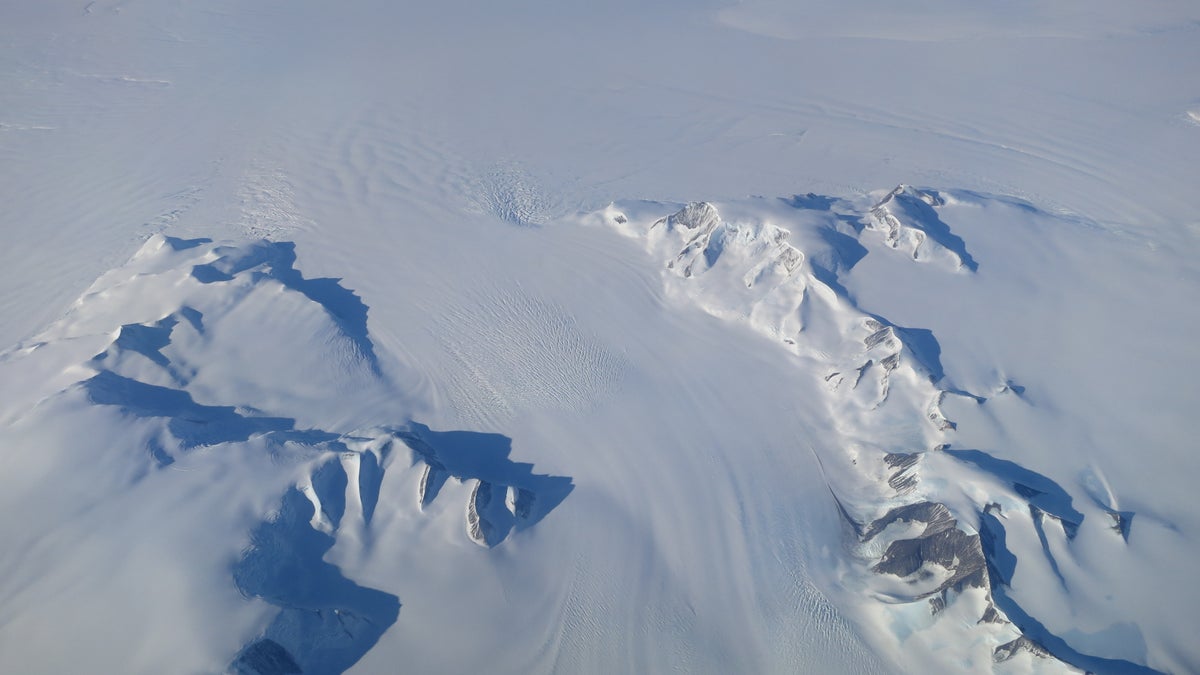

A new NASA study says that Antarctica is overall accumulating ice. Still, areas of the continent, like the Antarctic Peninsula photographed above, have increased their mass loss in the last decades. (NASA's Operation IceBridge)

Snow that began piling up 10,000 years ago in Antarctica is adding enough ice to offset the increased losses due to thinning glaciers, according to a NASA study.

The latest findings appear to challenge other studies including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2013 report, which found that Antarctica is overall losing land ice.

Related: On Antarctica, scientists find glaciers melting at an accelerating pace, threatening havoc

“We’re essentially in agreement with other studies that show an increase in ice discharge in the Antarctic Peninsula and the Thwaites and Pine Island region of West Antarctica,” Jay Zwally, a glaciologist with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and lead author of the study, which was published on Oct. 30 in the Journal of Glaciology, said in a statement.

