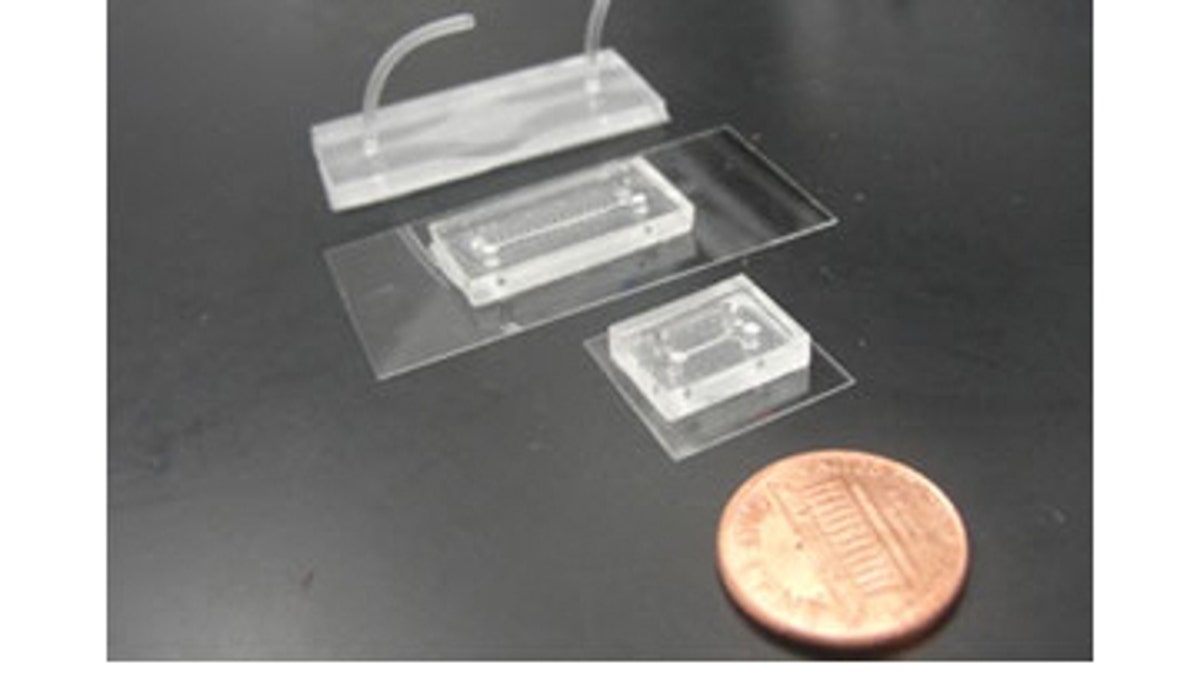

Each of these microchips contain living brain and circulatory system cells. In the future, such chips could be used to study basic brain functions and test drugs for neurological diseases. (Draper Laboratory)

A new microchip device that contains living brain and circulatory cells is designed to act like one tiny part of the human brain, leading the chip's creators to dub the device a "brain-on-a-chip."

"Our device is designed to be the most biologically realistic model of brain tissue developed in the lab thus far," Anil Achyuta, a bioengineer who led the brain-on-a-chip research at the nonprofit Draper Laboratory in Florida, said in a statement.

Unlike the microchips inside computers, cellphones and other gadgets, this brain-on-a-chip — which is made with living cells taken from rats — isn't imprinted with an electrical circuit. Instead, scientists consider it a microchip because it has a network of tiny channels inside.

Achyuta and his team hope to use the brain-on-a-chip to study important brain functions and problems, such as strokes or hardening arteries. They also hope they'll be able to use the chip to test drugs and other therapies for neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Each chip contains neurons, the brain cells that carry information, along with supportive brain cells and cells taken from the inside of rats' blood vessels. That mix of cells allows researchers to use the chip to study how the brain and the circulatory system communicate with each other, which plays an important part in many neurological diseases.

Tiny channels in the chip carry liquid between the cells, giving them the nutrients they need to live, much like flowing blood would in the brain. The channels also have another use: If scientists want to study how a drug might affect brain cells, for instance, they could pump the drug into the chip through its liquid channels.

Achyuta's team is now looking to improve the chip and to add more types of cells to it. They also plan eventually to make the chip using lab-grown human cells instead of rat cells. (Currently, human neurons for experiments generally come from other types of cells that people donate to science, which scientists transform into brain cells using chemicals. Neurons may also come from fetuses donated to science.)

The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded the brain-on-a-chip. The device is part of a larger, $26.3 million DARPA project aimed at creating small, plastic chip versions of many human organs. Ultimately, DARPA wants a system that connects several chip-organs into a "human-body-on-a-chip," which scientists can use to quickly test new drugs and vaccines.

Achyuta and his colleagues published their work in the September issue of the journal Lab on a Chip.