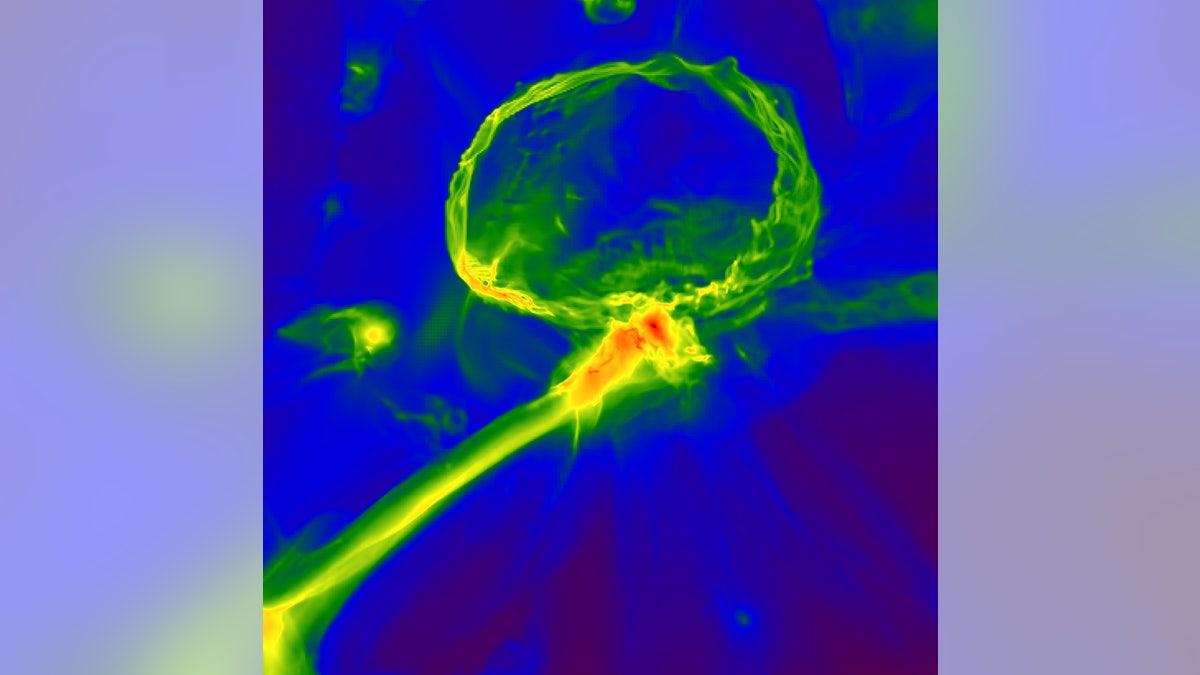

Snapshot from a simulation of the first stars in the universe, showing how the gas cloud might have become enriched with heavy elements. The image shows one of the first stars exploding, producing an expanding shell of gas (top) which enriches a nearby cloud, embedded inside a larger gas filament (center). The image scale is 3,000 light-years across, and the color map represents gas density, with red indicating higher density. (Britton Smith, John Wise, Brian O’Shea, Michael Norman, and Sadegh Khochfar)

An ancient cloud of gas many billions of light years from Earth may contain the signature of the very first stars that formed in the Universe.

The gas cloud, discovered by a team of American and Australian scientists, has an extremely small percentage of heavy elements, such as carbon, oxygen and iron – less than one thousandth the fraction observed in the Sun. It was discovered, using the Very Large Telescope in Chile, as it was 1.8 billion years after the Big Bang.

Related: Stars in distant galaxies found to have a pulse

“Heavy elements weren't manufactured during the Big Bang, they were made later by stars,” Neil Crighton, the lead researcher from Swinburne University of Technology’s Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, said in a statement. “The first stars were made from completely pristine gas, and astronomers think they formed quite differently from stars today.”

Soon after forming, these first stars – also known as Population III stars – exploded in powerful supernovae, spreading their heavy elements into surrounding pristine clouds of gas. As a result, those clouds carry a chemical record of the first stars and their deaths – allowing scientists to read it like a detective would a fingerprint.

Related: Astronomers find most distant object in solar system

“Previous gas clouds found by astronomers show a higher enrichment level of heavy elements, so they were probably polluted by more recent generations of stars, obscuring any signature from the first stars,” Crighton said.

“This is the first cloud to show the tiny heavy element fraction expected for a cloud enriched only by the first stars,” co-author Swinburne’s Professor Michael Murphy added.

The next step is finding more of these systems that would allow the researcher to measure the ratios of several different kinds of elements.

Related: Rare galaxy found with 2 black holes - one starved of stars

“We can measure the ratio of two elements in this cloud - carbon and silicon. But the value of that ratio doesn't conclusively show that it was enriched by the first stars; later enrichment by older generations of stars is also possible,”said John O’Meara, of Saint Michael’s College in Vermont and a co-author on a paper describing the findigns that will appear in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters on Jan. 13.

O'Meara presented the results at the American Astronomical Society meeting on Friday.

“By finding new clouds where we can detect more elements, we will be able to test for the unique pattern of abundances we expect for enrichment by the first stars,” O’Meara said.