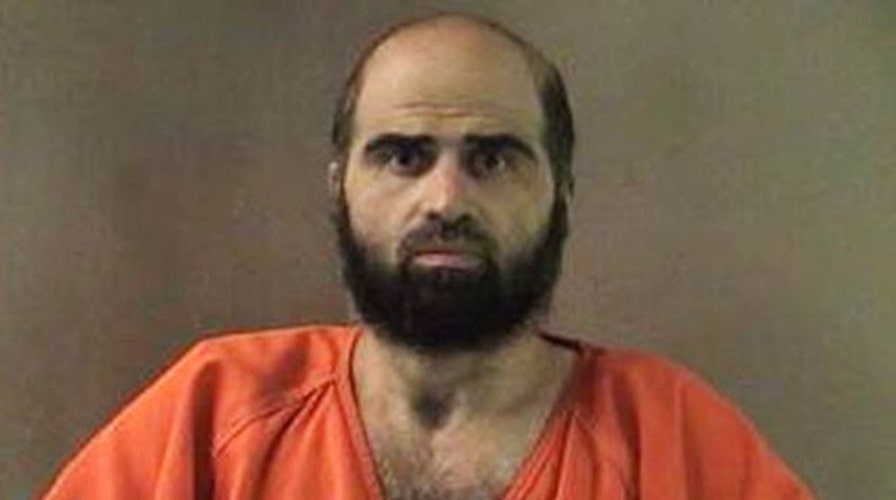

Nidal Hasan faces death penalty

Former Marine Corps JAG Christian Nagel on what we expect in court

FORT HOOD, Texas – Witness after witness testified to the heartbreak unleashed by Maj. Nidal Hasan in the 2009 Fort Hood shooting rampage, but the former Army psychiatrist and self-professed "soldier of Allah" sat mute in court, asking no questions as a military jury pondered his fate.

Hasan, an Army psychiatrist convicted of killing 13 people in the November 2009 attack, faces the death penalty as the sentencing phase of his trial begins Monday. But after admitting in opening arguments he was the killer, then barely bothering to question witnesses during the trial, it has become apparent that the Virginia-born Hasan could be seeking martyrdom.

As many as seven more people will get their chance Tuesday to tell jurors how Hasan changed their lives forever. If the jury was moved by the despair of several government witnesses who testified to the pain Hasan caused, he may get that wish.

Speaking through an interpreter, Juan Velez, the father of pregnant soldier Francheska Velez said Hasan's rampage took a bigger toll than most people know.

“That man did not just kill 13 that day, he killed 15," he said. "He killed my grandson, and he killed me. Slowly.”

Shoua Her, widow of Pfc. Kham Xiong, gave emotional and heartbreaking testimony about her husband and the father of her three children who she fell in love with in the eighth grade. She said her dreams of travel and a better life died with her husband.

“Vacations are now just dreams that I once had," she said. "My kids will not know their father but through stories and others memories of him.

“I miss him a lot. I miss his soft gentle hands, how he held me, he made me feel safe and secure," she continued. "Now the other side of the bed’s empty and cold. I feel dead but yet alive. He was my other half. He was my best friend."

Mick Engnehl, who was shot twice in the attack and underwent open heart surgery and still has a paralyzed right arm, said he cannot play with his young son, is afraid of crowds and fears he may never again find work.

“No one’s going to hire a paralyzed mechanic,” he said.

And Gale Hunt, whose son, Army Spc. Jason Hunt was killed in the attack, said the loss of her son haunts her every day.

"I miss his voice, I miss his little half crooked smile because he’s too cool to smile all the way," she said, her eyes welling with tears.

Earlier, the military judge presiding over the court martial warned Hasan that his life hangs in the balance as his trial entered the sentencing phase, but the Hasan declined to let his court-appointed attorneys help him avoid a death sentence.

"You understand that you are staking your life on the decisions that you make," Col. Tara Osborn, the trial judge, told Hasan on Friday following his conviction. "Still wish to proceed pro se?"

"I do," replied Hasan, who sat emotionless through the dramatic testimony.

Hasan showed no reaction after being found guilty last week by a military jury of opening fire on unarmed soldiers at the Texas Army post to protect insurgents abroad should be executed. Twelve of the dead were soldiers, including a pregnant private who pleaded for the unborn child's life. More than 30 others were wounded. Investigators collected more than 200 bullet casings at the site of the attack.

At the minimum, the 42-year-old Hasan, who was left paralyzed after being shot during his rampage, will spend the rest of his life in prison.

Osborn implored Hasan, who represented himself during the 14-day trial, to consider letting his standby attorneys take over for the sentencing phase. He declined.

Jurors deliberated for about seven hours before finding Hasan guilty on all counts. He gave them virtually no alternative, as he didn't present a defense or make a closing argument, and he only questioned three of the nearly 90 witnesses called by prosecutors.

His silence convinced his court-ordered standby attorneys that Hasan wants jurors to sentence him to death. Hasan told military mental health officials in 2010 that he could "still be a martyr" if he is executed.

The sentencing phase will be Hasan's last chance to say in court what he's spent the last four years telling the military, judges and journalists: that the killing of American soldiers preparing to deploy to Iraq and Afghanistan was necessary to protect Muslim insurgents.

Hasan was prohibited from making a "defense of others" strategy during the guilt or innocence phase of his trial, but he will have more latitude during the sentencing portion. This has led legal experts and his civilian lawyer, John Galligan, to believe that Hasan could put himself on the witness stand this week.

Osborn didn't ask Hasan whether he might testify following his conviction. But she did ask whether Hasan felt he had been subject to "illegal punishment" or been unfairly restricted since being put in custody after the shooting.

He told Osborn he wasn't ready to answer.

"I'm still working on that," Hasan said.

Prosecutors want Hasan to join just five other U.S. service members currently on military death row, and are planning to put more than a dozen grieving relatives on the witness stand. Three soldiers who survived being shot by Hasan but were left debilitated or unfit for service are also expected to testify.

But most will be widows, mothers, children and siblings of the slain, who are expected to tell a jury of 13 high-ranking military officers about their loves ones and describe the pain of living the last four years without them.

What they won't be allowed to talk about are their feelings toward Hasan or what punishment they think he deserves.

Osborn told military prosecutors Friday to make sure their witnesses understood what topics were out of bounds. She was also considering excluding some family photos that could be considered duplicative, such as two different pictures of a victim in uniform.

"I understand the family members have memories of their loved ones," Osborn said. "But that's not part of the ruling I must make in a court of law."

Jurors must be unanimous to sentence him to death.

No American soldier has been executed since 1961. Many military death row inmates have had their sentences overturned on appeal, which are automatic when jurors vote for the death penalty. The U.S. president must eventually approve a military death sentence.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.