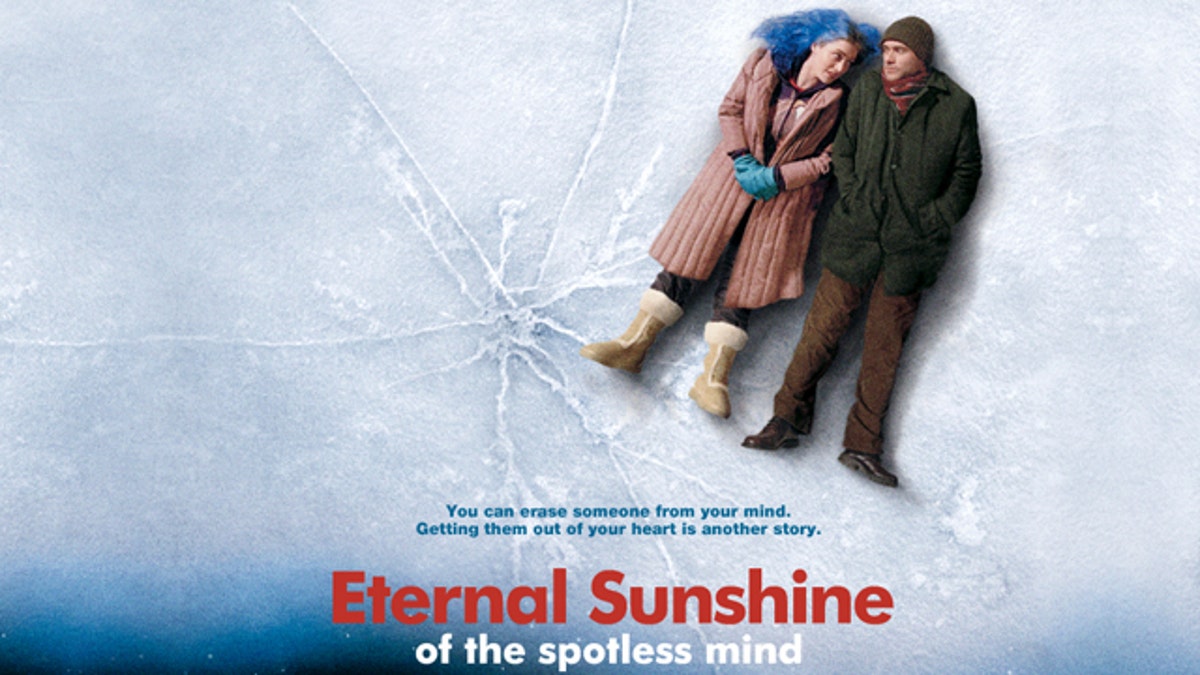

In the film "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind," a couple undergoes a procedure to erase their memories of each other. Scientists are now one step closer to such a scenario. (Focus Features)

What if you could erase your memories? Or restore those you’ve long forgotten?

That’s the premise of the 2004 film "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind." The Jim Carrey movie suggested that, in an alternate reality, doctors could re-program our memories. Drunken binge last weekend? A relationship you’d like to forget? No problem.

It's more real than you might think, thanks to experiments with "memory programming" conducted by researchers at the University of Southern California’s (USC) Viterbi School of Engineering and Wake Forest University’s Department of Physiology and Pharmacology. Their research could lead to breakthroughs in dealing with human memory loss, especially to help the 5 million Americans who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease.

USC researcher Theodore Berger stuck probes in the brains of rats and had them push levers to get a reward. When his team injected a pharmaceutical agent into the rats, they would no longer remember which lever to pull.

Berger studied the hippocampus region in the rat’s brain -- the area that converts short-term memories to long-term memories -- slowing down processing in the CA1 and CA3 regions.

Just as important, the memories came back when the CA1 and CA3 regions were reactivated.

Sam Deadwyler, who led the research team at Wake Forest, told FoxNews.com that the next step is to see if the chemicals used to block memories could work on more complex brain functions.

“We want to see if these same relationships hold for hippocampal processing in more advanced animal species with more complex brain structures,” says Deadwyler.

Deadwyler was hesitant to draw quick conclusions, but suggested they would eventually look at programmable memory in primates.

Dr. Howard Eichenbaum, who directs the cognitive neurobiology lab at Boston University, told FoxNews.com that researchers know human neurons in the brain hold memories in vast clusters. He envisions molecular tags that could be placed on some of those neurons and then tracked. If those memories were lost, doctors could stimulate just those cells to reactivate memories.

That’s a promising scenario, especially for the millions who suffer brain damage and memory loss from a severe car accident or other trauma.

Yet Eichenbaum stopped short of saying the "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" scenario was suddenly going to happen. Memories tend to overlap -- wipe out a bad memory of your first date and you could suddenly forget how to walk or how to drive home.

He said a better approach might be to build a memory-assistance computer chip that works like the human brain, storing memories that can be activated or disabled.

“It’s clear the hippocampus acts like a warehouse manager, storing an array of locations in the cortex where various elements of a memory are held -- and the hippocampus has the ability to reactivate the correct neuronal populations in the correct sequence to recover a memory,” he said.

Interestingly, the process of programming memories is already an established scientific practice.

Dr. Shadi Farhangrazi, a neuroscientist and founder of consulting firm BioTrends, told FoxNews.com that doctors use psychotherapy to deal with traumatic experiences in patients. For example, a soldier coming back from Iraq might be led through a series of memory tasks to help him or her deal with a traumatic event. This “programming” helps organize the neurons in the brain.

Farhangrazi said memory programming could take multiple forms: training exercises combined with drug therapies. Still, she said our understanding of the incredibly complex brain is anything but complete.

“We go through years and decades of learning and relearning, and our memory structure is a lot more complex [than rats],” Farhangrazi said. “However, these studies are a good start if we can eventually help patients who have been suffering from traumatic experiences.”

Berger's paper, published this month in the Journal of Neural Engineering, also suggests a chemical “prosthesis” that could be used in patients to activate lost memories.

John Brandon is a science and technology writer, follow him on Twitter @jmbrandonbb.