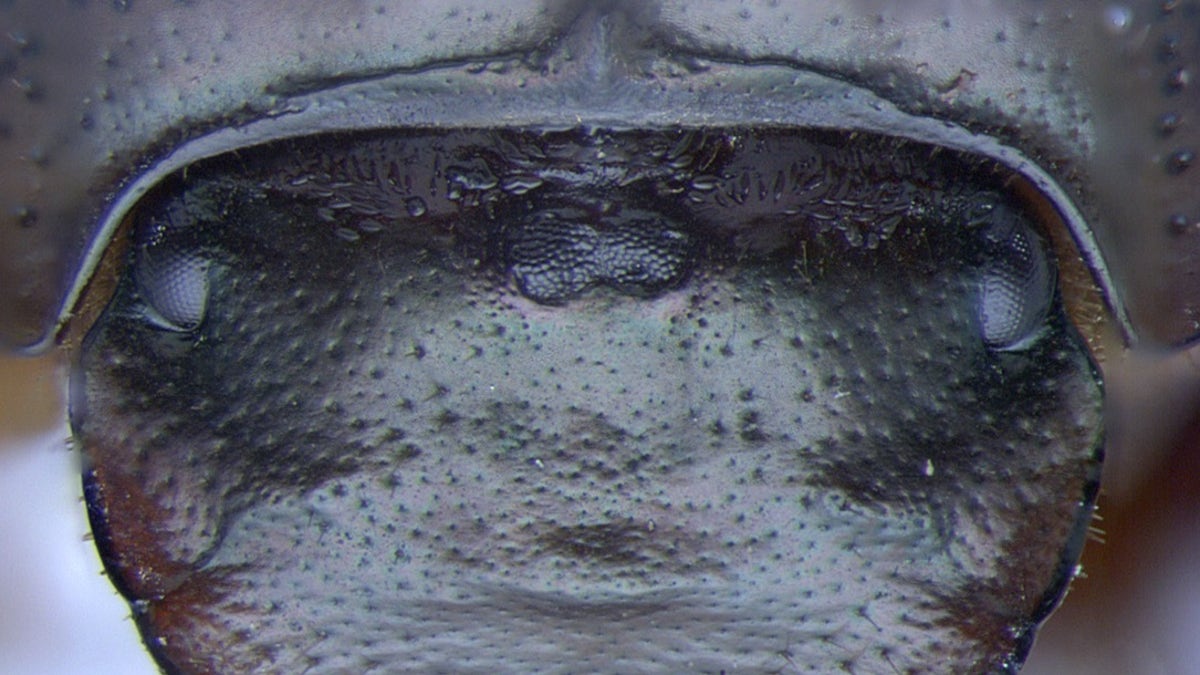

Without the orthodenticle gene, this dung beetle (<em>Onthophagus Sagittarius</em>) grows an extra compound eye at the top center of its head. (Indiana University)

Baby beetles with three compound eyes, one in the center of their heads, are teaching scientists something about how new facial traits evolve.

The researchers focused on a group of dung beetles with horns in the genus Onthophagus. They were surprised to find that when they inactivated a certain gene, the beetle larvae developed into adults with no head horns. Instead, another compound eye popped up in an odd place.

"We were amazed that shutting down a gene could not only turn off development of horns and major regions of the head, but also turn on the development of very complex structures such as compound eyes in a new location," study leader Eduardo Zattara, a postdoctoral researcher at Indiana University's Department of Biology, said in a statement. [See Images of Dung Beetles Dancing on Their Poop Balls]

Like other insects, beetles hatch as larvae that then grow and metamorphose into adults. Based on research in flour beetles in the Tribolium genus, Zattara and his colleagues knew that certain genes are key to making the heads of the beetle larvae. But whether these same genes played any role in shaping adult heads was a mystery.

Related:

To find out, they figured out which parts of the larval heads turned into different parts of the adult head and then turned off some of those genes. (That research was a separate study led by Indiana University's Hannah Busey.) They found the intriguing "extra eye" results when they knocked out the so-called orthodenticle gene. Without that gene, most animal embryos don't develop a head or brain, the researchers noted.

Though beetle embryos also need orthodenticle to develop heads, nobody knew how the gene functioned in beetle larvae or adults. Turns out, during metamorphosis, the gene reorganizes the head and integrates the beetles' horns.

Shutting off orthodenticle in flour beetles did not have the same effect — they didn't grow extra eyes or lose their horns — suggesting the gene acquired this new function only in the heads of horned beetles, the researchers noted.

"Here we have a situation where a gene is already in the right place — the head — just not at the right time — the embryo instead of the adult," study researcher Armin Moczek, a biology professor at Indiana University, said in the statement. "By allowing the gene's availability to linger into later stages of development, it becomes easier to envision how it could then be eventually captured by evolution and used for a new function, such as the positioning of horns."

The research, funded by the National Science Foundation, was published in July in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Original article on Live Science. Copyright 2016 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.