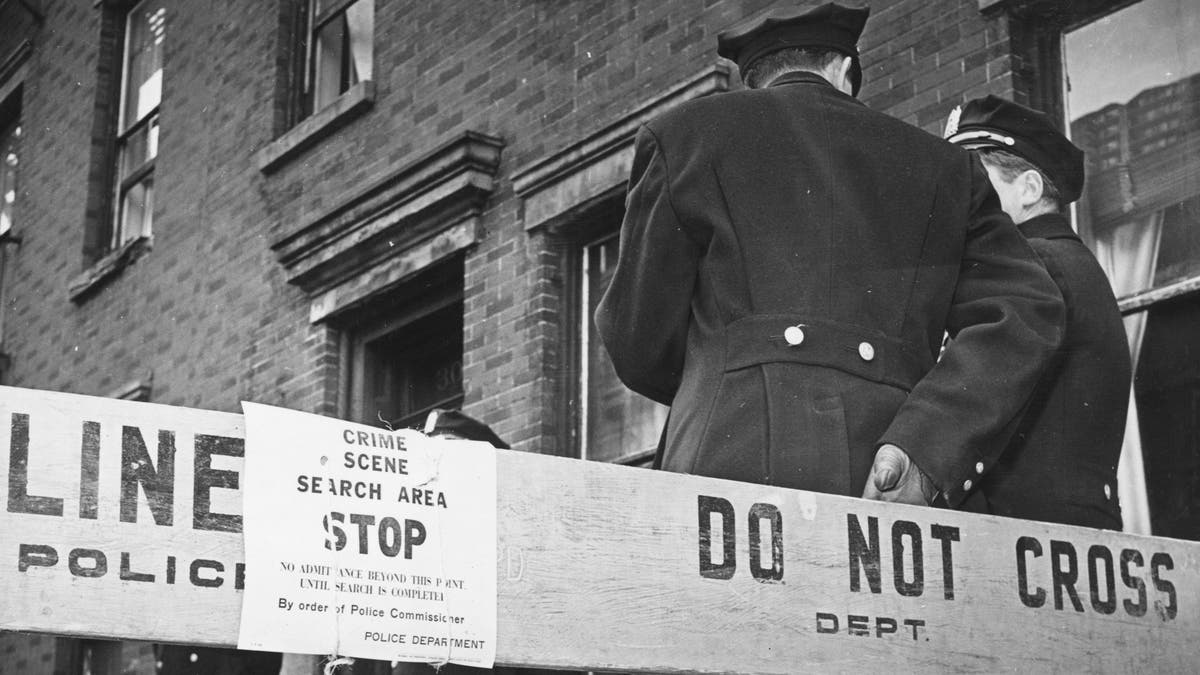

3rd March 1961: Police stand in front of the cordoned off house where 4-year-old Edith Kiecorius was murdered by Fred Thompson, in New York, USA. (Getty)

They came in behind me in the narrow alcove between the street entrance and the locked door that led into the four-story walkup apartment on East 7th Street between Avenues C and D. It was the late 1960s and this part of the Lower East Side of Manhattan aka Alphabet City was notorious as a festering cesspool of drug addicts and violent crime.

Further west, toward the numbered avenues, the area was beginning a tentative gentrification that included a new neighborhood name heavy on hope and optimism. The shopkeepers, restaurateurs and the pot-smoking flower children moving in from the suburbs and from small towns across the country called it the East Village.

Memories of the bad old days have faded, and after a generation, voters forgot. So now comes Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio; he’s an old-style liberal Democrat whose campaign centered on a promise to unshackle a city straining under the yoke of police excess.

But over where I lived, in the building where the four junkies closed in behind me that night when I was coming home from classes in Brooklyn Law School, it was still the Lower East Side. And what was about to happen to me was something that happened in that neighborhood every day, all day and night, 24/7 — a mugging.

“Open the door,” said the one closest to me, a stoned, menacing Latino not from the neighborhood maybe a year or two younger than I was. He held the jagged edge of a broken bottle against the back of my neck, his colleagues crowding into the tiny alcove behind us.

There was so little space they had to ease off to give me the room I needed to unlock the inner door. I lived on the first floor of the building. Knowing that if I let them into my apartment anything could happen, as I opened the door I bolted down the hallway, shouting to my landlady whose apartment was also on the first floor.

