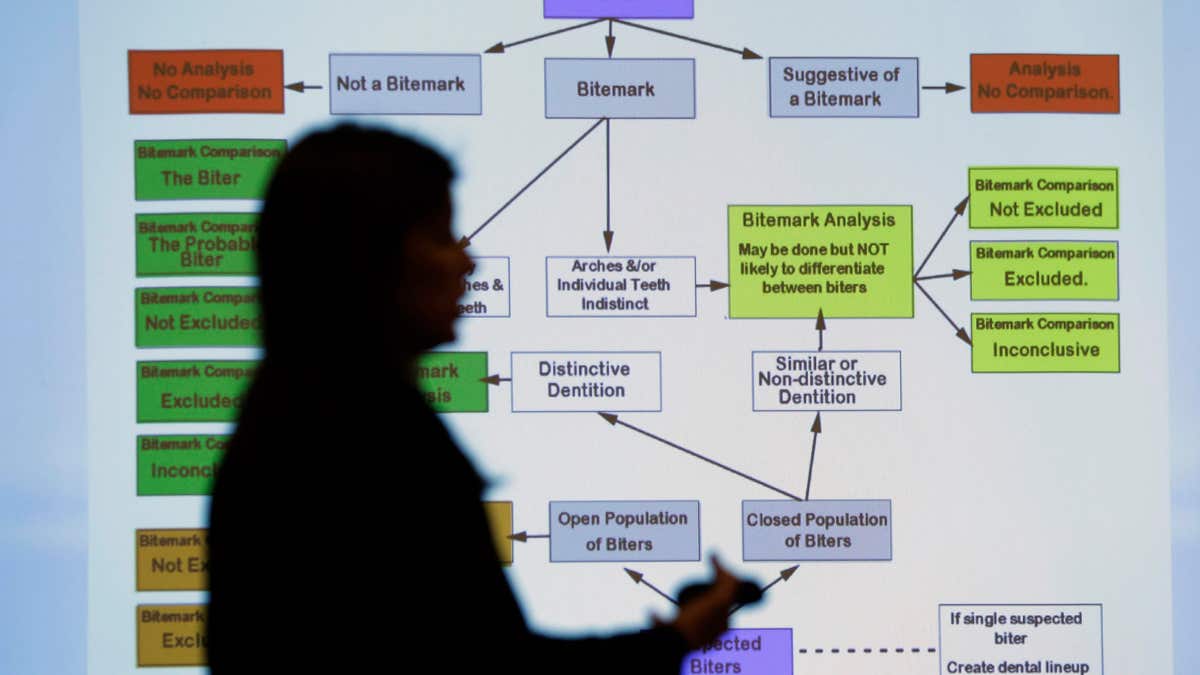

Feb. 11, 2016: Lynn Garcia uses a chart as she takes part in a Texas Forensic Science Commission meeting to consider recommendations against using bite mark analysis in criminal cases/ (AP)

AUSTIN, Texas – Texas became the first state Friday to call for banning bite mark analysis in criminal cases, dealing a major credibility blow to a technique that critics rebuke as junk science and will now likely encounter greater skepticism in courtrooms across the U.S.

Although the Texas Forensic Science Commission doesn't have the power to enforce an outright ban, its recommendation for a moratorium on bite mark evidence is expected to weigh heavily on the minds of judges statewide and beyond. There is no scientific proof that teeth can be definitively matched to human skin.

At least two dozen men convicted or charged with murder or rape based on bite marks have been exonerated nationwide since 2000. Critics say it is long overdue that the practice joins other discredited evidence such as bullet-lead analysis and microscopic hair analysis.

"For far too long courts have permitted this incredibly persuasive evidence that is cloaked in science, when in fact there has been no scientific research to substantiate the practitioners' claims that it is possible to identify someone from a bite mark," said Chris Fabricant, an attorney for the New York-based Innocence Project.

The commission, a state agency whose members are appointed by state Republican leaders, didn't shut the door on supporting bite mark evidence under strict criteria in the future. But commissioners said the burden is now on a small and mostly ungoverned group of forensic dentists who defend the technique to come back with better research.

Supporters of bite mark evidence, who argue the practice has helped convict child killers and serial killer Ted Bundy, told the commission this week that those studies are in the works.

"This should have been going on for years. Hopefully we'll go along a lot faster than we should have been," forensic dentist Frank Wright said.

Putting new scrutiny on bite marks has thrust the obscure Texas Forensic Science Commission into the national spotlight for the second time in recent years. In 2009, then-Gov. Rick Perry abruptly removed three people from the state board just 48 hours before commissioners were to consider a report that a faulty investigation led to a Texas man's execution.

A later ruling by then-Attorney General Greg Abbott, now the Texas governor, effectively ended in an inquiry into the evidence that convicted Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed for the arson deaths of his three children.