The most important lesson of Margaret Thatcher's legacy

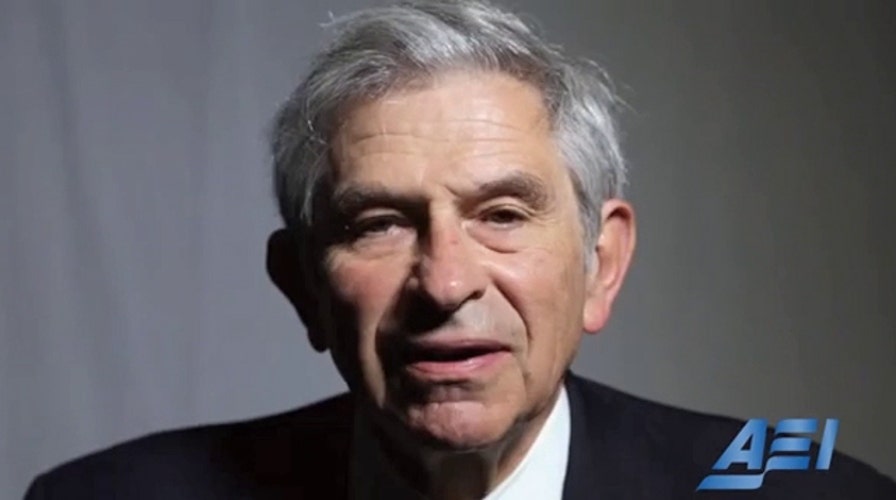

Paul Wolfowitz on how the 'Iron Lady' made her mark on history

The similarities between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are remarkable. Together they made an invaluable team that changed the course of history at a critical period.

Both were strong leaders who were not afraid to swim against the tide of easy popularity and unconcerned when their adherence to principle was dismissed as ‘simplistic’ by people who thought themselves more sophisticated.

Neither came from a privileged background, and both understood the people whom they were leading.

Both were strongly -- some said stubbornly -- principled, but flexible when it made sense to be, most notably in recognizing early in Mikhail Gorbachev a potential partner that they “could do business with,” as the Iron Lady famously put it.

[pullquote]

Both led dramatic turnarounds in the economic fortunes of their countries, after inheriting economies that were in near-crisis. And most importantly, together they helped bring about the end of the Cold War, a transformation in international relations that gives them a permanent place in world history.

But Margaret Thatcher was no mere carbon copy of her American counterpart; and it wasn’t only the fact that she was a woman, leading formidably in a male-dominated arena.

She also wasn’t the leader of a superpower. But under her leadership Britain punched far above its weight.

One of her finest moments came when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. A weaker leader might have dismissed the effort to liberate a seemingly insignificant territory 8,000 miles away as militarily hopeless and politically imprudent.

Acting largely on her own, but fortunately with the strong backing of President Reagan, Mrs. Thatcher reversed Argentina’s act of aggression. As she said to President George H.W. Bush on the occasion of receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, “The decision to use force is not easy to take. . . . Like you, Mr. President, I hate violence. And there's only one thing I hate even more -- giving in to violence. . . . The sanction of force must not be left to tyrants who have no moral scruples about its use."

Her action also led to the Argentine people removing their own military dictators, the first of a wave of peaceful democratic transitions in Latin America over the next ten years that quietly transformed the region.

I was fortunate to be able to accompany President George H.W. Bush to NATO’s first post Cold War summit. I remember Prime Minister Thatcher opening that meeting in London on July 5, 1990, saying with irony that was missed by some, “We are at a turning point in Europe's history, a turning point which is as full of promise as was 1919 and 1945.” Her own deep sense of history told her to be cautious about assuming that the end of a great conflict, even one as long and momentous as the Cold War, meant the end of all conflict.

That caution proved prescient less than a month later, on August 2, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

By a fortunate accident, the President and the Prime Minister were both attending a conference in Aspen and they came to an agreement -- as President Bush put it a few days later -- that this aggression “must not stand.”

It is commonly but mistakenly said that it was on this occasion that Mrs. Thatcher cautioned the American President not “to go wobbly.” In fact, that comment was made in the context of a very tactical question of whether to stop and board one of the first oil tankers coming out of Iraq.

On the larger strategic question of whether Saddam’s aggression had to be reversed and Kuwait liberated, I never saw President Bush’s resolve waver. But it certainly helped him to have such a stalwart person leading our closest ally.

Where Mrs. Thatcher’s influence might have made an historic difference was when it was sorely missing. With her leadership challenged by members of her own party -- partly over her reluctance to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism -- she was forced to resign as Prime Minister on November 28, 1990. As a result, she was no longer involved when the ceasefire suspending hostilities with Iraq was prematurely concluded after the 100-hour ground offensive of Desert Storm.

On the first anniversary of the invasion she said that Iraq should have been forced to “hand over Saddam Hussein for international trial as a condition of a Gulf War ceasefire. I think it would have been possible to have got that . . . because I think the Iraqis would have had no alternative." A few years later she told an interviewer that the war had been “stopped, rather too soon” and that the long-term lesson was to “complete the task to which you put your hand.” She didn’t think “that it was necessary to go onto Baghdad,” but the failure to thoroughly defeat the dictator and to abandon the Shia and the Kurds had been a mistake.

Although Thatcher was characteristically gracious, acknowledging that she was commenting on deliberations “to which I was not privy” and that there “may have been some confusion about the information they were getting as “often happens during wartime,” it seems quite clear what her advice would have been had she still been Prime Minister at the time.

Had President Bush been able to follow that advice -- as some of his comments at the time suggested he had an inclination to do -- history might have been very different and we might have been spared a second and more costly war.

But Prime Minister Thatcher had a lighter side as well, so perhaps this tribute should end on a less solemn note, with an anecdote related by the late Christopher Hitchens.

Shortly after Thatcher had been elected party leader, Hitchens, who had presciently predicted her political rise and rather audaciously described her as “surprisingly sexy,” was introduced to her at a party. As Hitchens describes the occasion in his memoir:

“Almost as soon as we shook hands . . , I felt that she knew my name and had perhaps connected it to the socialist weekly that had recently called her rather sexy. While she struggled adorably with this moment of pretty confusion, I felt obliged to seek controversy and picked a fight with her on a detail of Rhodesia/ Zimbabwe policy. She took me up on it. I was (as it chances) right on the small point of fact, and she was wrong. But she maintained her wrongness with such adamantine strength that I eventually conceded the point and even bowed slightly to emphasize my acknowledgment. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Bow lower!’ Smiling agreeably, I bent forward a bit farther. ‘No, no,’ she trilled. ‘Much lower!’ By this time, a little group of interested bystanders was gathering. I again bent forward, this time much more self-consciously. Stepping around behind me, she unmasked her batteries and smote me on the rear with the parliamentary order-paper that she had been rolling into a cylinder behind her back. I regained the vertical with some awkwardness. As she walked away, she looked back over her shoulder and gave an almost imperceptibly slight roll of the hip while mouthing the words: ‘Naughty boy!’”

A woman of iron indeed -- and with a wicked sense of humor.