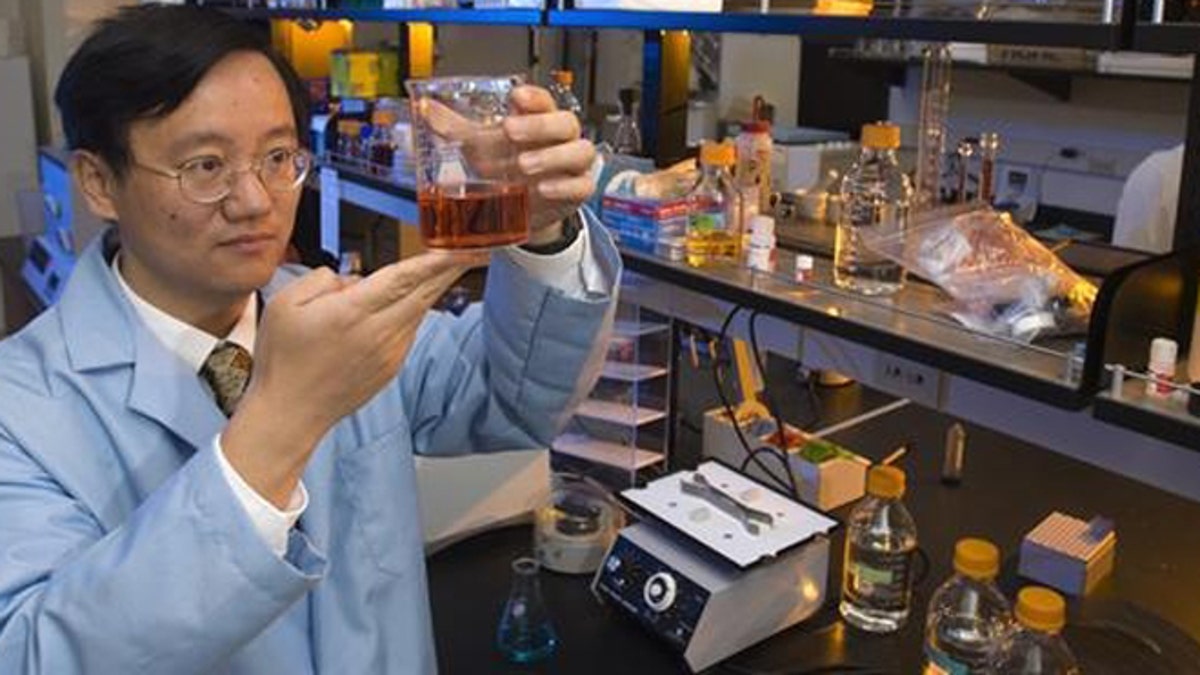

In the future, restaurants may serve woodchips the way they serve mashed potatoes and grits today. Thats what Virginia Tech professor Y.H. Percival Zhang is promising the world. (Virginia Tech)

Would you like wood chips with that?

Someday, restaurants will serve wood chips the same way they now serve mashed potatoes and grits. Also on the menu will be corn stems, husks and other unappetizing plant parts. And what’s more, diners will love the stuff.

That’s what Virginia Tech professor Y.H. Percival Zhang is promising the world.

Zhang, who studies biological systems engineering at the university’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, has developed a process that can transform wood chips, corn stems and other agricultural refuse into edible starches. And he hopes to do it someday in a facility that will look like a giant brewery.

Plants everywhere consist of cellulose—the substance that makes up plant cell walls and vegetable fibers like cotton. But in its raw form, cellulose is inedible. It’s too coarse, it’s not tasty, and humans can’t digest it properly. But cellulose and starch have the same chemical formula — they are polysaccharides, which means their molecules are chains of glucose units, or sugars. The only difference is in their chemical bonds.

- Nine unopened Dead Sea Scrolls found

- High-tech fixes for winter’s potholes

- SpaceX’s amazing ‘grasshopper’ rocket lands on legs

- Chimpanzees can play video games better than kindergartners

- T. rex had a small, cute cousin

- Why passenger cellphones can’t help locate missing Malaysian air jet

- Supergenius high school student wins Intel Science Talent Search

“Both of them are made by sugars, but they use different linkages between the glucose units,” Zhang said in an interview.

Edible starches such as tapioca and potato consist of glucose units joined by alpha-1,4-glycosidic bonds and alpha-1,6-glycosidic bonds, a type of link between sugar molecules. When we digest those starches, our bodies produce an enzyme, amylase, which breaks the bonds and turns the starches into sugar.

Inedible cellulose consists of glucose units joined by different links, named beta 1,4-glycosidic bonds. These bonds can be broken down by a different enzyme, cellulase, but our bodies don’t produce it. “That’s why humans can’t eat cellulose,” Zhang said.

But here’s good news, bark lovers: Zhang has found the answer.

If the beta bonds are converted into alpha bonds, the coarse cellulose turns into a soft, powdery substance like corn starch – and Zhang and his team have developed a process that restructures the bonds to do just that. “Our idea was to use enzymes, which can break down beta 1,4 bonds,” Zhang said, “then link them again and form new bonds as the alpha ones.”

Zhang’s process essentially creates a giant stomach. He takes corn stover -- a mix of corn stalks, leaves and even weeds and grasses -- and stirs different types of enzymes into it.

“It’s similar to the human body, which also uses various enzymes, one after another, to break down foods,” he said. The resulting amylose looks and tastes just like a regular starch. “It tastes a little sweet,” Zhang said, adding that unfortunately, “there’s no ready recipe for cooking amylose.”

Well . . . not yet. But there will be.

Zhang developed the process in his lab bioreactor, a container not much larger than a syringe. But the process is easy to scale. An industrial bioreactor would look like a typical brewery vat used for fermenting beer—only instead of grain, it would use corn stover, and instead of yeast, it would use enzymes.

“In our vision, we will produce this starch in a factory called a biorefinery,” Zhang said. He estimates production costs will be very low because enzymes are cheap and reusable, and agricultural refuse is aplenty. “Corn stover is the number one agricultural refuse in the U.S.,” Zhang said. “The ultimate cost may be nearly zero.”

In addition to amylose, the other product of the reaction is ethanol, which can be used as biofuel, thus helping solve the world’s fuel problem.

But Zhang’s method has the potential to solve an even more important global challenge—world hunger. Cellulose is the earth’s most abundant carbohydrate. It makes up the cellular structure of all plants — crops and weeds, including stalks, stems, branches, leaves, trunks and bark. Plants produce about 40 times more cellulose than edible starch, and a lot of it is wasted.

“Every ton of cereals harvested is usually accompanied by the production of two to three tons of cellulose-rich crop residues, most of which are burned or wasted rather than used for cellulosic biorefineries,” Zhang and his colleagues wrote in a recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

With Zhang’s method, any plant material from weed to wood can be turned into food. So far, the team hasn’t found an investor to build the first brewery-like biorefinery, but Zhang hopes countries with large populations like China and India may become interested.

Amylose is also healthier than the starches used in food production today because it breaks down slowly in the digestive tract. Foods with high amylose content, such as long-grain rice, don’t cause sugar spikes and are diabetic-friendly.

So if one day, your waiter asks “Would you like wood chips with that?” just say yes. You’ll be eating carbs so healthy you’ll be barking for more.