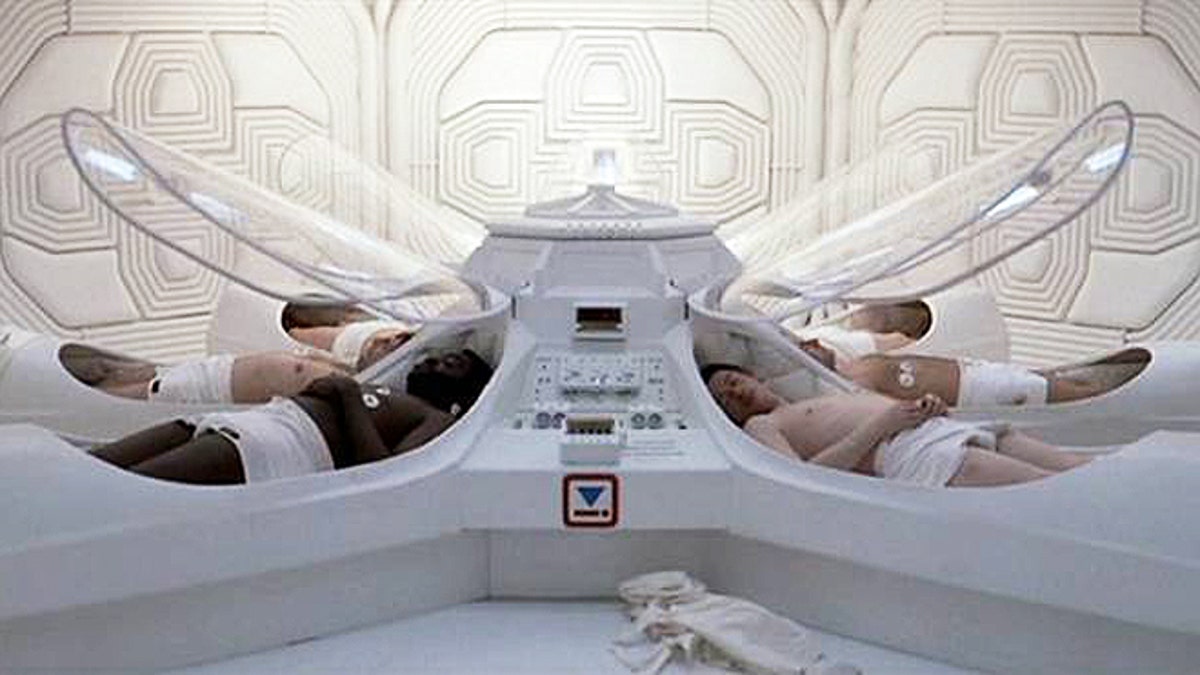

Deep-space travellers awaken from hibernation suspended animation in a scene from the 1979 film, "Alien." (20th Century Fox)

Is hibernation the solution not just to interstellar travel but to battlefield trauma?

New research aims to study the use of hibernation to stabilize soldiers for transport to medical facilities. And black bears are the guinea pigs -- human-sized hibernators to help scientists better understand hibernation’s fundamental molecular and biological functions.

So far, most research has focused on small mammals such as hedgehogs and black squirrels, which reduce their body temperature to their freezing point for weeks, interspersed with occasional breaks when the body temperature rises to normal for approximately a day.

Black bears have a similar winter habit, and they’re of particular interest because researchers believe their system of metabolic suppression could be applied to humans in emergency situations.

While humans lose bone and muscle during a period of inactivity, bears do not seem to incur this problem. Scientists believed these breaks provide an opportunity for nerves to repair any damage due to the hibernation itself.

By working out the biochemical pathways to prepare, enter and recover the hibernation phase, some researchers believe they may be able to create pharmaceuticals for humans that can induce and reverse such a state.

They envision a cutting-edge medical intervention that could boost survival rates following acute traumatic hemorrhage, or significantly improve recovery and rehabilitation from traumatic muscle and bone injury.

A new study from scientists with Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) and the University of Alaska Fairbanks may make it possible.

In the study, five American black “nuisance” bears were captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and set to hibernate for five months in mimicked dens away from human interaction. The dens were equipped with remote sensing devices like infrared cameras and activity detectors.

It’s the first time a team has succeeded in continuously measuring black bear metabolic rates and body temperatures while hibernating during natural winter conditions as well as during the spring after they leave their dens.

Previously, technical limitations have prevented the long-term monitoring of animals as large as black bears.

Radio transmitters were implanted to record the bears’ heartbeat and muscle activity. Their metabolism was measured by studying the concentration of oxygen and carbon dioxide going in and out of the den.

Typically, for each body temperature drop of 10 degrees Celsius, an animal's metabolism slows to about half. This team revealed that black bears can slow their metabolism to 25 percent while maintaining a core body temperature drop of only five or six degrees.

During hibernation, the bears’ heart rates slowed to 14 beats per minute from about 55; and they breathed only once or twice a minute.

Most small hibernators automatically return to a normal state upon leaving their dens in the spring, but the team discovered that it took black bears two to three weeks to stabilize their metabolisms, despite a rapid normalization of body temperatures. They hope to learn whether hibernation can happen during the summer too.

Two million dollars have gone into researching “hibernation genomics” -- the study of the genes associated with hibernation. And the potential versatility of this research is reflected in the range of support from the office of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association and the National Science Foundation.

Indeed, cracking hibernation could even drive new medicines to prevent osteoporosis and muscle atrophy, they hope.

It also holds promise for rapidly reducing “metabolic demand” in heart attack or stroke victims by putting them in a protected stabilized state buying more time to move them to medical care.

As for those interstellar spaceships, don’t hold your breath. Unless you’re a bear.