US mulls more aggressive role in Afghanistan

Former special operations intelligence analyst Brett Velicovich explains

ARLINGTON, Va. – They have been the backbone of U.S. efforts in the Afghanistan war and subsequent reconstruction of the nation.

They were translators for U.S. soldiers; they were diplomats in American embassies and military bases; some even worked as intelligence officers who helped fight the drug trade and terrorism. Their work put them in certain danger from the Taliban and ISIS, but luckily they were eligible for the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) — a program that allowed those who provided service to the U.S.

The SIV program lets applicants, their spouses and children under 21 years of age to take up residence in the U.S. and also apply for a green card.

But for many of these people, getting to the U.S. was only half the battle.

Many of those who have arrived in the U.S. for a chance at a better life are discovering a whole new set of hardships as they adjust to life in America.

This month alone, a total of 15 families -- which includes 45 children -- who arrived here on the SIV are in danger of being evicted from their homes in the Washington, D.C., metro area, according to No One Left Behind, an organization that focuses on helping SIV recipients and their families. Many of these families arrive with little or no money.

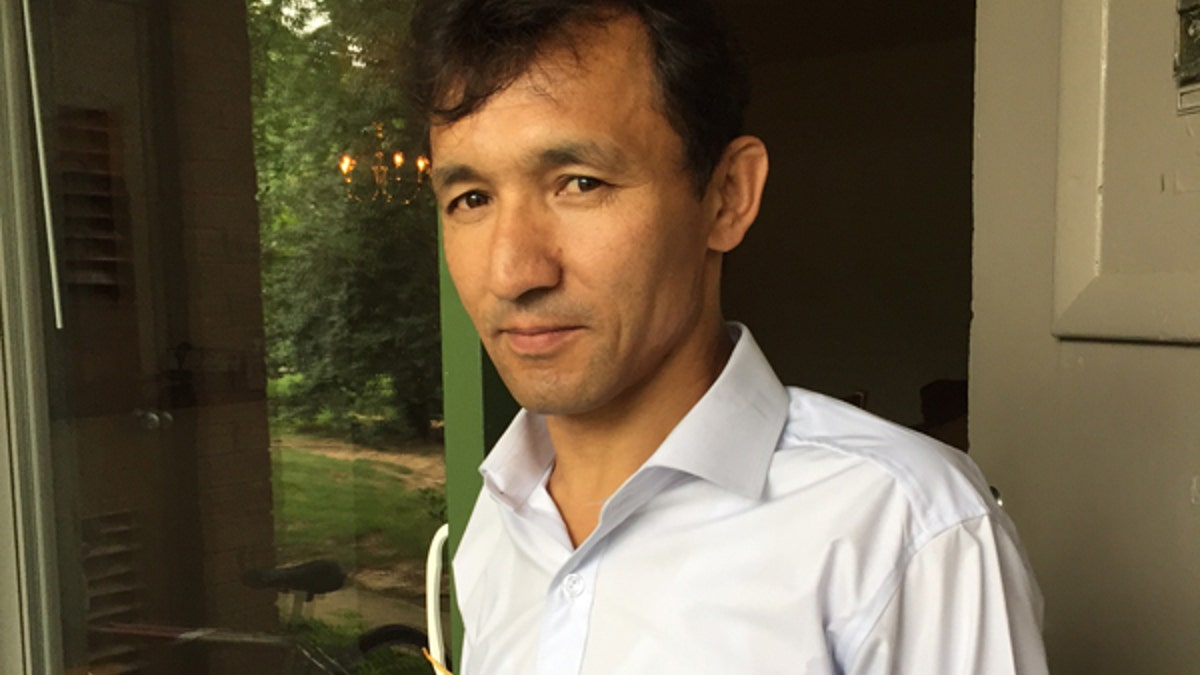

Mohammad Yahya Aslamyar said that he was eligible for the SIV for quote some time, but did not choose to leave until a friend was abducted by the Taliban. (Fox News/Perry Chiaramonte)

They also find it difficult to navigate the American job market. While most have stellar qualifications, experience and education, it’s often not accepted here as valid credentials, leaving many of these new citizens, to take menial jobs in retail or service industries.

