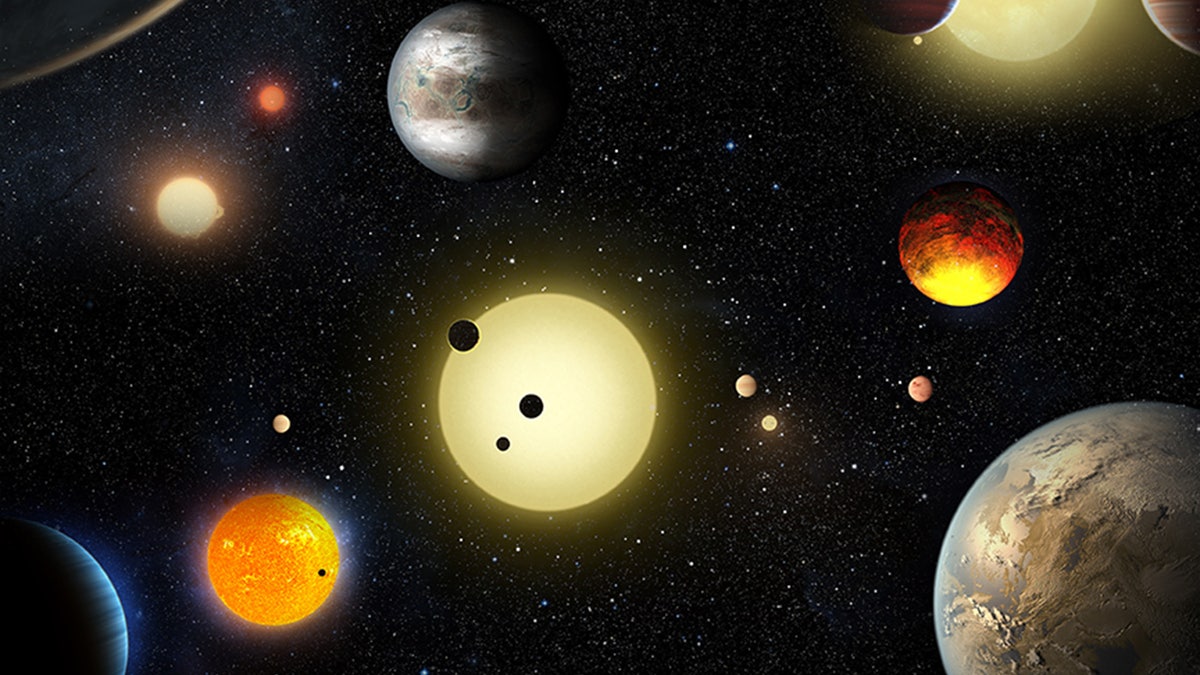

(NASA)

NASA announced today that it had validated the existence of 1,284 new planets in our galaxy that are outside of our solar system— bodies known as exoplanets— and that of those, nine are small planets located in what the space agency calls the “habitable zone.”

This brings to 21 the number of planets that are both littler than twice the size of Earth and also reside in the habitable zone, according to NASA.

The exoplanet data comes from a space telescope called Kepler, which uses the “transit method” to measure the way a star’s light dims slightly when a planet passes in front of it. But this technique requires follow-up observations to make sure that what caused the decrease in starlight was actually a planet, and not an imposter like a brown dwarf star.

Related: NASA releases stunning Mercury transit video

As part of the announcement, Timothy Morton, an associate research scholar at Princeton University, described a method that uses statistics— and not ground-based follow-up observations— to validate whether or not a possible planet is in fact a planet.

“This is the most exoplanets that have ever been announced at one time,” Morton said during the announcement.

The planets are all in the Milky Way, and are "typically hundreds of light years distant" from Earth, Morton said in an email to FoxNews.com.

Related: NASA plane detects atomic oxygen on Mars

Out of a 2015 catalog of 4,302 planetary possibilities discovered by Kepler, NASA said 707 of them are probably imposters. Nine-hundred and eighty-four stars from that catalog had already been validated, 1,327 are “more likely than not” planets, and the remainder are the 1,284 newly-validated planets.

NASA’s ultimate goal with this kind of research is to figure out whether or not humans have company in the universe.

"Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy. Thanks to Kepler and the research community, we now know there could be more planets than stars,” Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement. "This knowledge informs the future missions that are needed to take us ever-closer to finding out whether we are alone in the universe."