U.S. Classmates Rally For Leopoldo Lopez

Kenyon College classmates rally support for Venezuela's opposition leader, Leopoldo Lopez.

It was 1989 in Gambier, Ohio – on a quaint campus flanked by cornfields and rolling hills.

A dashing, confident freshman from Venezuela was spinning visions before a group of fellow students at Kenyon College – a small private liberal arts school – about forming an organization that would raise awareness about social and environmental causes.

Leopoldo Lopez’s idea became a reality. In no time, the organization, Active Students Helping the Earth Survive, or ASHES, became one of the best known and most popular groups on the campus of some 1,600 students.

“It was a sign of someone who knew how to build something. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Leopoldo became the social conscience of the campus,” recalled Rob Gluck, a Kenyon classmate of Lopez’s.

To see this unjust illegal imprisonment at the hands of the [Nicolas] Maduro government, it just moved all of us to act.

Lopez returned to Venezuela after getting a master’s degree at Harvard University, as he always said he would. There, harnessing the galvanizing talent he showed as a student in the United States, he became a leader of the opposition to the socialist government of President Nicolas Maduro, spearheading street protests in mid-February that drew thousands in Caracas.

WATCH: Going to School With Leopoldo Lopez

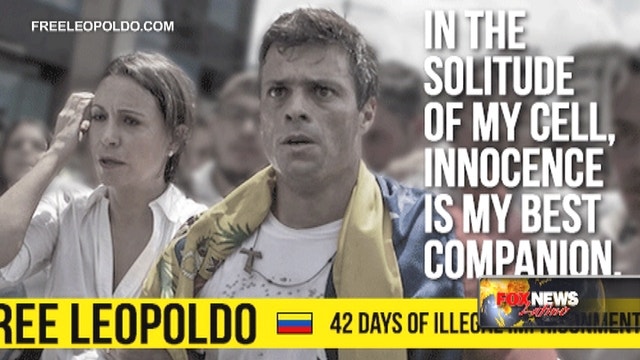

Now, Lopez sits in jail, along with many others who participated in the protests, which resulted in violent clashes with government security forces and Maduro supporters.

The Kenyon classmates whom Lopez rallied are now rallying around him, determined to raise awareness in the United States and Latin America about what they say is the grave injustice of their former fellow student’s imprisonment.

More than 30 protesters have died the past two months in skirmishes with police. The Maduro government says Lopez, who is being held without bail on charges of inciting violence and the destruction of property, caused the deaths by inciting the demonstrators, and that he is trying to overthrow the president.

His classmates launched a social media campaign shortly after his arrest in mid-February, setting up a “Free Leopoldo” Facebook page, website and Twitter account that have drawn thousands of followers. They want to pressure the Maduro government to release Lopez, and beyond that, push Latin American countries to speak up and take action against the Venezuelan government's brutal tactics in dealing with those who criticize it.

“Twenty years later, we see Leo’s leadership qualities that we saw at Kenyon exemplifying themselves at the highest level,” said another classmate, Leonardo Alcivar, one of the few other Latinos on the Midwestern campus at the time.

“To see this unjust illegal imprisonment at the hands of the Maduro government, it just moved all of us to act,” Alcivar said. “It just started with a few of us coming together via email, sharing the latest news about Leo, then we reached out to other schools with which he’s affiliated, and then we reached a broader universe.”

His classmates do not want what is happening to Lopez, and to others demonstrating against the more-than-50-percent inflation rate in Venezuela and oppressive tactics by Maduro officials, to get lost amid the global attention on Russia, Ukraine, and the missing Malaysian airliner.

It is, they say, the least they feel they can do for a friend who was always selfless, who was driven by a mission to improve conditions for others.

For Alcivar, who pursued a career in politics, working on campaigns of GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney and U.S. Senate contender Gabriel Gomez of Massachusetts, Lopez was a role model and mentor.

“Leo was a transformative figure in my life,” Alcivar said. “He came from a wealthy family, I was from Washington Heights in New York, and I was at Kenyon on a scholarship, otherwise I could not have been there.”

During one conversation at Kenyon, when Lopez sensed that Alcivar was feeling insecure, the Venezuelan gave his classmate a talk about self-pride.

“He said ‘My friend, nobody is better than you. Don’t you ever, ever forget that.’”

“That gave me confidence that I didn’t have in my personal life, and in my professional life,” he said.

Even in his mid-teens, Lopez managed to emerge as a leader.

At the Hun School, the Princeton, N.J. boarding school that Lopez attended in the 1980s, the Venezuelan was elected vice president of the student council, and chosen to be captain of both the crew and swimming teams.

His former classmates and teachers from Hun also are monitoring developments in the Venezuelan government's charges against Lopez, and expressing their support for him.

In a profile about Lopez that appeared this year in the Hun school newspaper, the writer noted: “Faculty and alumni recall a young man who, even then, was concerned for the people of Venezuela and had a plan to improve life in his homeland.”

Both Gluck and Alcivar visited Lopez in Venezuela before his arrest.

Alcivar went to see him 2008, when Lopez was mayor of Chacao, a district in Caracas.

“He was already under massive persecution by the government of Hugo Chavez,” he recalled. “But he was committed to putting together a coalition of people to ensure peaceful demonstrations for social and economic reforms and against the brutal oppression.”

He went with Lopez to some of the poorest areas of Caracas, and saw how people received him as a kind of rock star.

“Even places that were heavily Chavista, the people there greeted him with great respect and deep affinity,” he said.

He noticed that Lopez’s car was riddled with bullets – vestiges of an apparent assassination attempt that killed the then-mayor’s bodyguard.

“He had been in the car when someone shot at it,” Alcivar said. “He told me about the bodyguard. He said ‘Leonardo, he died in my arms.’”

But, Alcivar said, Lopez kept riding in that car.

“It was,” he said, “a sign of defiance.”