The pay is often not enough to cover the rent.

“Your experience is not valid here. Your education is not counted," Mohammad Yahya Aslamyar, an Afghani national who arrived in Northern Virginia in April and lives in an apartment with his wife and two young children. “You feel like you were someone hit with a hammer in [the] head.”

Aslamyar worked with U.S. Agency for International Development’s reconstruction efforts as an auditor and compliance officer and even helped to build the office structure of the U.S. Embassy. The work was vital, but it put him and his family in danger.

“My friend asked me to leave [Afghanistan],” he said. “I had Taliban members tell me that they would report me to ISIS. It put a lot of us in danger. As time passed, the condition got worse.”

Aslamyar said that he had been eligible for the SIV for some time but originally did not choose to leave. His mind was changed after a friend and colleague was abducted by the Taliban and beaten and interrogated.

“You don’t want to leave your family in danger,” he said. “If they found me, they would have killed me.”

Aslamyar is grateful for the safety he and his family are now afforded by being in the U.S., but they are having trouble making ends meet.

He has been unable to find work and has been forced to scrap together whatever cash he can from donations or friends within the large SIV community that has developed in Alexandria over the past several years.

“Your experience is not valid here. Your education is not counted."

“If I was alone I would be OK, but with a family, it is hard to manage,” he said.

Aslamyar recalled a time when he went for assistance at the county hall in Alexandria and how poorly he was treated by one of the clerks.

“I brought my resume and my credentials from Afghanistan. She told me it didn’t matter,” he said. "She told me, ‘You start from zero. You are nothing here.’”

Despite hitting roadblocks in the search for a job, Aslamyar, is optimistic that he will be able to provide for his family. Even if he has to work his way up from the bottom.

“I am the luckiest person. I was able to save my family.”

Many of those who are awarded SIVs are in similar positions to Aslamyar: They leave their war-torn homeland, families in tow, in the hope they can provide safety and stability.

Z.B., who asked to remain anonymous, first came to the D.C. area this past march with his wife and their two children from Kabul, after threats against them for his work as a translator who worked in Afghanistan with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Z.B. recently started his first job here in the U.S., as a security officer, but he only makes $220 per shift, three days a week – hardly enough to cover his family’s expenses of rent and utilities, which total $1,700 a month.

“We are struggling to get on our own feet,” Z.B., whose education is in engineering, said to Fox News.

Back in Afghanistan, Z.B.'s work with the DEA would eventually place him and his family in harm’s way.

From 2008 to 2013, he worked translating documents and assisting with training and wiretapping operations, which led to the arrests of up to 300 drug dealers in the Kabul region. He helped stop dozens of suicide bombers before they carried out terrorist acts. He even had a hand in preventing one plot in which three trucks outfitted with bombs were to be used in a June 2012 attack in Kabul.

As can be expected, his work and support of U.S. reconstruction efforts left him and his colleagues targeted by the Taliban and other extremist groups.

“I lost three of my friends because of their support of the U.S. government,” he said. “The Taliban were given all our names. I was in danger, so I applied for my SIV.

The SIV approval process can be a very arduous one for those applying. Z.B. was no exception. His SIV process took 18 months, forcing him and his family to go into hiding until he was approved.

“I resigned from my job because of the threats. We just moved to different locations,” he said. “We moved around in the middle of the night and used fake names. I was worried at that time.”

Eventually, Z.B. and his family were approved to come to the U.S., they spent their first few months living in a one-bedroom apartment with his brother-in-law’s family in Woodbridge, Va.

“My whole family was in the living room while his family all stayed in the bedroom,” he recalls.

With help, Z.B. was eventually able to get his own apartment, but every month is a struggle.

“I’ve had to borrow money,” he said. “It has been difficult.”

Despite the hardship, he is also optimistic and hopes to eventually work in mining engineering. Until then, he remains upbeat, despite the struggles.

“Here in the U.S., so much can be available to everyone,” Z.B. said. “That is something we do not have in Afghanistan.”

“We are hopeful, but it takes time, but we have to get settled. It doesn’t matter what job it is.”