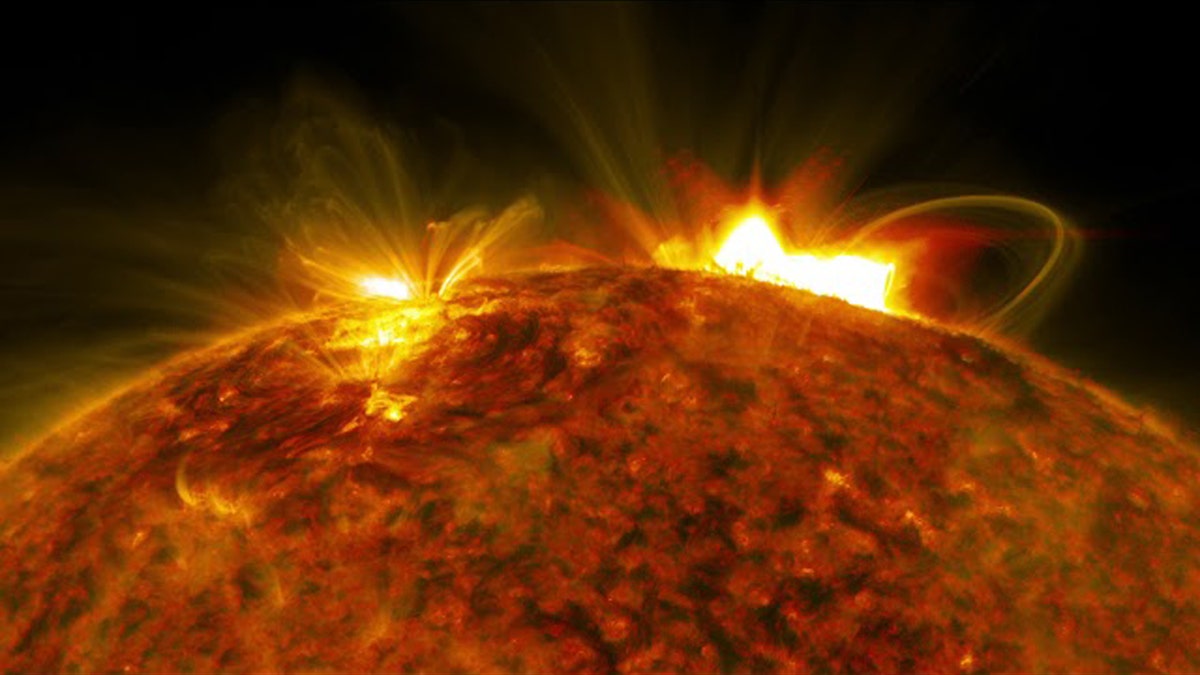

NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory captured an image of the massive flare that burst off the sun on Sept. 10, 2017. (Credit: NASA/Goddard/SDO)

Studies of a solar flare revealed something unexpected about the sun: its magnetic field is even stronger than scientists predicted.

Measuring that magnetic field within loops of material bursting out of the sun has been a tricky feat because of the interference of Earth's atmosphere. But a team led by David Kuridze, a solar physicist at Aberystwyth University in the United Kingdom, got lucky when they caught sight of a super-strong flare that the sun belched on Sept. 10, 2017.

The researchers spotted the flare using the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope at Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma in the Canary Islands. The solar telescope is a particularly powerful solar telescope, but its aperture (viewing area) allows researchers to examine only 1 percent of the sun at a time. Fortunately, the team was looking at exactly the right spot when a solar flare erupted.

Related: Huge New Solar Telescope Shares Science Excitement with Neighboring Schools

This good luck allowed them to measure the flare's magnetic field strength high in the sun's corona, or atmosphere.

The sun is well-known for its magnetic activity, including periodic flares that rise from the surface when magnetic lines twist and "snap." Flares are associated with coronal mass ejections, which send streams of charged particles into space. If these particles are aimed toward Earth, they can disrupt satellites or cause colorful auroral displays.

The new finding could help scientists better understand what is happening in the corona, the superheated part of the sun's upper atmosphere that is visible to humans only during a total solar eclipse. The corona is being studied by a NASA spacecraft called the Parker Solar Probe, which is zooming closer to the sun than any other spacecraft before it.

"Everything that happens in the sun's outer atmosphere is dominated by the magnetic field, but we have very few measurements of its strength and spatial characteristics," Kuridze said in a statement. "These are critical parameters, the most important for the physics of the solar corona. It is a little like trying to understand the Earth's climate without being able to measure its temperature at various geographical locations."

The research is described in a paper that has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal and that was posted to the preprint server arXiv.org in February.

- Stunning Photos of Solar Flares & Sun Storms

- Stunning Animation of a Solar Flare Captures Its Life from Birth to Death

- NASA's Parker Solar Probe Mission to the Sun in Pictures

Original article on Space.com.