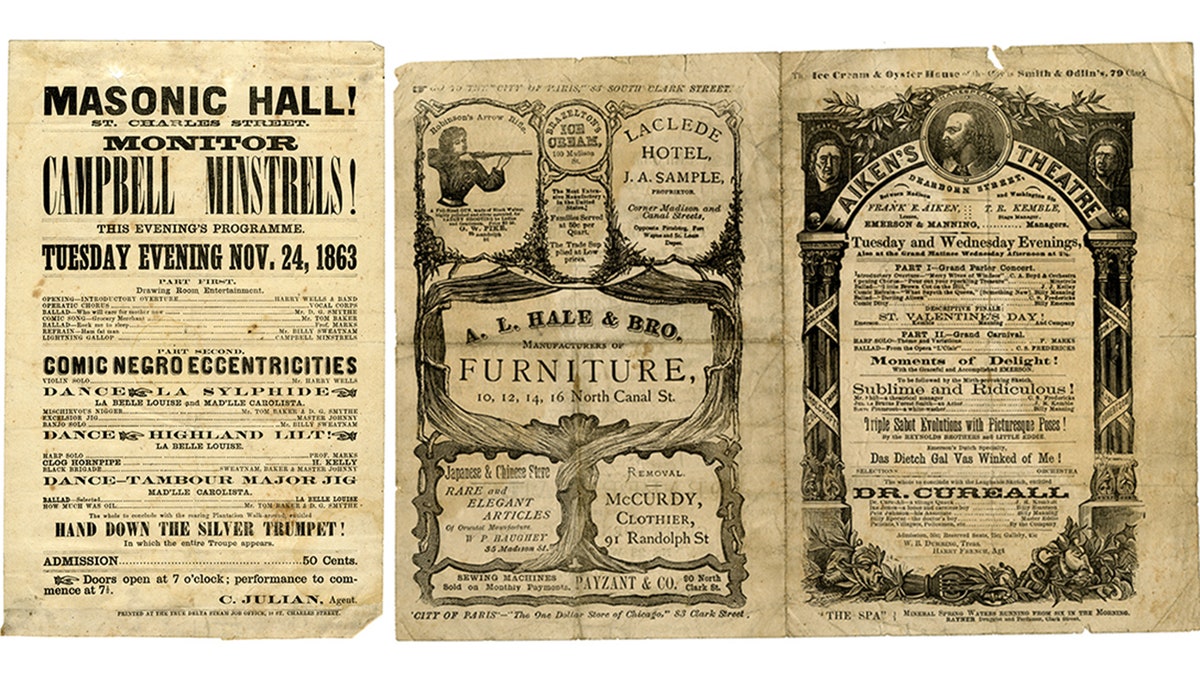

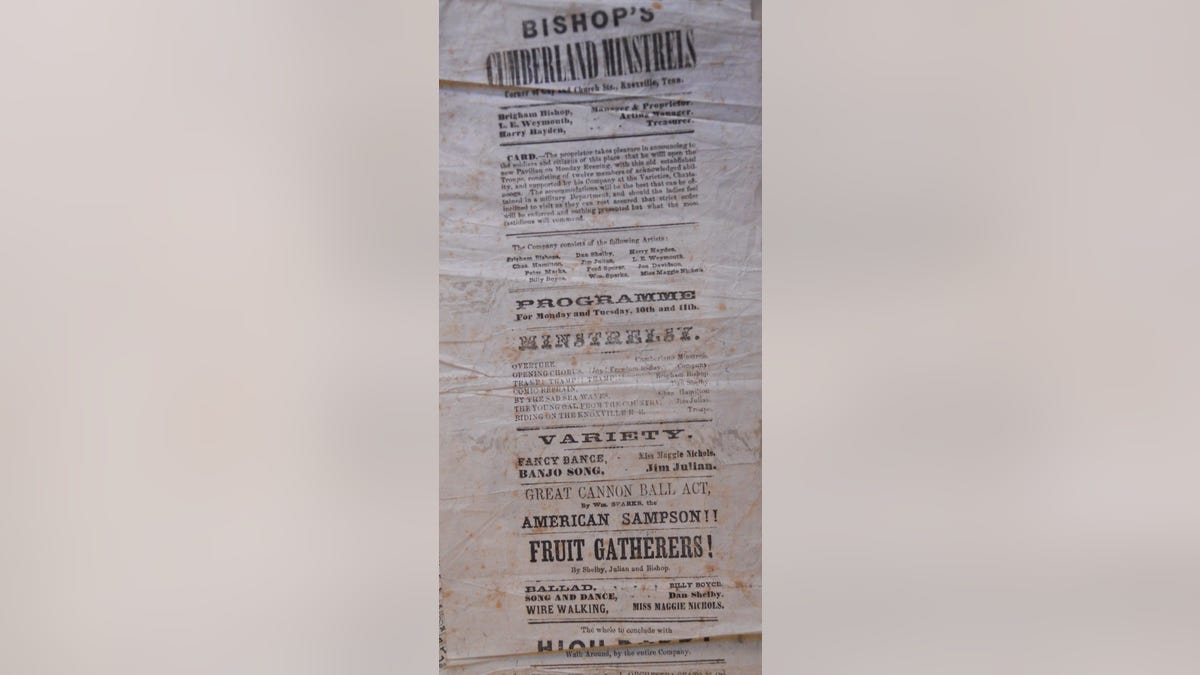

These handbills are from minstrel shows from the 1800s that were once owned by Peter Marks, a harpist who performed with the travelling troupe. (Peter Marks Minstrelsy Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Minstrel shows popular at the outbreak of the Civil War are often remembered for their role in perpetrating stereotypes about African Americans through blackface -- but for Mark Jessee, minstrel shows are an important part of his family’s history.

