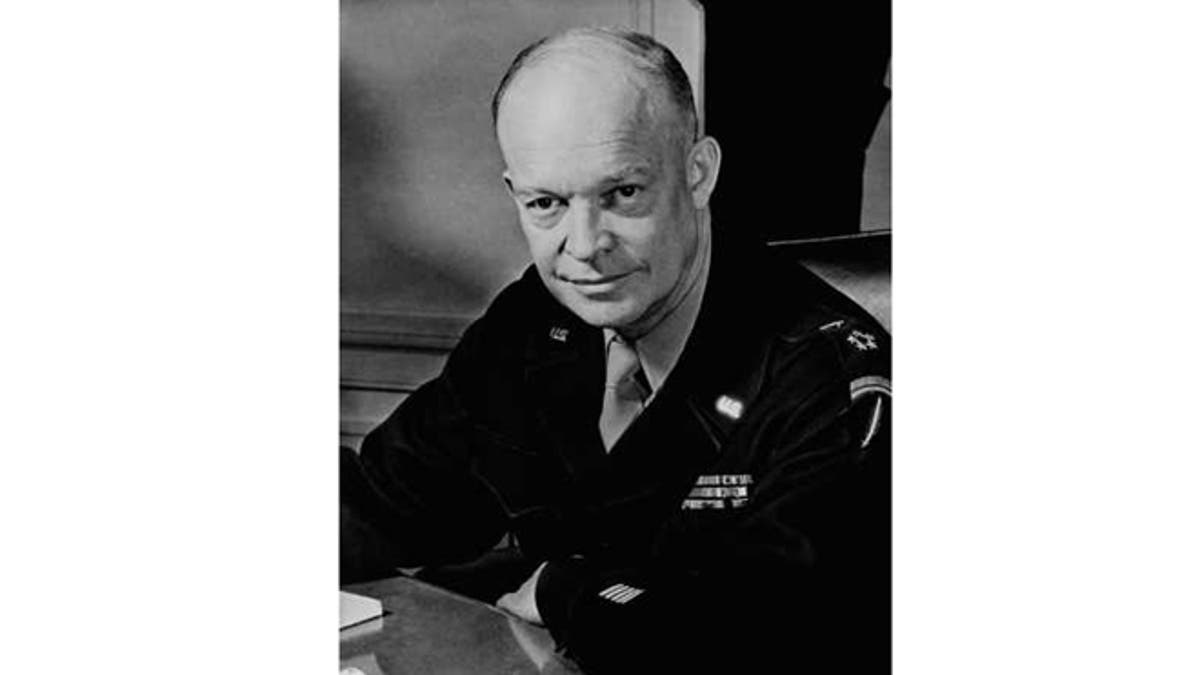

General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Supreme allied Commander, seated at his desk at his headquarters in the European Theater of Operations, February 1, 1945. He wears the Five-Star Cluster and Great Seal of the United States, insignia of the new rank of General of the Army. (AP)

American history is replete with tales of conflict between presidents and Congress, but rarely have both institutions been more in agreement than when they bestowed five-star ranks on eight admirals and generals near the end of World War II. The reason for such unanimity was unquestioned leadership by the recipients. Each of the men so honored with five stars had differing styles and personalities, but all had unshakeable reputations for making tough decisions and accepting responsibility for the results. All were unabashedly proud of the United States of America.

When these stars began to fall in December 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt was adamant that Admiral William D. Leahy receive the first five-star rank, making him a fleet admiral. Leahy was publicly unsung and little known, but as Roosevelt’s unassuming White House chief of staff, as well as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Leahy had been one of Roosevelt’s closest advisors since Leahy became Chief of Naval Operations in 1937. Leahy’s five-star promotion was dated December 15, 1944, and the other recipients followed one day after another, alternating between fleet admirals and generals of the army.

The army’s first general of the army appointment went to Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. Almost unflappable, genteel in his manner, Marshall was the ultimate team player and team builder. Whatever glories others found on far-flung battlefields or nurtured in the public’s perception of them, they all owed the organization and the resources that made their efforts possible to Marshall’s leadership.

Ernest J. King’s promotion to fleet admiral made him third on the five-star list. Gruff, demanding, and uncompromising, King was the overlooked global strategist of World War II planning councils. Grating though his personality was on superiors and subordinates alike, King, as Commander in Chief of the U.S. Fleet, ably managed a two-ocean war. While championing American commitments to the Pacific, he supported the flow of supplies to Russia, won the battle of the Atlantic against German U-boats, and made possible Allied amphibious landings from North Africa to Normandy.

The fourth five-star position belonged to the army. Although Dwight D. Eisenhower had skillfully held supreme allied commands across North Africa and Europe, politics and public image dictated that Douglas MacArthur receive five-star rank ahead of him. President Roosevelt recognized that in the minds of many Americans, MacArthur had come to personify the Pacific war effort.

The fifth set of five stars went to Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, known familiarly as CINCPAC. Nimitz, too, was a team builder who led by example at every level. He wasn’t given to tantrums as was King, but instead simply focused steely blue eyes on a subordinate and decreed, “Let’s get this done.”

Eisenhower got his five stars the next day. As a newly minted brigadier general at the war’s outset, Ike had pointedly expressed frustration over Admiral King’s demeanor. But after an encounter where Eisenhower stood his ground under King’s verbal barrage, he gained King’s respect and the two came to work well together despite their different styles.

President Roosevelt and Congress might have stopped with three fleet admirals and three generals of the army, but parity on the Joint Chiefs encouraged the appointment of Army Air Forces Chief of Staff Henry H. Arnold to five-star rank. Later, with a Department of the Air Force separate from the army, Arnold was honored as the only general of the air force and the only American to hold five-star rank in two military branches.

Who would be accorded the fourth set of five stars as a fleet admiral became a matter of some debate. The candidates were Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., and Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. Good friends though they were, they were polar opposites. Much like MacArthur, Halsey had come to personify the American naval effort in the Pacific with his gritty campaigns around Guadalcanal and a rough-and-tumble leadership style. Conversely, Raymond Spruance was a master of detail and a cerebral strategist who had a plan for every contingency. Unlike Halsey, Spruance eschewed publicity even as he led Nimitz’s drive through the central Pacific.

In the end, Halsey’s popular appeal brought him the eighth set of five stars in December 1945. A few years later, Congress authorized a fifth general of the army rank and awarded those stars to Omar N. Bradley, America’s celebrated field commander known as “the GI’s general.”

Congress might have done the same on the navy side by bestowing a fifth set of fleet admiral stars on Raymond Spruance. Nimitz argued strenuously in Spruance’s behalf but to no avail, and the ever-gracious Spruance simply said, “The fourth five-star promotion went where it belonged when Bill Halsey got it.”

The five-star admirals and generals were all different in style and personality, but the unquestioned leadership that each exhibited inspired the greatest generation of American fighting men and women and led them to victory in World War II. Despite bringing different talents and viewpoints to the table, they nonetheless worked together for a common purpose. They made the tough decisions and took responsibility for the results. We need more leaders willing to do the same today.