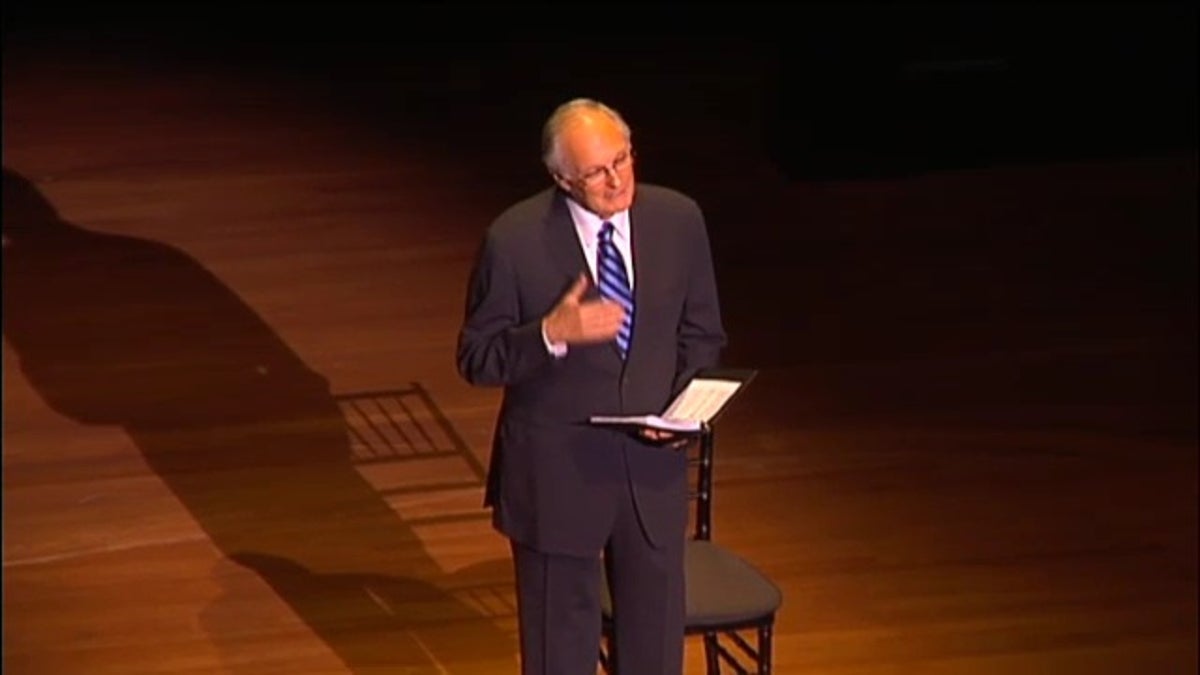

June 1, 2011: Alan Alda, the long-time host of the PBS show "Scientific American Frontiers," discusses the debut of his play about the life of Marie Curie at the 2011 World Science Festival. (FoxNews.com)

Most places one would look for a scientist include classrooms, laboratories, and lecture halls. And now they can be found in one more location – on stage.

As part of the 2011 World Science Festival, actor Alan Alda explained to festival attendees at the Paley Media Center the necessity for scientists to learn skills that most actors possess. Alda described that talents such as listening and personalization help researchers to better explain their studies with clarity -- and not alienate the general public with esoteric language.

Alda referenced his eleven years experience hosting the PBS show “Scientific American Frontiers” helping him to discover the need for scientists to have better communication skills.

During his tenure on the show, Alda interviewed over 700 scientists.

“They weren’t really interviews, they were conversations,” Alda told the audience. “That was something we sort of invented on the show – a different way to do a science program, which was to have somebody who didn’t know all that much – that was the part I played – and to have that person who was nevertheless extremely curious about what scientists did and how they did it, and put those two together in a conversation."

To demonstrate the effect improvising skills have on scientists, Alda had conducted a mini experiment about a year ago with a group of graduate and PhD students at New York's Stony Brook University. First he had them explain their research to an audience. Then, after 3 hours of improvisation classes, he had them address that audience again. A video of the session showed the significant transformation of the students’ dialogue and body language.

“They not only improvise as freely as before, but they’re interactions with the audience are getting more and more intimate,” Alda said of the students, who have continued taking improvisation classes over the past year. “It’s thrilling to see them.”

Alda then brought the students on stage, and the rest of the event was spent playing improv exercises. The games include anything from passing around an imaginary object to acting out a scene of picking up a distraught hitchhiker. The audience was even included on a few of the games, making the show interactive and comical.

At the end of the event, both the students and Alda agreed that the skills they gathered from class have helped them to better communicate with those unfamiliar with their work, as well as people in general.

“When they talk to the public, they can transfer that sense of intimacy to the public and relate to them as if they’re talking to one another on stage,” Alda said. “It does carry over.”