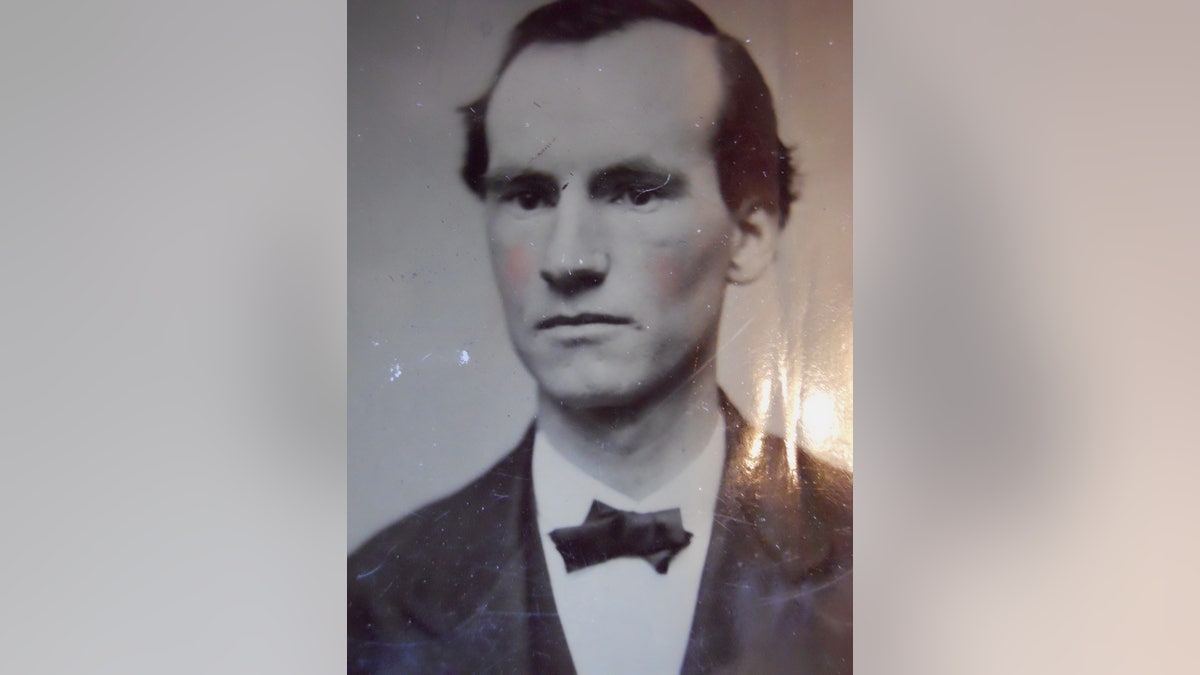

Jessee’s great-grandfather Peter Marks was said to be one of the premier traveling minstrel musicians in the United States during the Civil War. He was known for his harp solos.

Marks, known by his stage name Professor Marks, traveled from city to city across the Midwest entertaining folks seeking to escape the troubles looming between the Union and the Confederacy.

Peter Parks, known as Professor Marks, traveled across the Midwest as a harpist in minstrel shows. (Courtesy of Mark Jessee)

“I remember my mother saying that Professor Marks met Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill,” he told Fox News recently. “[But] as a small child, I wasn’t really interested in it.”

When Jessee’s mother passed away several years ago, he started cleaning out her belongings and found a treasure trove.

In one box, he discovered dozens of posters, sheet music, theater programs, newspaper articles and advertisements that his great-grandfather had saved from his travels.

“I couldn’t believe what I had seen,” he said. “I discovered something not only precious for the family, but American history was uncovered.”

Minstrelsy, created in the early 1800s, was a comedic form of entertainment that used song, dance, skits and musical performances as part of the program. Many white performers, such as Professor Marks, performed with blackened faces and characterized blacks as lazy, ignorant, hypersexual and prone to thievery.

Jessee said he understands the troupes’ history with blackface and added that the “N” word is only on a handful of the posters at the Smithsonian. He said that not all performers were in black face and that he believes there may have been debate over slavery among the performers.

“My family was never raised to be racist,” he said in an email. “As a matter of fact, my mom worked for Cesar Chavez in the late 1960s and my brother marched in Washington for civil rights in the 60s.”

Craig Orr, an acquisitions archivist with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., described the troupes as being a primitive version of “Saturday Night Live.” He said the skits in blackface were only a small part of the shows.