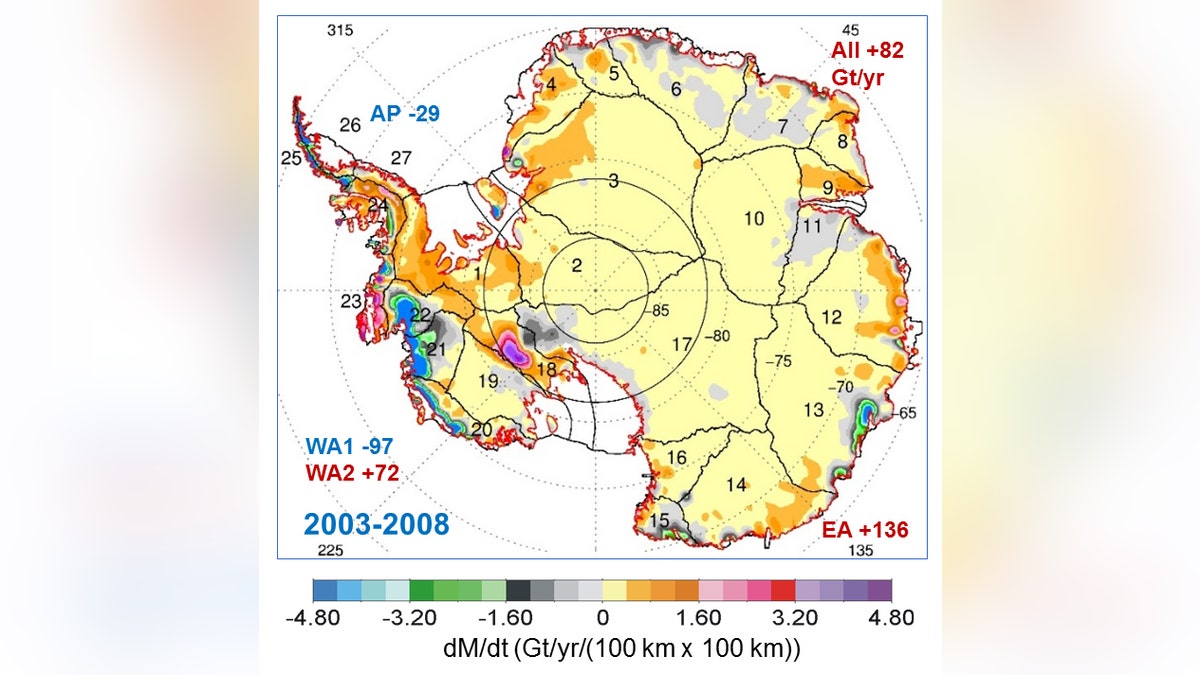

Map showing the rates of mass changes from ICESat 2003-2008 over Antarctica. Sums are for all of Antarctica: East Antarctica (EA, 2-17); interior West Antarctica (WA2, 1, 18, 19, and 23); coastal West Antarctica (WA1, 20-21); and the Antarctic Peninsula (24-27). A gigaton (Gt) corresponds to a billion metric tons, or 1.1 billion U.S. tons. (Jay Zwally/ Journal of Glaciology)

“Our main disagreement is for East Antarctica and the interior of West Antarctica – there, we see an ice gain that exceeds the losses in the other areas.” Zwally said, adding that his team “measured small height changes over large areas, as well as the large changes observed over smaller areas.”

Related: Robot gliders see how Antarctic ice melts from below

According to the new analysis of satellite data, the Antarctic ice sheet showed a net gain of 112 billion tons of ice a year from 1992 to 2001. That net gain slowed to 82 billion tons of ice per year between 2003 and 2008. The mass gain from the thickening of East Antarctica remained steady from 1992 to 2008 at 200 billion tons per year, while the ice losses from the coastal regions of West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula increased by 65 billion tons per year.

To quantify whether ice sheets are growing or shrinking, scientists measure changes in surface height with satellite altimeters. In locations where the amount of new snowfall accumulating on an ice sheet is not equal to the ice flow downward and outward to the ocean, the surface height changes and the ice-sheet mass grows or shrinks.

To assess the amount of snow accumulation, the researchers used meteorological data beginning in 1979 to show that the snowfall in East Antarctica actually decreased by 11 billion tons per year. They also used information on snow accumulation for tens of thousands of years, derived by other scientists from ice cores.

Related: Active volcano discovered under Antarctic ice sheet

“At the end of the last Ice Age, the air became warmer and carried more moisture across the continent, doubling the amount of snow dropped on the ice sheet,” Zwally said.

The extra snowfall that began 10,000 years ago has been slowly accumulating on the ice sheet and compacting into solid ice over millennia, thickening the ice in East Antarctica and the interior of West Antarctica by an average of 0.7 inches per year. This small thickening, sustained over thousands of years and spread over the vast expanse of these sectors of Antarctica, corresponds to a very large gain of ice – enough to outweigh the losses from fast-flowing glaciers in other parts of the continent and reduce global sea level rise.

“The good news is that Antarctica is not currently contributing to sea level rise, but is taking 0.23 millimeters per year away,” Zwally said. “But this is also bad news. If the 0.27 millimeters per year of sea level rise attributed to Antarctica in the IPCC report is not really coming from Antarctica, there must be some other contribution to sea level rise that is not accounted for.”

The study has caused quite a stir in the community of scientists who work in Antarctica, with some questioning the reliability of the satellite data and saying it does little to change the narrative that the continent is losing mass.

Others said it demonstrates the challenges of trying to assess the state of ice sheets on such a huge land mass, where time scales and environmental factors often differ marketedly.

A seperate study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters this week found snow accumulation has dramatically increased on West Antarctica’s coastal ice sheet in the 20th century. But one of the study's authors, Elizabeth Thomas, a paleoclimatologist with the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge, said many of the same factors leading to increased snowfall also have been found to be responsible for the thinning of the ice shelves.

"In fact, having more snowfall doesn't necessarily balance the thinning. They are both a symptom of the same thing," she told Fox News. "They are connected. Rather than me saying there has been an increase in snow fall and that is a good thing if you like, it's actually probably a symptom of the same thing. More snowfall probably means more thinning from the wind driven processes."

Earlier this year, a study in Nature Climate Change found that global sea levels were rising faster than previously thought. Researchers used satellite data combined with tidal gauge information and GPS measurements to overturn previous suggestions that rates had slowed in the past decade.

Another study by Harvard University's Carling Hay and his colleagues in Nature examined rates of sea level rise before 1990 and found they had been overestimated by about 30 percent. That means the acceleration in sea-level rise in the past two decades is greater than previously thought.

Most researchers blamed the rising seas on melting ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica and shrinking glaciers, triggered by the rise in heat-trapping, greenhouse gas emissions.

But even if Antarctica isn’t part of the mix now, that could change in the future.

“If the losses of the Antarctic Peninsula and parts of West Antarctica continue to increase at the same rate they’ve been increasing for the last two decades, the losses will catch up with the long-term gain in East Antarctica in 20 or 30 years - I don’t think there will be enough snowfall increase to offset these losses,” said Zwally.