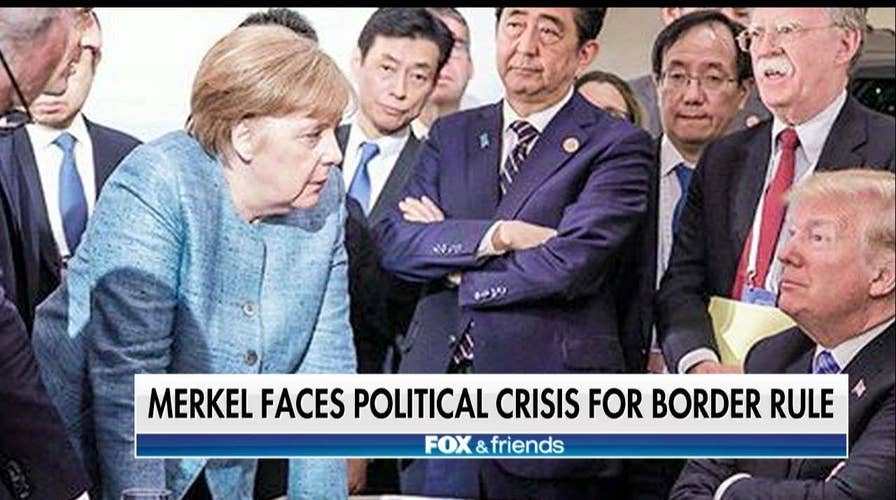

The German government almost collapsed this week. At the heart of it all: a dispute over immigration policy.

On one side was Interior Minister Horst Seehofer, head of the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) Party. His support is crucial to maintaining Chancellor Angela Merkel’s coalition government.

Seehofer wants Germany to start turning away migrants and refugees at the border. But Merkel is the godmother of the European Union’s immigration policy. She worries about the impact the Seehofer policy would have on the rest of the European Union.

The political crisis has been averted, for now. Seehofer has agreed to give Merkel two weeks to negotiate a solution.

Merkel’s opening of the borders dramatically intensified the risk Germany faces from terrorism.

But the broader crisis for German society lingers on, with no easy solution in sight. At the heart of the problem is Germany’s response to the exodus of migrants from the Middle East and Africa.

In 2015, Merkel made the decision to open Germany’s borders to a mix of asylum seekers and economic migrants. She views it as an act of humanitarianism, and no doubt, lives were saved. Equally doubtless, though, is that the decision has led to lives being lost.

I recently completed a study of terrorist plots perpetrated by asylum seekers and refugees between 2014 and 2017. Particularly striking was the impact that Merkel’s asylum policies had on the threat facing Germany.

During the period I studied, asylum seekers planned 32 separate terrorist attacks. More than a third of them were to take place in Germany – making it by far the most frequently targeted country. Four of the 13 plots hatched in Germany led to either injuries or death.

Most commonly, the nationality of those planning the attack was Syrian – the country from which Germany took in so many people. Some were radicalized abroad; some were radicalized in Germany itself. One plotter – welcomed into the country in 2015 – was just 16 years old.

Clearly, Germany accepted people it should not have. But it also failed to expel bad apples quickly enough. Consider the case of a Tunisian, Anas Amri. He arrived in Italy in 2011, spent time in jail there, and then journeyed on to Germany in 2015.

Germany rejected his asylum request, but did not deport him. Amri had no passport, so Tunisian authorities refused to take him back without more proof.

In December 2016, Amri – who was in contact with ISIS commanders – commandeered a truck and drove it into a Christmas market in Berlin, killing 12 and injuring 48.

It was a similar story with Saudi-born Ahmed A, an asylum applicant from Gaza. He arrived in Europe in 2008. His request for asylum was rejected in Norway, Spain, Sweden and, finally, Germany. Despite the rejected petition, he stayed in Germany. And last July he carried out a series of Islamist-inspired stabbings in Hamburg that left one dead and five injured.

The threat Germany faces did not begin with the refugee flow. Holger Münch, head of Germany’s domestic criminal investigation agency, pointed out in March 2016 that Germany had prevented 11 attacks between 2000 and 2013.

Yet it should also be pointed out that, in 2016 alone, Germany faced a virtually identical number of plots just from asylum seekers (so that’s before we even consider homegrown radicalization).

Merkel’s opening of the borders dramatically intensified the risk Germany faces from terrorism. This helps explain why the outsider party Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) did so well in the 2017 elections, and why Merkel now has to govern in a coalition.

So far, that is as much of a political price as Merkel has had to suffer. However, as this week’s events have hinted at, that could easily change. Merkel’s future is assured for two weeks. The long-term looks far more uncertain.