death threats. But he was never charged with a crime because authorities said he had obtained the legal authority to hunt Cecil.

Bubye, located about 300 miles southeast of the Hwange National Refuge where Cecil was shot, relies on trophy hunting to support its operating costs. But since Cecil’s death – and the outrage that followed – there has been a slowdown of hunters willing to travel to Zimbabwe to bag big game. In addition to negative public opinion impacting decisions, hunters have also been hampered by several major airlines refusing to fly exotic animal trophies and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service listing species of African lions as endangered.

Some have referred to the trend as the “Cecil Effect.”

The Bubye Valley Conservancy has more than 500 lions. (Byron du Preez)

Brent Stapelkamp, a researcher who works at Hwange and studied Cecil, also said he’s heard “many, many hunters” have cancelled trips since Cecil’s death.

“Now, whether that has to do with an awareness that things in the Zimbabwe hunting industry are not right, fear of being exposed on social media, restrictions on getting trophies home or what, we can’t say,” Stapelkamp told FoxNews.com. “But I am sure that there has been a massive cancellation of hunts and the industry is suffering.”

Byron du Preez, the project leader at Bubye, said in an email that linking declining hunts to Cecil’s demise may be an overreach.

“In my opinion, the ‘Cecil Effect’ doesn’t even exist,” he said. “Hunters are not coming because there is a massive recession [in the U.S.].”

But criticism has certainly reached Bubye’s fences, and not only for the cull suggestion. A professional hunter familiar with Bubye attempted to set up a hunting raffle for the conservancy, with 100 tickets each selling for $1,500. The raffle would have provided economic benefits for Bubye as well as helped to thin the lion population. But advocacy groups quickly sounded the alarm and the raffle was cancelled.

And there’s another face of the so-called effect – one that’s far more dangerous for humans.

Less than two months after Cecil’s death, an experienced guide was leading a tour group in Hwange when he was confronted by an aggressive lion named Nxaha and was mauled to death. Taylor speculates the criticism stemming from Cecil’s shooting may have caused the guide to hestitate in defending himself.

“We were all talking about it: If you shoot a lion, your career’s over,” said Taylor, who believes Swales may have been reluctant to shoot the beast for fear of public reprisal. “This guy was a really successful guide, and he died by a lion. And I think that’s the Cecil Effect. Guides in Zimbabwe are petrified of having the world turn on them.”

Taylor said he used to hunt, but hasn’t for more than a decade. Still, he understands the benefits of controlled hunting for the environment. But even Taylor – born in Kenya, raised in Zimbabwe, experienced in the industry – isn’t sure how the nation can change the West’s perception of hunting following Cecil’s death.

“Hunters in America now are even afraid to post photographs on Facebook and social media,” he said. “And with the groundswell of public opinion – how do you combat ignorance?”