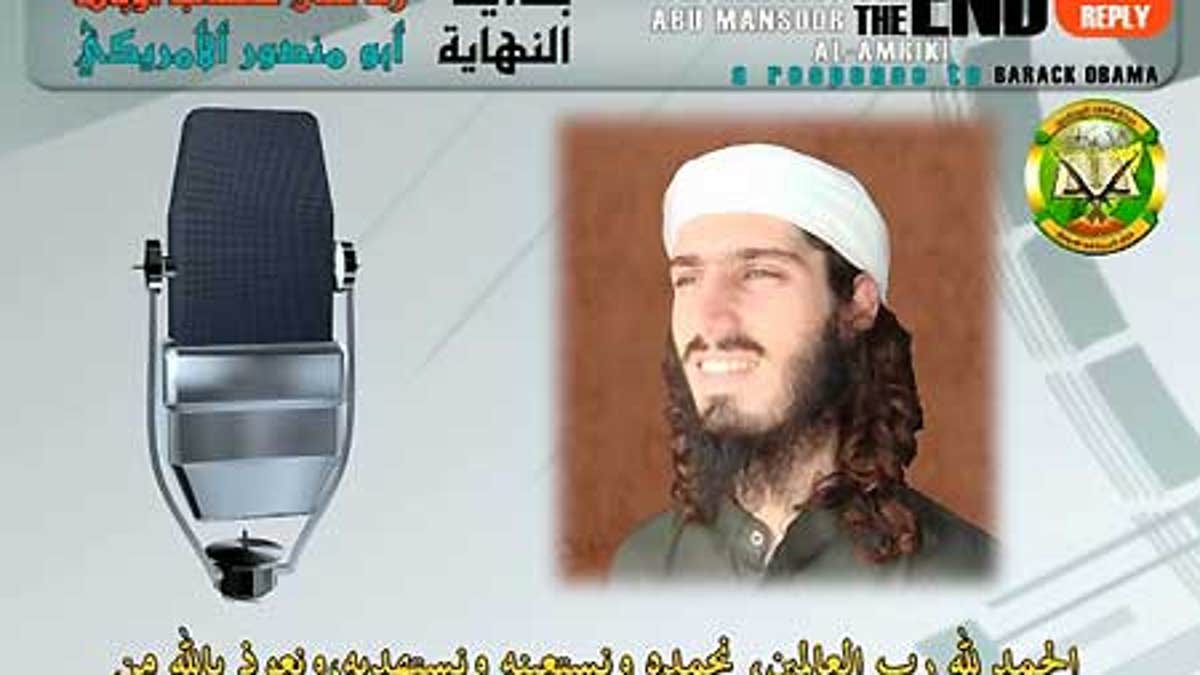

A still image accompanying a new audio tape from Abu Mansour al-Amriki, a member of the Al Qaeda-linked Somali terrorist group al-Shabaab. (Memri.org)

A week after the 9/11 attacks, a young Muslim at the University of South Alabama told the school's newspaper it was "difficult to believe a Muslim could have done this."

Now, eight years later, he is professing to launch attacks himself and calling on others to join the fight, as terror-related charges await him at home in Alabama, FOX News has learned exclusively.

Abu Mansour al-Amriki — or "The American" — has become one of the most recognizable and outspoken voices of terrorist propaganda.

He has been in war-torn Somalia for several years, fighting the secular government there with a group known as al-Shabaab, which has ties to Al Qaeda and was labeled a terrorist organization by the U.S. government last year. Only recently has he taken on a starring — and jarring — role in al-Shabaab's outreach efforts.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation has been looking into him for several years. In fact, a grand jury in Mobile, Ala., has already indicted him on charges of providing material support to terrorists, a source said. It's unclear when the indictment was filed.

Al-Amriki first surfaced in October 2007, when Al-Jazeera TV aired a report about the "common goal" of Al Qaeda and hard-line militants in Somalia. The report described al-Amriki as "a fighter" and "military instructor," but he concealed his face with a cloth wrap throughout the report.

In April, he showed his face for the first time, during a highly-polished, 30-minute recruitment video posted online. It featured anti-American hip-hop and sporadic images of Usama bin Laden.

In the video, he purportedly led a group of al-Shabaab militants in an ambush of pro-government forces in Somalia. Speaking about one man killed in the fight, he said, "We need more like him, so if you can encourage more of your children and more of your neighbors, anyone around, to send people like him to this jihad, it would be a great asset for us."

