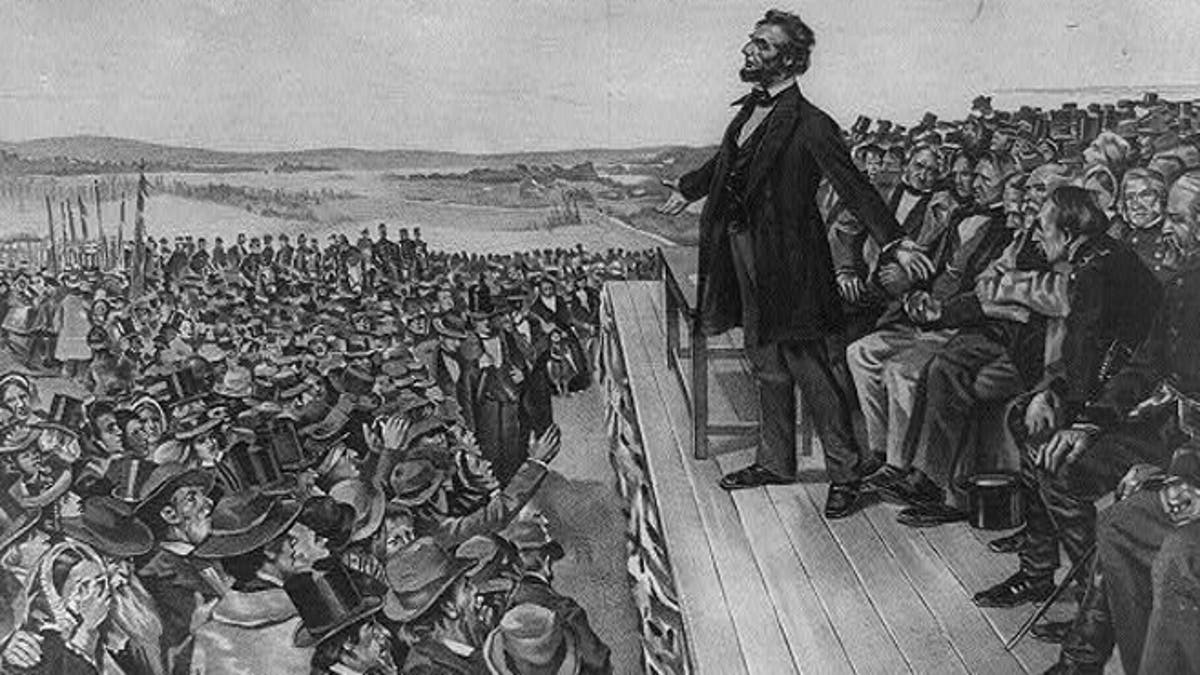

(Library of Congress)

1787: Americans are thunderstruck. After secret meetings, political muckamucks have proposed a breathtakingly radical new government. Tempers flare over how to respond.

1861: a meltdown over slavery. Neighbors — sharing the same heritage, language, and God — kill and die in droves.

The New Deal. Civil Rights. Today’s skirmishes on spending. Americans can’t seem to agree on what their government be empowered to do.

[pullquote]

You would think the United States has a split personality.

You would be right.

Abraham Lincoln grieved over this. Delivering the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863 — 150 years ago — he was striving to coax one of America’s dueling personalities to conclusively dominate the other.

America suffers this split personality because it was founded by not one but two different documents: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

We idly regard these documents are harmonious. But they are profoundly incompatible. The turbulence between them made the Civil War inevitable, and has perpetually stoked partisan fires.

Read the Declaration of Independence. Does it form one nation? No. It decrees Georgia, Maryland, Connecticut and the rest “free and independent states.” The Declaration fundamentally advocates small government and states’ rights. It wants weak, local power — instantly answerable to the people. And the Declaration calls rebellion a patriotic duty.

The Constitution harkens to big government. Unifying the states, it massively demotes their influence. And in the Constitution, rebellion is treason.

Consider further: the Declaration says men are created equal. But the antebellum Constitution sanctioned human bondage.

Slavery. States’ rights. Government power. Rebellion. There’s your whole Civil War, 74 years before the first shot.

In 1861, the Union and the Confederacy sought to demonstrate themselves the truest expression of American values. But to do so, each had to cherry-pick from America’s discordant founding documents.

The Confederacy, casting itself the successor of tyranny-toppling 1776, appropriated the Declaration’s notion of rebellion. But “rebels” rejected its pronouncement on equality. They demanded to hold human beings as property — as the Constitution had always permitted.

The Constitution created the Union. Yet it’s foremost an apparatus to establish, provide, insure, promote, and secure ends the states desired. That pragmatism actually favored the Confederacy. For if the Union is merely a marriage of convenience, why shouldn’t it be severable in peaceful divorce?

Lincoln, tasked with proving that America was rooted in far deeper soil, turned to the Declaration’s lyricism.

The Gettysburg Address is the resulting basket of Lincoln’s picked fruit.

Lincoln plucked from the Declaration a poison apple to use against slavery: his phrase that America was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” But he likewise drew from Constitutional ideas. Five time he rolls out the term “nation” to assert that the states had irreversibly consolidated in 1788. The vow to safeguard “government of the people, by the people, for the people” signals Lincoln’s intention to bring to bear every weapon Article II reserves him.

Did the Gettysburg Address persuade Confederates to switch sides? Hardly. But it reenergized Republicans. — both during the war and, by its veneration and repetition, for decades afterwards.

The triumph of Lincoln’s ideas allowed us to settle some of our founding disparities. Slavery was purged forever. Secession was remanded to extraordinary circumstances as outlined in the 1869 Supreme Court decision Texas v. White — not some regional tantrum over an election’s outcome.

The Gettysburg Address proves that a mastery of our first principles can jolt America forward.

Maybe in some future rhetorical work someone may write as potently as Lincoln. Perhaps our irreconcilable founding documents can be synthesized to finally settle the government power issue. That disparity has proved most tenacious of all.