Niger ambush killed four US soldiers: Timeline of what we know

As questions continue to mount about the Niger firefight that killed four U.S. soldiers in early October, here’s a timeline on what happened based on new details from the Department of Defense.

There were multiple things to blame for the October ambush in Niger that left multiple U.S. service members dead, including insufficient training and preparation as well as the team’s deliberate decision to go after a high-level Islamic State group insurgent without proper command approval, the Pentagon has said.

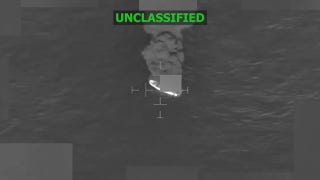

Four U.S. soldiers were killed in October 2017 by Islamic militants who attacked their convoy in Africa with rocket-propelled grenades and heavy machine guns. The body of one soldier was not found for two days.

The Pentagon’s report, released on May 10, took three months to complete, spokeswoman Dana White said in a statement. Defense Secretary James Mattis found “institutional and organizational issues, not isolated to this event that must be addressed immediately by the Department of Defense,” she said.

“However, no amount of investigation or corrective action will ease the agonizing grief that the families of our fallen must feel,” White said. “The Department hopes that the families will take pride and comfort in knowing – as this investigation makes clear — that their loved ones fought and died bravely in defense of our Nation, its people and the values we hold dear.”

From President Donald Trump’s calls to the families of the deceased to the White House’s delayed response to the ambush, details about the attack have drawn intense scrutiny and criticism. Read on for a look at what happened in Niger.

Who were the Americans killed?

Sgt. La David Johnson, 25; Staff Sgt. Bryan Black, 35; Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Johnson 39; and Staff Sgt. Dustin Wright, 29, were killed in the attack.

The bodies of some of the Americans killed were recovered by a U.S.-contracted helicopter, a U.S. official previously told Fox News. Sgt. Johnson's body wasn't found until two days after the attack as he and some Nigerien soldiers were separated from the others during the battle, the Pentagon said.

According to the report, the four killed “gave their last full measure of devotion to our country and died with honor while actively engaging the enemy.” It said none were captured alive by the enemy and all died immediately or quickly from their wounds.

What did the Pentagon say happened?

The Pentagon’s summary lays out a confusing chain of events that unfolded on Oct. 3-4, ending in a lengthy, brutal firefight as 46 U.S. and Nigerien forces battled for their lives against more than 100 enemy fighters. Amid the chaos, the report identified repeated acts of bravery as the outnumbered and outgunned soldiers risked their lives to protect and rescue each other during the more than hour-long assault.

Military officials found that the U.S. forces didn’t have time to train together before they deployed and did not do pre-mission battle drills with their Nigerien partners. And the report found that there was a lack of attention to detail and lax communication about missions that led to a “general lack of situational awareness and command oversight at every echelon.”

According to the report, the Army Special Forces team left their camp on Oct. 3 to go after an Islamic State leader who was suspected of involvement in the kidnapping of an American aid worker. But the team leader and his immediate supervisor submitted a different mission to the higher command, saying they were going out just to meet tribal leaders. That less-risky mission was approved, and when the team got to the location, the insurgent wasn’t there.

Senior commanders, unaware of the team’s earlier actions, then ordered the troops to serve as backup for a second team’s raid, also targeting the leader. That mission was aborted, however, when weather grounded the second team. The original group was then ordered to another location to collect intelligence on the insurgent, which they did without problems.

It was on their way back to the home base when they stopped for water at the village of Tongo Tongo, about 120 miles north of Niger’s capital. There, the group was ambushed by Islamic State-linked militants armed with rocket-propelled grenade launchers and small firearms.

The Pentagon said it could not conclude that the village “willingly (and without duress)” aided and supported the militants in the attack.

What else should you know?

The report included multiple recommendations to improve mission planning and approval procedures, re-evaluate equipment and weapons requirements and review training that U.S. commandos conduct with partner forces.

Mattis has directed Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, head of U.S. Africa Command, to take immediate steps to address shortfalls and has given senior leaders four months to complete a review and lay out a plan for additional changes.

Why were troops in Niger?

U.S. forces have been in Niger for more than 20 years and a joint special operations task force was created by the U.S. in 2008.

In 2011, U.S. and French forces set up a counterterrorism force in the country, led by the French, with 4,000 troops and 35,000 Nigerien troops. There were 800 U.S. troops in Niger and 6,000 U.S. troops within 53 countries in Africa, Gen. Joe Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said last year.

But the presence of American soldiers in Niger reignited a debate about the Authorization for Use of Military Force – a public law enacted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. At issue is whether the law gives the president the authority to take action against all terrorist organizations, not just Al Qaeda and the Taliban.

What was the White House's response?

The White House has been widely criticized for its response to the attack – especially in the delay in acknowledging the ambush.

President Trump, too, was criticized for his public feud with a Democratic congresswoman and Sgt. La David Johnson’s widow. Rep. Frederica Wilson, D-Fla., accused Trump of making “insensitive” remarks to Myeshia Johnson.

Trump has denied Wilson’s allegations, but the mother of the deceased soldier has backed up Wilson’s claims.

White House chief of staff John Kelly said he was "heartbroken" that Wilson used the conversation she overheard to attack Trump. Kelly, whose Marine son died in Afghanistan, added that the president did the best he could in the situation.

Because of the White House’s response to the attack, it’s been called “the president’s Benghazi” by some Democrats, referencing the controversial attack in 2012 that left four American service members dead.

Fox News' Lucas Tomlinson and The Associated Press contributed to this report.