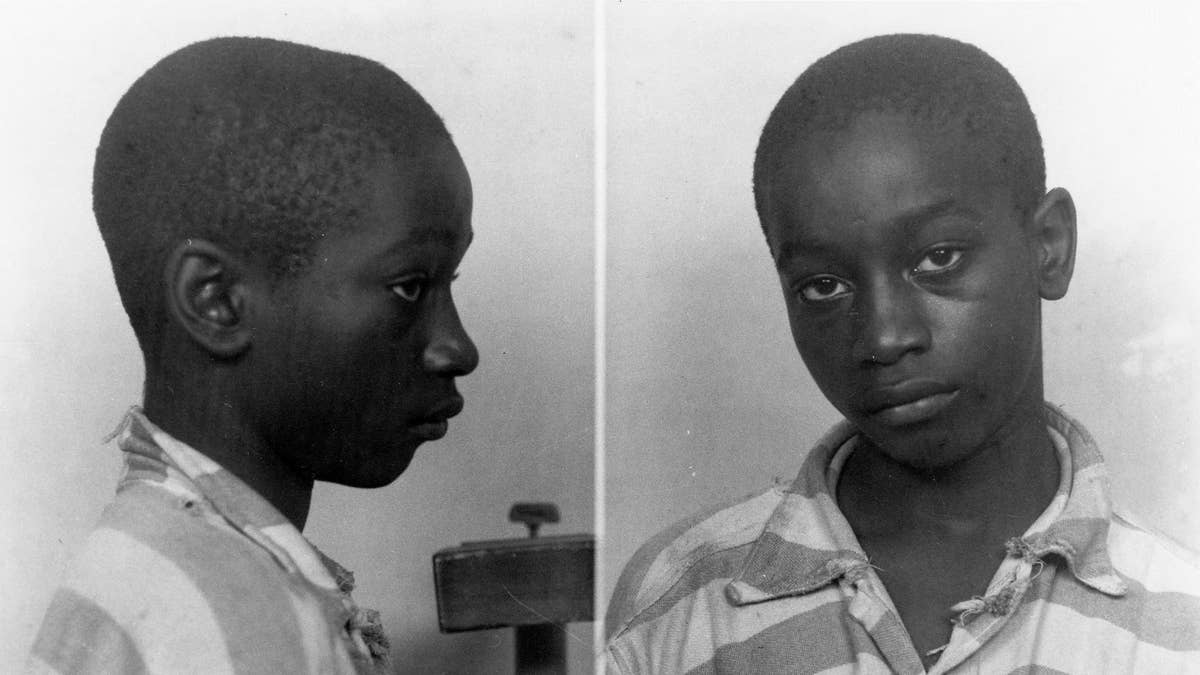

This undated photo provided by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History shows George Stinney Jr. the youngest person ever executed in South Carolina in 1944. Lawyers trying to get a new trial for Stinney say publicity about their case has caused more witnesses to come forward to try to prove his innocence. A judge will hear the appeal for a new trial Jan. 21, 2014. A man who helped pull the bodies of the 7- and 11-year-old from a ditch described exactly where they were found -- several hundred yards from where Stinney, said he saw the girls, according to a brief filed by the attorneys late Friday, Jan. 10, 2014. The boy was out of school for less than an hour that day in March 1944, and it would have likely been impossible for the 95-pound teen to move both bodies such a distance in such a short time span, the lawyers said.(AP/South Carolina Department of Archives and History, File)

COLUMBIA, S.C. – Lawyers trying to get a new trial for a black 14-year-old executed in South Carolina almost 70 years ago for killing two white girls say publicity about their case has caused more witnesses to come forward to try to prove his innocence.

A man who helped pull the bodies of the 7- and 11-year-old from a ditch described exactly where they were found -- several hundred yards from where the teen, George Stinney, said he saw the girls, according to a brief filed by the attorneys late Friday. The boy was out of school for less than an hour while his parents were at a party that day in March 1944, and it would have likely been impossible for the 95-pound teen to move both bodies such a distance in such a short time span, the lawyers said.

Additional evidence included in the brief is a cellmate of Stinney saying the teen told him he was forced to confess and a pathologist who recently reviewed the case and found problems with the conclusions of the autopsy.

"This case has sparked so much interest, these new witnesses were made aware of the case through TV or the newspapers and contacted us with this information," said Matt Burgess, one of the lawyers appealing Stinney's case.

A judge will hear the appeal for a new trial Jan. 21. If the guilty verdict is thrown out, Stinney's lawyers plan to immediately ask the judge to find there isn't enough evidence to try him again.

Solicitor Ernest "Chip" Finney III has said he won't present any evidence against granting Stinney a new trial because almost all the original evidence from the 1944 case, from Stinney's confession to the trial transcript, disappeared. But Finney said he will ask for time to conduct a new investigation if the case is overturned.

Legal experts have said the appeal is a longshot. Stinney, who was black, was executed just 84 days after the two white girls were killed in Jim Crow-era South Carolina, where the legal system routinely found blacks guilty even in cases with scant evidence. The judge will have to take into consideration whether hundreds of similar cases could also be challenged.

But Stinney's supporters point out that at age 14, he was the youngest person executed in the United States in the past 100 years. Stinney was condemned after a trial that took less than a full day, and no record of his confession was ever preserved. The electrodes from the electric chair were too small to fit on his leg, according to newspaper articles at the time.

The statement of the Rev. Francis Batson, who helped find the bodies, shows a conflict of interest that would never be allowed in a modern courtroom. Batson told Stinney's lawyers that a member of the search party whose wealthy family owned the land in the small mill town of Alcolu where the bodies were found ended up as the foreman of the jury that heard the coroner's inquest into the death. That inquest and Stinney's confession were the biggest pieces of evidence against the teen.

Also, the lawyers had pathologist Peter Stephens review the autopsy report on the slain girls. He concluded they were not killed with a railroad spike as the autopsy concluded because the wounds to their heads were not severe enough. Instead, he thinks they were killed with a hammer.

Stinney's lawyers said that is an important conclusion. They say that a railroad spike would have been a convenient weapon if Stinney's confession had been coerced because railroad tracks ran not far from where the girls' bodies were found.