NASA, SpaceX set new time for Crew-8 launch

Fox News senior correspondent Jonathan Serrie provides the latest developments as NASA and SpaceX prepare for the launch of the Crew-8 mission.

ATLANTA — There has never been a homicide in space. But Detective Zack Kowalske is conducting research to investigate the first murder in microgravity, not if — but when — it occurs.

"Where humanity goes, so too will human behavior," said Kowalske, a crime scene investigator (CSI) for the police department in Roswell, Georgia, a suburb north of Atlanta. "So, being able to understand how to best reconstruct those criminal acts is really important."

On Earth, CSIs examine blood spatter to determine an attacker’s position in relation to a victim. But Kowalske became curious about how those calculations would change if gravity were removed from the equation.

NASA WELCOMES ITS NEWEST CLASS OF ASTRONAUTS AFTER TWO-YEAR TRAINING IN HOUSTON

He teamed up with researchers at University of Louisville in Kentucky and Staffordshire University and the University of Hull in England to examine spatter patterns created in microgravity. They conducted their research aboard a parabolic aircraft, a plane that goes into a series of steep, controlled descents to create brief periods of weightlessness inside the cabin.

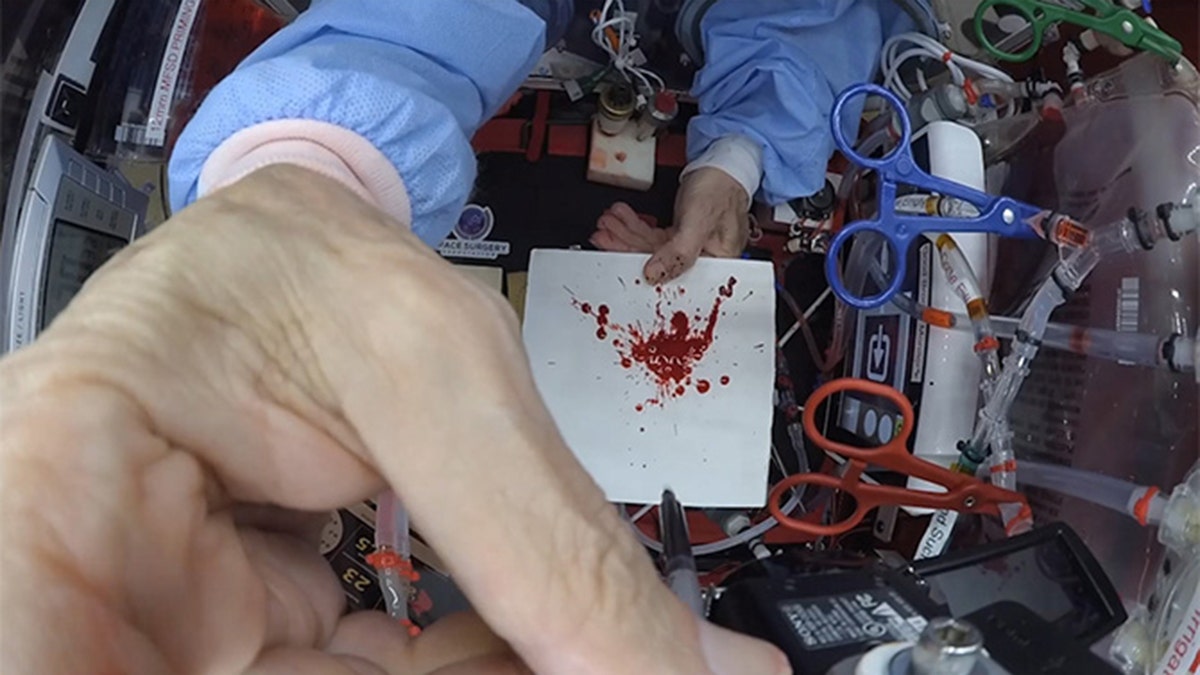

During these "zero gravity" periods, one of the researchers used a syringe to spray simulated blood at a target inside a glovebox resembling a pediatric incubator.

Without gravity’s downward pull, Kowalske and his colleagues knew the simulated blood would follow a straight trajectory. But when it struck the targets, the researchers were surprised to find much smaller spatter patterns than what they would see in normal gravity conditions.

Det. Zack Kowalske holds a sample of simulated blood spatter. (Fox News)

"What happened is when you remove gravity, surface tension becomes the predominant factor," Kowalske said. "So, it actually inhibits the spread of that blood, causing an inaccuracy in your calculation."

The first homicide in space will not only require new investigative procedures, but likely raise questions about who’s in charge of the investigation.

"Jurisdiction will be tricky," space attorney Michelle Hanlon explained to Fox News in an email. "Space objects remain under the jurisdiction and control of the State that launched the object."

US AND JAPAN CALL FOR BAN OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN OUTER SPACE

But that can include the nation that requested the launch in addition to the country owning the territory or facility where the launch took place.

"So, if you have a modular space station run by a Japanese company, whose modules were manufactured in Germany and then launched by the U.S., all of those States may claim jurisdiction," explained Hanlon, who serves as CEO of For All Moonkind, a nonprofit space policy advocacy group. "Of course, the next question is what happens if the crime occurs in an object made in space? Jurisdiction will be even more complex!"

The primary international agreement governing space activities, the Outer Space Treaty, holds nations liable for damages their citizens cause in space. Because of this, Hanlon predicts victims or their survivors will also want a say in who investigates.

While traveling aboard a "reduced-gravity" aircraft, researchers sprayed imitation blood to simulate a crime scene in space. (Zack Kowalske)

Although becoming an astronaut for a government space agency, such as NASA, remains highly selective, Detective Kowalske said the future growth of private "space tourism" increases the risk of a less professional individual causing mayhem in the final frontier. However, his research also has potential applications for accident reconstruction.

"Say hypothetically, we have a ship in orbit and there's a catastrophic event," Kowalske said. "We can use blood stain patterns to reconstruct where crew members were, what positioning they may have been in during the course of that catastrophic failure."

Kowalske and his colleagues have published their study in the journal "Forensic Science International: Reports." For the suburban Georgia detective, it was part of his ongoing PhD research and the culmination of what started as "a crazy idea."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"Research is cool, right? Science is awesome," Kowalske said. "You never know where asking a question is going to lead. But you can find out."