Minstrelsy, created in the early 1800s, was a comedic form of entertainment that used song, dance, skits, and musical performances as part of the program. (Courtesy of Mark Jessee)

“This was a form of live theater. It was the popular entertainment,” he said. “It was sketch artists, talent musicians and comedians.”

After uncovering the collection, Jessee spent some time restoring it before he started shopping it around to museums across the country. He spent nearly three years trying to get someone interested, but mostly got lukewarm responses.

“I don’t think they knew what I had,” he said. “I thought this was something unique that I had.”

In April 2014, the Smithsonian Institution came knocking.

“He did a thorough job of restoring the collection,” Orr, who contacted Jessee about the collection, told Fox News recently. “What immediately struck us was that he had more than 200 posters – or handbills that were handed out and posted around town [before a troupe came in].”

Orr said handbills in such good conditions are usually hard to find because they were designed to stick to wherever they are posted and “get lost to history.”

“You don’t usually find these things,” he said. “This is a very unique collection.”

The archivist said what make Jessee’s collection even more rare is that it’s connected to a specific person instead of a wide-range compilation of materials. Additionally, the documents are mostly from the Midwestern minstrel troupe circuit.

“Most of the handbills that survived are from the Northeast and New York circuits,” Orr said.

Minstrels became less popular after the Civil War and eventually transformed into burlesque shows before they stopped all-together.

The personal documents in the collection show that Marks was born in Ireland in 1843 and grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. By the time he was in his early twenties, he was a skilled musician who played piano, harp and guitar.

Before the Civil War, he performed with local troupes but enlisted in the Army. He served as a member of the Ohio militia for a month before leaving to continue his musical career.

He married Emma “Mary” McKitrick and together they had two sons, Eugene and Ralph. He ultimately left the minstrel circuit and went on to become a professor of music at the Cincinnati College of Music. He died in 1883.

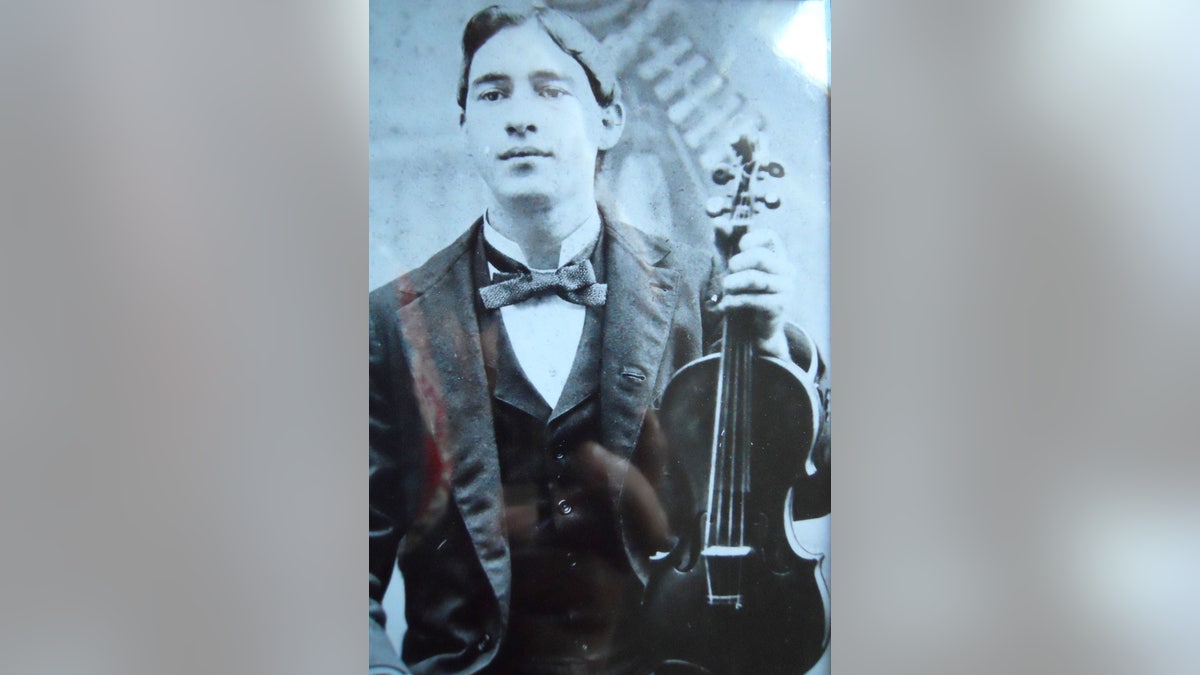

Mark Jessee is the grandson of Eugene Marks (pictured here), who is the son of Peter Marks. (Courtesy of Mark Jessee)

Jessee, 59, is the grandson of Eugene Marks, who played the violin. He said it’s an “honor” that his family’s history is part of the largest archive and collection in the world.

“I'm glad I was able to get this done [for my mother],” he said.

The collection is not currently on display at any of the Smithsonian museums, but can be sought for research.