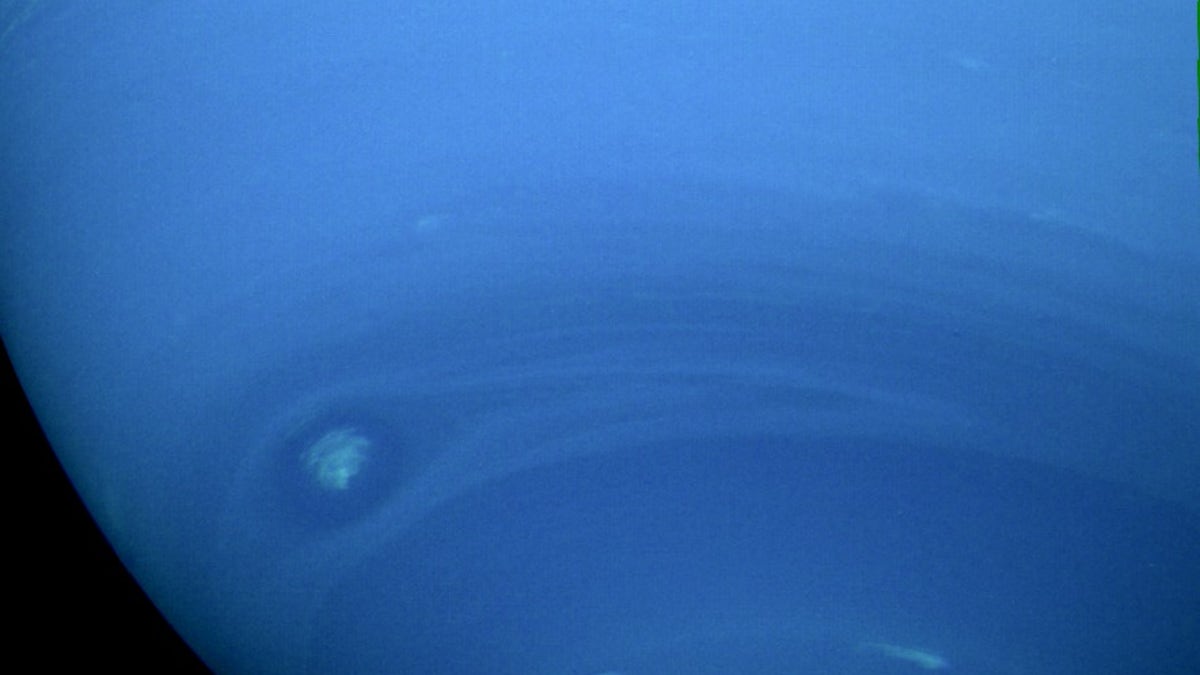

The giant, dark storms on Neptune are impermanent features on the distant planet. (NASA/JPL)

A dark storm on Neptune, once big enough to reach from Boston to Portugal, is dwindling to nothing as the Hubble Space Telescope keeps watch.

When NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by Neptune in 1989, it observed large, dark storms inhabiting the distant planet's atmosphere. Since then, scientists have monitored Neptune using the Hubble Space Telescope and seen new storms develop.

But unlike Jupiter's Great Red Spot, a storm which has been roiling for at least two centuries, the storms brewing on the windy planet Neptune come and go in just a few years — and now, for the first time, researchers have seen one begin to disappear, NASA officials said in a statement. [The Amazing Blue Planet Neptune in Photos]

"It looks like we're capturing the demise of this dark vortex, and it's different from what well-known studies led us to expect," Michael Wong, a researcher at the University of California at Berkeley and lead author on the new work, said in the statement. Previous simulations suggested that the vortex would drift toward the planet's equator, and "once the vortex got too close to the equator, it would break up and perhaps create a spectacular outburst of cloud activity."

More From Space.com

But instead, it drifted toward the planet's south pole and is quietly fading away. The vortex was 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) across the long axis when Hubble spotted it in 2015, and now it's down to 2,300 miles (3,700 km) across.

The planet's anticyclones, like this dark storm, pull up dark material from deeper in Neptune's atmosphere as they spin, carried along by three wind jets circling the planet: one going west at the equator, and two going east near each of the poles. (Neptune's powerful winds are the fastest ever detected in the solar system and can reach supersonic speeds.) Careful tracking by Hubble can help reveal how common the storms are, as well as what's going on further down.

"No facilities other than Hubble and Voyager have observed these vortices," Wong said. "For now, only Hubble can provide the data we need to understand how common or rare these fascinating Neptunian weather systems may be."

The new work was detailed Feb. 15 in the Astronomical Journal.