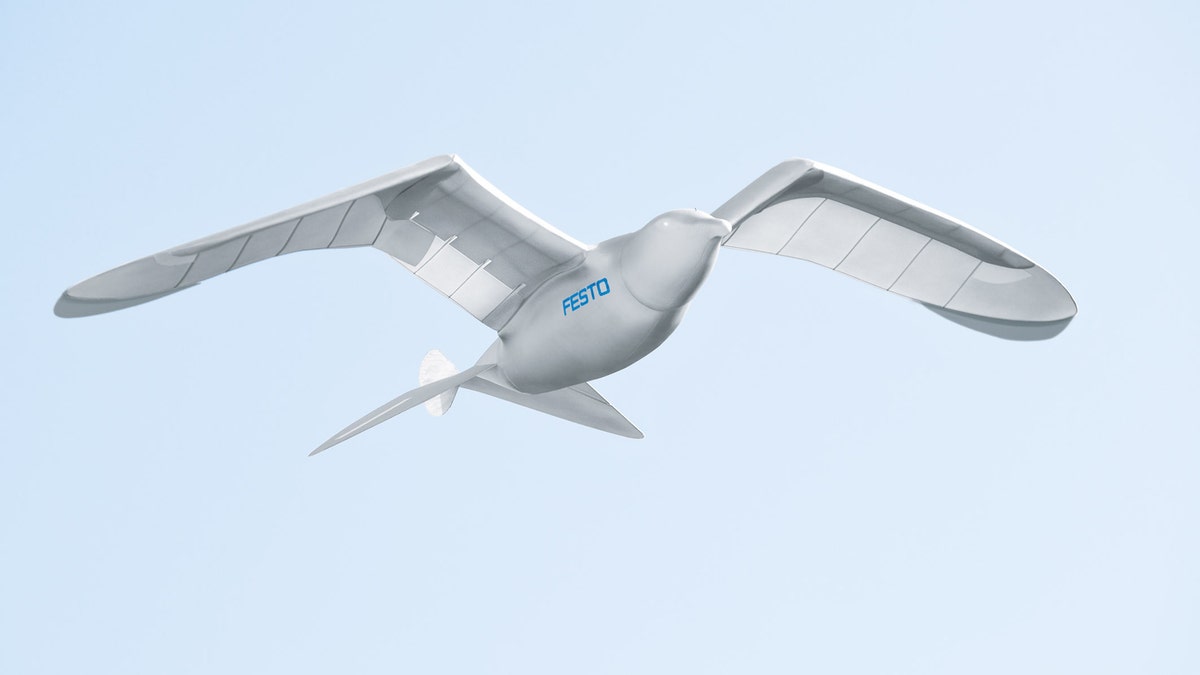

File image of a 'smartbird' (Festo)

China is building an increasingly sophisticated police state and the government’s latest addition to its surveillance apparatus is fake birds that spy on people.

Tiny drones that look like birds and hide in plain sight are a thing, and the Chinese government has been developing its own version in a program reportedly named “Dove”.

According to a report by the South China Morning Post, more than 30 military and government agencies have deployed the birdlike drones in at least five provinces in recent years.

Unlike an average drone, these particular machines are designed to fly by simulating the flight of a small bird — at least in appearance. They look like birds, have a wingspan of about 50 centimetres and can fly at speeds of up to 40km/h, according to the report.

On board is a high-definition camera, GPS antenna, flight control system and data link with satellite communication capability.

The tech is still in its very early stages of development and can be hampered by strong winds, rain or snow, and is vulnerable to electromagnetic disturbance but those involved with the program have high hopes for its widespread adoption.

Yang Wenqing, an associate professor in aeronautics, who is involved with the project told The Post that at the moment the program was still small in scale.

“We believe the technology has good potential for large-scale use in the future … it has some unique advantages to meet the demand for drones in the military and civilian sectors,” she said.

China is not the only country to experiment with the idea of drones disguised as birds, it is simply following in the footsteps of companies in the U.S. and Europe.

In 2013 a Florida-based company called Prioria Robotics sold more than 30 types of drones to the U.S. Army that were designed to look like birds of prey but were eventually accused of being no better than hobby drones.

A Dutch tech firm called Clear Flight Solutions is developing a remote controlled bird dubbed “Robird” which is designed for use in bird control. While back in 2011, a German firm developed “SmartBird” which can fly by itself and was one of the most realistic-looking bird robots but was never released to market.

The Chinese surveillance birds have reportedly been deployed most heavily in the region of Xinjiang, a far-west province of China with a large Muslim population which has long been considered by central Chinese authorities as a hotbed for separatism.

Police use heavy surveillance tactics in the region to help authorities conduct random detentions, forcing the population to spend time in political indoctrination centres in what The Economist recently described “a police state like no other”.

Surveillance cameras and face scans help China make thousands vanish

The development of dove drones is just one of the pieces of tech the Chinese government is attempting to deploy to monitor the behaviour of its citizens.

The Chinese Communist Party is one of a number of governments worldwide to embrace facial recognition technology, but is by far the most aggressive. Police now stroll the streets wearing “smartglasses” with a facial recognition systems, while law enforcement and security officials in China say they hope to use facial recognition technology to track suspects and even predict crimes.

The government is even experimenting with mind reading technology in a bid to extend its reach to the “emotional surveillance” of workers. That experimental program involves headwear with built in sensors, which is being distributed through China’s state-owned companies to monitor the brain waves of their workers.

For years China has tried to keep an iron-like grip on the internet and the online activity of its citizens. It is currently building a society where citizens are given a social credit scores dictated by the government’s view of their behaviour which can even determine a citizen’s eligibility to buy a plane or train ticket, get a bank loan or apply for a job.

This sort of monitoring — both offline and online — and the corresponding social ranking system continues to stoke concerns among human rights groups about the development of a nationwide surveillance system to quell dissent.