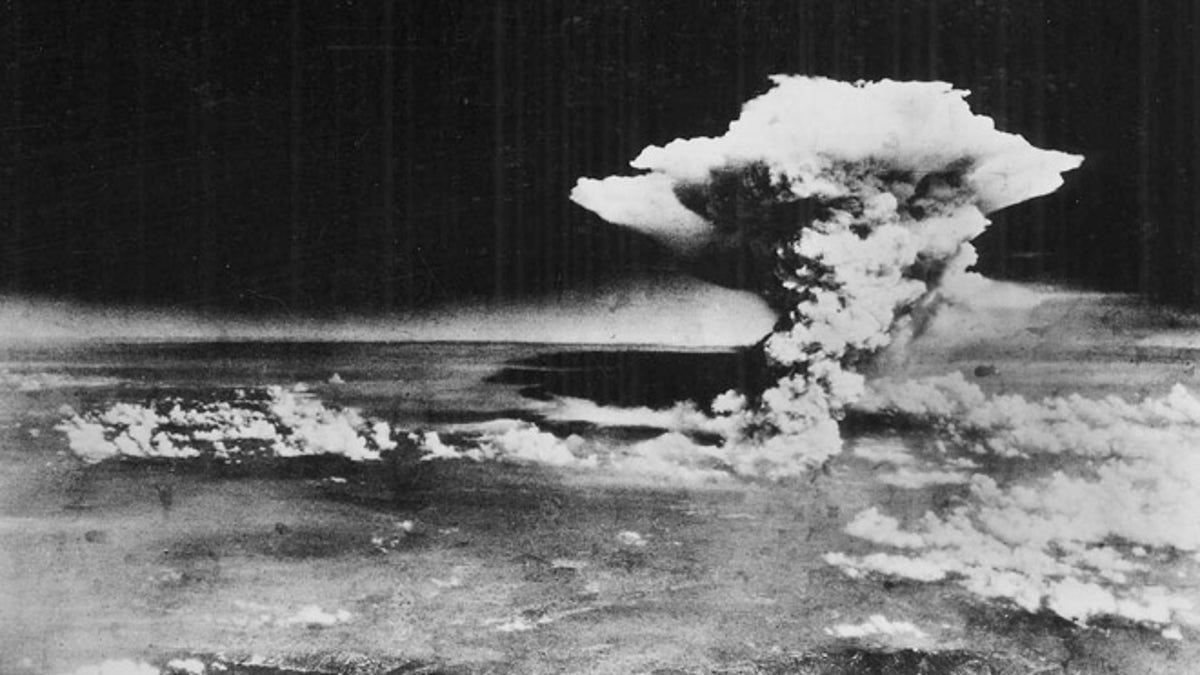

FILE Aug. 6, 1945: Photo released by the U.S. Army, a mushroom cloud billows about one hour after an atomic bomb was detonated above Hiroshima, western Japan. (AP)

Seventy years ago on July 16, scientists with the Manhattan Project tested the Trinity gadget—the first atomic bomb—in the desert outside of Alamogordo, NM. The pre-dawn flash of light that mimicked the noonday sun lit the surrounding mountains, illuminating the imminent end of World War II; it also signaled that humanity had entered a new Atomic Age that held great promise as well as great challenges ahead.

The Trinity test was arguably among the greatest scientific and engineering achievements of the 20th Century. By assembling a collection of the greatest minds in the world, Los Alamos—along with the laboratories at Oak Ridge, TN, and Hanford, WA—created a bold model for multidisciplinary technical innovation. It is a model that Los Alamos and the 16 other national Laboratories under the U.S. Department of Energy sustain today.

Since Trinity, Los Alamos has continued as an essential national-security science laboratory. Like their predecessors in the Manhattan Project, Los Alamos researchers help solve the nation’s most difficult national-security challenges. From Trinity to today, Los Alamos’ core mission remains ensuring the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nation’s nuclear deterrent, which many believe has helped prevent another global conflict. This challenge requires scientific excellence spanning nearly every discipline. The power of multidisciplinary science has been key to Los Alamos’ success for the past seven decades.

In the years beyond Trinity, when other nations began testing their own nuclear arsenals, Los Alamos expertise again came to the fore to help monitor the activities of other nations to help ensure that promises made under the Limited Test Ban treaty, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaty, the Strategic Arms Reduction treaties, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, and others like them were honored. Scientific expertise from Los Alamos and elsewhere helped develop a network of satellites, sensors, and other technologies to ensure that nuclear ambitions on the part of any nation or individual would not go unnoticed. This vital service continues today.

In September 1992, the United States conducted the Divider nuclear test. Since then, there have been no additional U.S. nuclear tests. Cessation of testing created a challenge perhaps even greater than development of the original atomic bomb. Nuclear weapons are incredibly complex, and many of their components are in a radioactive environment. Over time, plastics crack, materials suffer defects, and certain components reach the end of their engineered lifespan. In the absence of testing, our nation was faced with challenging questions about the safety, security, reliability, and effectiveness of its nuclear deterrent.

To address these questions, research teams at Los Alamos and its sister laboratories again turned to multidisciplinary science. During the past 20 years of science-based stockpile stewardship, our nation’s top scientists have employed advanced computing techniques and modern experimental facilities to maintain confidence in certification of our deterrent.

Multidisciplinary science has proven beneficial in other areas as well. In our vigilance to detect clandestine nuclear tests, Los Alamos researchers also discovered previously unknown natural phenomena that have helped us better understand our universe and protect satellites from the ravages of cosmic radiation. Computer and mathematical modeling techniques perfected at Los Alamos help keep tabs on pandemics, make off-shore oil rigs safer, and helped create a possible vaccine against HIV. Laser technology originally developed to detect nuclear materials here on Earth is now aboard the Curiosity rover to help NASA characterize the surface of Mars.

Los Alamos makes the world a safer place by providing expertise and technology to help thwart a growing list of security concerns, including terrorism, nuclear proliferation, cybersecurity, energy security, and much more.

National laboratories like Los Alamos endure because our nation has made the wise decision to use agile multidisciplinary science teams as a hedge against global uncertainty. As long as our national laboratories exist, they can continue to serve our nation and help address its greatest challenges. Though the world has seen many changes since Trinity, one thing has remained constant: Los Alamos remains essential to our nation’s security.

Dr. Charles F. McMillan is Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory.