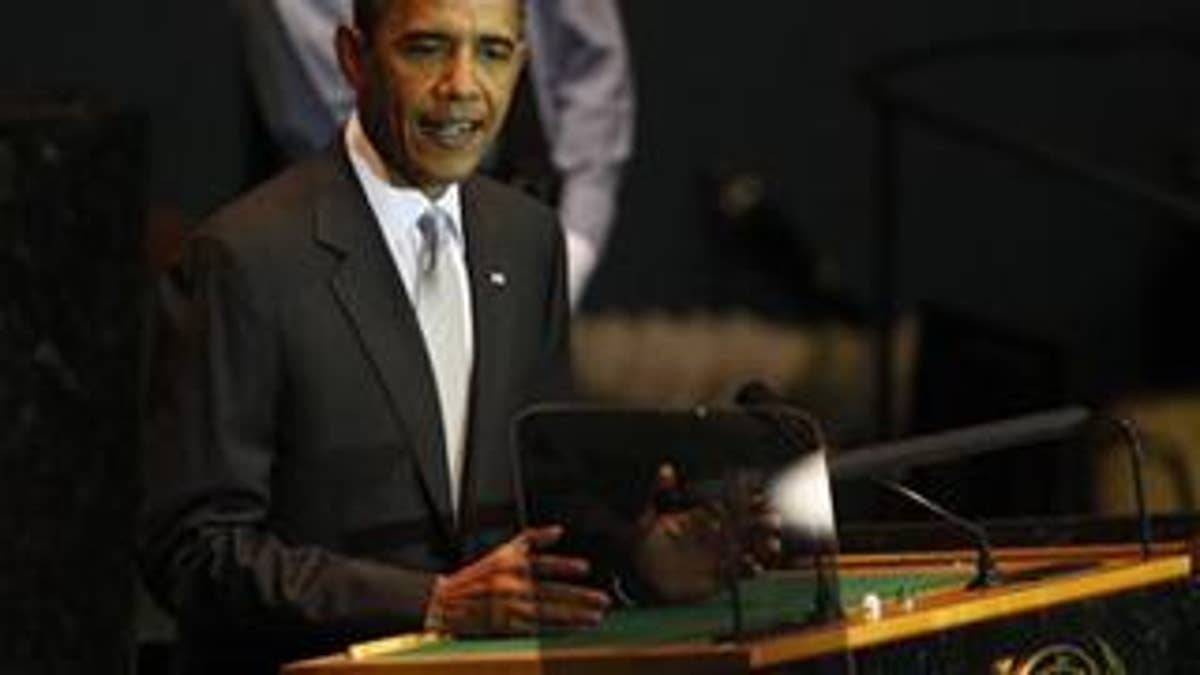

President Obama promised the United Nations Tuesday that his administration is "determined" to do more to address the nation's climate change obligations.

But left out of the speech to the General Assembly special session on climate change was the political reality the president faces in trying to keep that promise.

While the House passed a sweeping climate change bill this year, it has stalled in the Senate as health care reform dominates the domestic agenda.

Yet Obama asserted Tuesday that, while the United States was slow to respond to the global warming threat, his administration is doing more to combat climate change than any in history.

He touted progress that has been made during his term, including new standards for fuel efficiency in automobiles and the House version of the so-called cap-and-trade bill -- which he called the most important part of U.S. efforts.

"We understand the gravity of the climate threat. We are determined to act. And we will meet our responsibility to future generations," he said.

Obama warned that a failure to address the problem could create an "irreversible catastrophe." Obama said time is "running out" to fix the problem but that, "we can reverse it."

That wasn't nearly enough to blunt the criticism directed at the United States by European and Asian leaders.

He was immediately followed on stage by Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed, who criticized the West for "complacency and broken promises" on climate change.

Former President George W. Bush rejected the 1997 Kyoto Protocol for cutting greenhouse gas emissions in part because major developing nations like China and India were left out.

Now the United States is being held up as an excuse by those very countries, who question why they should make strict commitments if the United States is not doing enough.

John Bruton, head of the European Union delegation in Washington, also issued a statement ahead of Obama's speech blasting the U.S. Senate.

"I submit that asking an international conference to sit around looking out the window for months, while one chamber of the legislature of one country deals with its other business, is simply not a realistic political position," he said.

The U.S. House bill passed earlier in the year would set the United States' first federal mandatory limits on greenhouse gases. Factories, power plants and other sources would be required to cut emissions by 17 percent from 2005 levels by 2020 and by 83 percent by mid-century.

It's unclear how long Obama has to harness the Democratic majorities in Congress to push through domestic priorities like climate change legislation. Many forecasters predict Democrats will lose congressional seats in 2010, making it all the more pressing for the Senate to make progress soon.

House Minority Leader John Boehner repeated Republicans' concerns with the climate change legislation under consideration Tuesday, warning that it will cost American families hundreds extra in energy costs.

"Out-of-touch Washington Democrats don't seem to get it," he said in a written statement. "Middle-class families and small businesses are struggling, and they shouldn't be punished with costly legislation that will increase electricity bills, raise gasoline prices, and ship more American jobs overseas to places like China and India."

Even if the Senate passes its own version, the differences will have to be reconciled before a bill heads to the president's desk.

But Obama maintained confidence Tuesday that the United States will act and put added pressure on developing nations to do the same.

"Yes, the developed nations that caused much of the damage to our climate over the last century still have a responsibility to lead, and that includes the United States. And we will continue to do so -- by investing in renewable energy, promoting greater efficiency, and slashing our emissions to reach the targets we set for 2020 and our long-term goal for 2050," Obama said. "But those rapidly-growing developing nations that will produce nearly all the growth in global carbon emissions in the decades ahead must do their part as well.

"They will need to commit to strong measures at home and agree to stand behind those commitments just as the developed nations must stand behind their own. We cannot meet this challenge unless all the largest emitters of greenhouse gas pollution act together," he said, adding that wealthy nations have a responsibility to help developing nations financially to make the changes.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.