Stalin’s effort to hide Hitler’s death

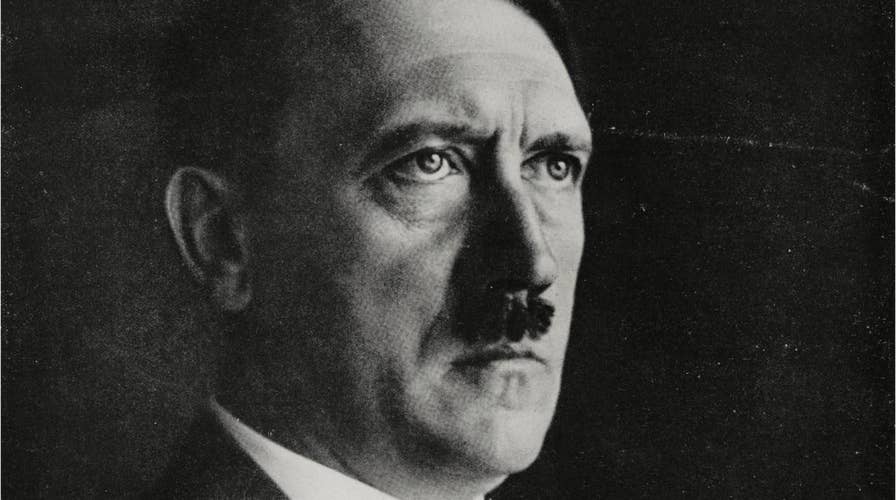

Käthe Heusermann was in solitary confinement for six years and then sentenced to ten years of hard labor in a Gulag by Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union. Her crime was knowing the truth about Adolf Hitler’s death.

Berlin’s ruins still smoldered as three Soviet military intelligence officers questioned a tall, lithe blonde in 1945. A Red Army lieutenant, the group’s translator, opened the burgundy satin cover of a cheap jewelry box and showed her its contents.

Nestled inside were charred human teeth, gold dental crowns and a complete lower jaw.

“I took the dental bridge in my hand,” Käthe Heusermann wrote decades later. “I looked for an unmistakable sign. I found it immediately, took a deep breath and blurted out, ‘These are the teeth of Adolf Hitler.’ I was showered with expressions of gratitude.”

Within weeks, Heusermann was in solitary confinement in a notorious Moscow prison — her reward for telling Josef Stalin an irksome truth.

When Berlin fell on May 2, 1945, front-line Allied troops were desperate to find Hitler. Years of fighting Nazis convinced them that nothing less than Hitler’s death would vanquish the Third Reich.

The Führer had spent the war’s final weeks in a fortified bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery building. Interpreter Elena Rzhevskaya, then 25, helped comb through the warren of underground rooms, interrogating survivors and seeking clues to his fate.

Rzhevskaya’s “Memoirs of a Wartime Interpreter” (Greenhill Books), out now for the first time in English, tells their detective story.

Medical examiners suspected that a burned corpse found in the chancellery’s enclosed courtyard — so damaged that it could not be positively identified — was Hitler’s. They wrenched the teeth and their extensive bridgework from the mouth, placed them in the secondhand jewelry box and entrusted the macabre package to Rzhevskaya.

“It burdened and oppressed me,” she wrote. “Now the crucial task was, at all costs, to find Hitler’s dentist.”

Dr. Hugo Blaschke had tended the Führer’s notoriously bad teeth since 1932. An informant told the Soviets that Blaschke had fled to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s Alpine stronghold, weeks before.

The Russians tracked down a man who knew Blaschke’s assistant like a daughter. “You mean Käthchen,” said Dr. Theodor Bruck. “She is at home in her apartment right on our doorstep.”

Käthe Heusermann trained under Bruck in the early 1930s, but the Jewish dentist had gone underground to evade the regime’s persecution, and she went on to work for Blaschke. The woman who gave Hitler the rinse-and-spit routine secretly supported Bruck for years with special rations and extra food vouchers she received as a member of the Führer’s extended staff. The discovery of their relationship could have been fatal.

Heusermann told the Russians that Blaschke kept a special office within the Reich Chancellery’s bunker. She led them to the dentistry room, still stocked with its tools, reclining chair — and Hitler’s dental X-rays, “irrefutable evidence that Hitler was dead,” Rzhevskaya wrote.

The facts were reported directly to Soviet dictator Stalin. Yet he refused to let his government dispel the wild rumors — that Hitler had sailed to Argentina or was hiding in fascist Spain — that had already started to circulate.

“We shall not make this public,” he told his closest deputies. “The capitalist encirclement continues.”

The tyrannical Stalin had no need to explain his decision to underlings, so historians have had to guess at his purpose. Holding this critical fact back from his supposed allies may have been the first paranoid power play of the nascent Cold War, some experts say.

In late May 1945, two weeks after receiving the irrefutable evidence of Hitler’s demise, Stalin was personally spinning crazy conspiracy theories about the despot’s submarine escape to Japan during delicate negotiations with US envoy Harry Hopkins.

“He loathed the idea of détente,” Rzhevskaya believed. “If Hitler was alive, Nazism was not yet vanquished and the world was still in danger … Stalin sat on the truth.”

That meant hushing up all those who could prove Hitler was dead. Heusermann was arrested, secretly sent to Moscow and held in solitary confinement for six years without a trial.

“In August 1951, I was finally charged,” she wrote. “By my voluntary participation in Hitler’s dental treatment, [they said] I had helped the bourgeois German state to prolong the war.”

Sentenced to 10 years in the gulag, she was loaded into a cattle truck for the 2,800-mile trip to a labor camp in central Siberia. Years in solitary made her too weak to meet her work quota. She barely survived.

By 1955, Stalin had died and West Germany negotiated the return of German prisoners. Heusermann went home to Berlin. Her soldier fiancé had married in her absence. She went back into dentistry and died in 1993.

Rzhevskaya published several books about her wartime experiences. But it took her 50 years of research in the USSR’s secret archives to uncover the monstrous truth of what her nation had done to her star witness — and to reveal that Stalin had deliberately hidden the proof of Hitler’s death.

“If we had not found Käthe … Hitler, as Stalin wanted, would have remained a myth and a mystery,” she wrote. “But what suffering we had unwittingly doomed Käthe Heusermann to endure.”

This story originally appeared in the New York Post.