(WMG/University of Warwick)

Researchers in the U.K. are using an assortment of high-tech methods – neutron imaging, XRF analysis, 360-degree laser scanning, 3D printing, and real-time X-ray videography – to get a clearer understanding of two Renaissance-era bronze statues believed to be made by Michelangelo.

University of Cambridge historians have teamed up with anatomists from the University of Warwick’s Warwick Medical School and engineers and imagers from the Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) on the project. The research team has set out to make accurate replicas of the original figures, according to a University of Warwick press release.

Back in February, Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum announced that two three feet-high bronze male nude figures could be linked to a drawing by a Michelangelo apprentice. The statues were originally credited to Michelangelo when part of Adolphe de Rothschild’s 19th century collection.

The Warwick and Cambridge team is trying to figure out why thick-walled casts of the original sculptures are less detailed by creating smaller replicas by sculptor Andrew Lacey, who is an expert in archaeo-metallurgy. Lacey will cast two smaller-scale replicas of the statues in addition to a full-size version. The replicas will be made from high-res scans of the original versions, according to the release.

This research team incorporated expertise from a wide range of disciplines – from medicine to technology.

(WMG/University of Warwick)

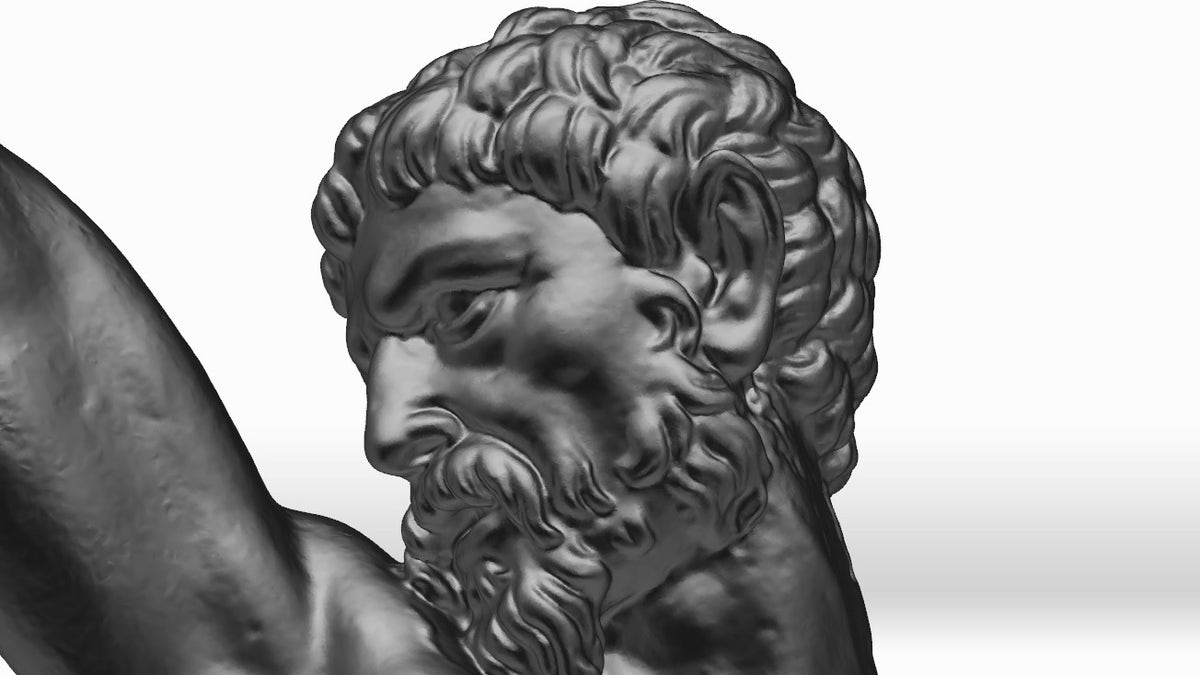

WMG’s Mark Williams led the team that scanned and created a 3D digital model of one of the original sculptures. The scanner is designed to capture the minutest details -- it can resolve features to below 100 microns. This is the same kind of technology used for crime scene investigation anatomical scans.

“It was fantastic to apply our technology to such an exciting project and help shed light on the origin of such beautiful statues,” Williams said. “Usually we are working on something engineering-related, so to be able to take our expertise and transfer that to something totally different and so historically significant was a really interesting opportunity.”

Propshop, based out of the iconic Pinewood film studios in London , used the scan to create 3D, full-scale and reduced-scale prints. Lacey took molds from these 3D printouts, utilizing alloys that are as close as possible to those used to forge the original sculptures. He then employed a furnace similar to that used during Michelangelo’s era.

In order to get a firmer grasp on this complex, classical casting process, William Griffiths, who is part of the Metallurgy and Materials Department at Birmingham University, shot real-time X-ray videos as the molten bronze was poured into the molds.

Peter Abrahams, a clinical anatomist from Warwick Medical School, examined the anatomy of the sculptures. He concluded that the sculptor must have performed human dissections, which were rare before 1543. Abrahams asserted that, in the Renaissance art world, only Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo had the correct “anatomical knowledge, grained through the regular dissection of corpses.”

“Some features of the anatomy on the two figures are not visible on observation alone and could only have been known through the practice of cutting open cadavers,” he added.

(WMG/University of Warwick)

So, what is the point of this multi-pronged, complicated replication process? It is all to help bring to life the artistry of the past and hopefully shed more light onto the origins of the sculptures.

“Thanks to this novel collaboration between art historians, conservation scientists, anatomists, engineers, prop-makers and artists, and through harnessing state-of-the-art equipment and imaging technologies, we can now reveal that these enigmatic bronzes were manufactured using some rather idiosyncratic working practices, which lends further weight to the early date already suggested by visual and preliminary technical analysis,” said Victoria Avery, keeper of applied arts at the Fitzwilliam Museum.