“Mrs. Hayes! Mrs. Hayes! Call 911! Call 911!”

There were just the two apartments per floor, the widow Mrs. Hayes’ on the left, mine on the right. I ran straight to a third doorway at the end of the hall, the mop closet, and tore it open searching frantically for something to defend myself with. There was only a mop, which I grabbed and turned to face my attackers. In the ensuing melee I never stopped calling to Mrs. Hayes to call the cops.

The guy closest to me smashed what was left of his bottle over my forehead. His buddy smashed another bottle over the back of my head. Struggling and shouting after what seemed forever but was probably 15 or 30 seconds, they ran out, carrying with them my old battered briefcase filled only with law books.

When they were gone for sure, I unlocked my apartment door, went inside and took a shower, picking the glass carefully out of the gaping wound in my forehead. Mrs. Hayes emerged tentatively after I was already out of the shower, assured me that she had called 911, and checked to see that all the glass had been picked out of the gash and the smaller wound in the back. The bored, unhurried cops from the 9th Precinct finally arrived around then. When I asked angrily what had taken them so long, they said they were busy, and advised me to get myself to Beth Israel Hospital on 17th and 2nd Avenue.

Ironically, it was the hospital I was born in. I went and got the stitches needed to close the wounds, 36 in the front, eight in the back, the scar on my forehead is still visible 45 years later.

Why do I tell this old story, almost quaint when you realize that aside from my mop the only weapons in the battle were the bottles used to crack open my head? Well, I could have told of my two decades in Alphabet City, like the four times my various apartments were burglarized or the numerous muggings, car vandalisms, robberies, murders or other scenes from ‘Once Upon a Time in New York’ that I’ve seen close-up, but you get the idea. This used to be the grittiest, most dangerous big city in the industrialized world. It is now the safest. What happened? How did we go from over 2,000 homicides a year to less than 400?

For one thing junkies don’t roam the streets like they did in those bad old days. The social safety net is more expansive and folks are not as desperate. Cops are more professional and responsive, some say aggressive, and the neighborhoods are not as raw.

Beginning with Democratic mayors Ed Koch and David Dinkins, and accelerating into the generation-long rule of Republican mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, this city became far less tolerant of criminals than it was in the days of those mean streets. Not only is the murder rate one-fifth what it was then; decent people have a reasonable expectation statistically, even in marginal neighborhoods, that they will never be the victims of violent crime.

But memories of the bad old days have faded, and after a generation, voters forgot. So now comes Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio; he’s an old-style liberal Democrat whose campaign centered on a promise to unshackle a city straining under the yoke of police excess. Vowing to undo the strict regimes of police commissioners like Bill Bratton, Bernie Kerik and especially Ray Kelly, de Blasio coasted to victory. In the rhetoric of his campaign, tactics like stop-and-frisk treated all minority men as potential suspects eroding civil rights and quality of life.

Surrounded by his accomplished wife, Chirlane McCray, a woman who happens to be black and a former lesbian (it doesn’t get any more New York), and two gorgeous children, daughter Chiara and Afro-wearing, teen heartthrob son Dante, de Blasio hammered home the message that his Republican predecessors only cared about protecting the fat cats.

It helped that his opponent Joe Lhota came across as a bland bureaucrat whose anti-crime message seemed outdated fear-mongering.

It worked. De Blasio won by historic margins, earning nearly three-quarters of the entire vote citywide; his landslide included 96 percent of black voters, which was more than a black candidate Bill Thompson got last time against Mayor Bloomberg in 2009, and 87 percent of Hispanics, which was more than Fernando Ferrer, a Puerto Rican candidate for mayor did in 2005.

So what happens now? Candidate de Blasio said he would abolish stop-and-frisk, allow a federal monitor to be imposed on the NYPD, and through various pre-school and other social programs rewrite our economic ‘Tale of Two Cities’.

It was obviously what most New Yorkers wanted to hear. His message resonated from the far corners of the five boroughs. He inspired and motivated this town like no one has done since the long ago days of Fiorello LaGuardia and the New Deal. God bless him. Now he has to govern a churning, wildly divergent world capital where 8 1/2 million restless souls compete for space, stuff and a leg up. Hopefully, Mayor De Blasio will get the point of my trip down memory lane. If people aren't safe in their homes and on their streets, nothing matters and nobody wins.