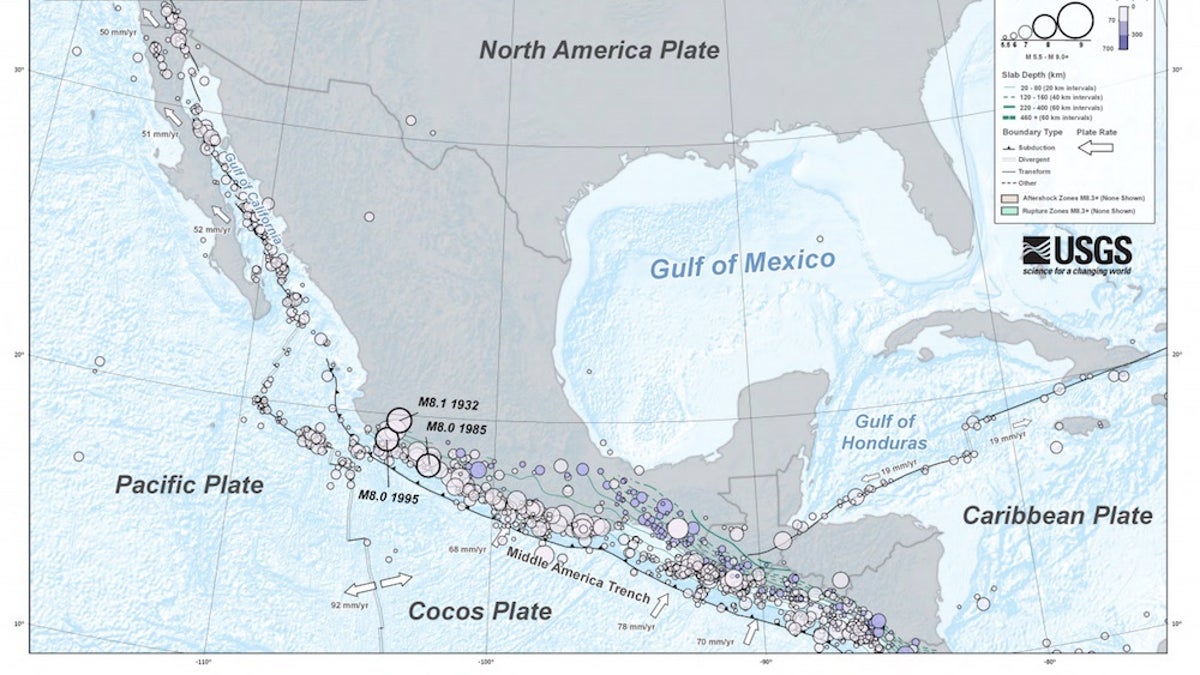

In the 20th century, Mexico was hit by hundreds of earthquakes, including about 20 magnitude-6.5 or higher quakes that struck around Mexico City. (USGS)

Over the past two weeks, Mexico has experienced a lot of shaking.

On Sept. 8, a magnitude-8.1 earthquake struck 54 miles (87 kilometers) southwest of Pijijiapan, which sits just above the Mexico-Guatemala border. Eleven days later, a magnitude-7.1 quake struck 3 miles (5 km) east of Raboso, near Mexico City. And today (Sept. 21), another quake — a magnitude 4.8 — hit just outside Pijijiapan.

While Mexico's position along major tectonic fault lines makes it a hotbed of seismic activity, the frequency of these powerful earthquakes begs the question: Are these quakes happening more often? [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

Not likely, said Gavin Hayes, a research geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey's National Earthquake Information Center.

"Mexico is very prone to earthquakes," he said, "so earthquakes of this size in Mexico are not unusual. Getting two in a row of this size so close together is unusual but not unexpected."

In the grand, slow-moving world of tectonic plates, Mexico is situated at an unfortunate location: It rests at the southern edge of the North American Plate, putting it right at the point where it meets the Pacific Plate, the Cocos Plate and the Caribbean Plate.

The quakes occur because all of these plates are moving in different directions, and as they collide or rub against each other, this movement can unleash destructive forces. While these tectonic events usually occur along coastlines, like near Pijijiapan, the Cocos Plate has a unique conformation that explains why so many earthquakes are hitting Mexico City, which lies farther inland, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

While the North American landmass is slowly moving west, the Cocos Plate is traveling northeast. As they push against each other, the Cocos Plate, which carries the seafloor and is denser than plates carrying land, is forced underneath, into the Earth's mantle, according to the USGS.

But Hayes said that although most of these above-below collisions, called subduction zones, involve one point of descent, the Cocos Plate sinks a bit and then flattens out for a long expanse before it begins to sink again. Because the location at which it sinks is spread out, the resulting earthquakes often occur farther inland than they would at a typical subduction zone.

"I think this perhaps facilitated the shaking we saw two days ago," Hayes said.

Some large earthquakes can trigger large aftershocks, but that's almost certainly not what happened here, according to Hayes. For one, the two epicenters are too far away from each other to be causally related. Even though both earthquakes occurred on the same subduction slab that goes beneath Central America, they were caused by different fault lines, he said.

As such, it was more of a coincidence than anything else that both fault lines were "ready to go," Hayes said.

But because there are so many fault lines along the subduction zone that runs down the coast of Mexico, Hayes thinks it's reasonable to assume that there will be more large earthquakes in the region in the future, but not any more than one might normally expect.

"It's still a significant hazard," he said.

Original article on Live Science.