War Games: Eyes get bionic

Allison Barrie on the latest technologies being used to bring sight to the blind

The world’s only bionic eyes -- implants that can bring sight to the blind -- keep getting better.

Created by Second Sight Medical Products and recently approved by the FDA, the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System uses an implanted camera and computer to convert the world at large into electronic signals, enabling the brain to see.

It’s the first implanted device that can provide sight to people 25 and older who have lost their vision from degenerative eye diseases like macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa.

And results just published in the latest British Journal of Ophthalmology indicate they’re even better than previously thought: Argus II enabled the 21 blind patients in a new study to locate and identify objects and people -- and even read.

About 75 percent of blind patients given these new bionic eyes were able to correctly identify single letters. More than half of those with Argus II were able to read four-letter words.

Approximately 1.5 million people around the world and about 100,000 Americans are affected by the inherited disease retinitis pigmentosa, which damages the eyes' photoreceptors -- cells at the back of the retina that perceive light patterns and pass them on to the brain in the form of nerve impulses.

The brain takes these impulses and interprets them as images. Retinitis pigmentosa causes gradual loss of these light-sensing cells and potentially blindness.

Breakthroughs like the Argus II are also critical in pushing innovation that may help those with visual impairment due to other causes. For example, in the military there were 182,525 ambulatory and another 4,030 hospitalized eye injuries reported between 2000 and 2010.

How does the Bionic Eye work?

In healthy eyes, the rods and cones in the retina, called photoreceptors, take light and turn it into tiny electrochemical impulses. These impulses are sent through the optic nerve to the brain for decoding into images.

When the photoreceptors stop working effectively, this initial conversion process fails and the brain can’t translate the light. The Argus II implant bypasses disease-damaged photoreceptors altogether.

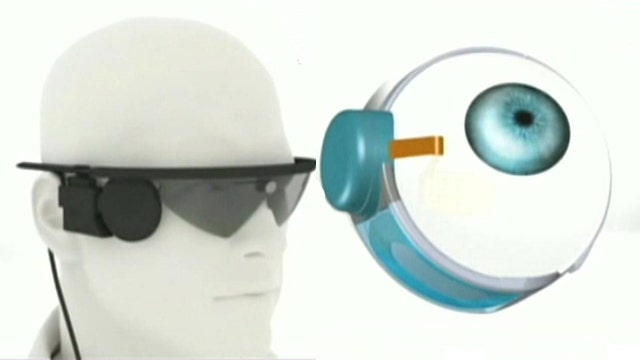

The system has three parts: a small electronic implant, a tiny camera and a video processing unit.

A small electronic device is first implanted in and around the eye. The patient then wears glasses that have a built-in video camera; it captures the surroundings and sends video to a small computer the patient wears, called a video-processing unit (VPU).

The VPU processes the video into instructions that are sent back to the glasses via a cable and then wirelessly transmitted to the implant in the eye. Electrodes there emit small electrical pulses that stimulate the retina’s remaining cells, sending the visual information along the optic nerve to the brain.

The brain perceives light patterns from this data, which patients learn to interpret -- giving them back their sight.

Beyond Bionic Eyes

There are several other promising ways to restore sight in a patient that has lost his or her vision.

According to results published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an Oxford University team has made progress in a technique that has the body rebuild the retina to restore sight.

They believe studies with mice show promise for treating people with degenerative eye disease.

In their approach, they inject "precursor" cells into the eye that create the building blocks of a retina. Within two weeks of the injections, a retina had formed.

Using this technique, totally blind mice had their sight restored and similar results had already been achieved with night-blind mice.

Meanwhile, research published in Nature by professor Robin Ali showed that transplanting cells could restore vision in night-blind mice and that the same technique worked in a range of mice with degenerated retinas.

It is hoped that eventually a doctor could put the cells in and reconstruct the entire light-sensitive layer of a human as well.

At Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, there are trials underway using human embryonic stem cells in patients with Stargardt's disease.

Early results look safe and promising, but it will take several years for it to become available.

Ballet dancer turned defense specialist Allison Barrie has traveled around the world covering the military, terrorism, weapons advancements and life on the front line. You can reach her at wargames@foxnews.com or follow her on Twitter @Allison_Barrie.