The violent world that 25-year-old al-Amriki now inhabits is a stark contrast to the sleepy, suburban life he left behind.

He was born Omar Hammami in May 1984, and he grew up outside Mobile, Ala., in the city of Daphne.

Despite inching toward a population of 25,000 in recent years, Daphne still maintains "the ambience of a small town where the people are friendly and caring, and newcomers soon become good friends," according to the city's Web site. The city has streets with names like "Whispering Pines Road."

In fact, U.S. News & World Report calls it one of the "Best Places" in the country. And among Daphne's top assets, according to the city's Web site, are its "reputable schools."

Hammami attended Daphne High School. He was raised Baptist like his mother, but his father is Muslim, and "some time in high school" Hammami converted to Islam, a woman who went to high school with Hammami told FOX News.

The woman, Shellie Brooks, said she is not sure what led Hammami to convert. But the father of a student who went to school with Hammami said Hammami would tell others "he was not fulfilled by his Baptist experience."

Brooks said Hammami would take time out from classes throughout the day to pray.

"It was kind of odd just because it had never been done before," Brooks said. "There weren't many Muslims that went to Daphne High School. He basically just went outside, and you'd see him kneeling and praying as Muslims do."

She said, "Everybody was really accepting of it."

After converting, he frequented the Islamic Society of Mobile, one of the most popular mosques in the Mobile area. A call to the mosque was not returned.

As for Daphne High School, it looks like the all-American high school straight out of the TV show "Friday Night Lights" — complete with the picturesque football field and massive flood lights. Before classes each morning, a small group of students gathers in front of the school to hold hands in Christian prayer. A short time later, a different group carries out an American flag, lifts it to the top of a pole, and stands hands-over-hearts as the "Pledge of Allegiance" is recited over a loudspeaker.

The school's principal, Don Blanchard, remembers Hammami as a good student who didn't get into too much trouble.

"Omar, he was just one of us, he was a good kid," Blanchard said.

Brooks described Hammami as a "very intellectual guy."

"He was in honors classes, and any gifted classes he was in," she said. "He was really well liked. He had a tons of friends, and of course things changed a bit when he converted because his beliefs changed."

According to school yearbooks, Hammami didn't participate in any organized school activities. But his last school photo in 2001 shows a smiling, skinny boy with short hair — almost unrecognizable as Abu Mansour al-Amriki except for the unmistakable nose and ears. That same year, at age 17, he left high school a year early and enrolled at the University of South Alabama in Mobile.

Shortly after he started classes at the University of South Alabama, Al Qaeda launched the 9/11 attacks. A week later, the school newspaper The Vanguard ran a story about the impact the attacks might have on Muslim communities. It quoted the new president of the school's Muslim Student Association: Omar Hammami.

"Everyone was really shocked," Hammami told The Vanguard at the time. "Even now it's difficult to believe a Muslim could have done this."

Hammami told The Vanguard he was worried there could be misguided acts of retribution against Muslims.

"The only way to diffuse this is to get the word out," said Hammami, who would later drop out of college and travel to several countries before landing in Somalia. "With ignorance comes fear and with fear comes violence."

Violence is what Hammami, as al-Amriki, now says is necessary in Somalia — even as he remembers the life he left behind in Alabama.

"The only reason we're staying here away from our families, away from the cities, away from, you know, ice, candy bars, all these other things is because we are waiting to meet with the enemy," he said in the April video posted online.

Blanchard expressed surprise that the person he once knew could now be in Somalia.

"I guess you never know what's going to happen the next day, or what somebody, what influences they may have or come across that leads them on a path other than what it appeared that they might be on," Blanchard said.

Al-Amriki's most recent message came out in July, a month after President Barack Obama promised "a new beginning" with the Muslim world during a speech in Cairo.

"Despite the fact that you have been ... forced [by Muslim fighters] to at least pretend to extend your hand in peace to the Muslims, we cannot and shall not extend our hands," al-Amriki said in an audiotape. "Rather, we shall extend to you our swords, until you leave our lands."

The United States and other countries have recently been assisting Somalia's government in its battle against al-Shabaab. Somalia has had no stable government since 1991, when dictator Siad Barre was ousted from power. A newer secular government has had trouble keeping Muslim militants at bay, and in 2006 fighting with al-Shabaab intensified after Western-backed Ethiopian forces invaded Somalia. U.S. officials say if al-Shabaab prevails, Somalia could turn into a haven for Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

The FBI, in particular, has been keeping a close eye on al-Shabaab's moves. In addition to Hammami's case, for much of the past year the FBI has been looking into how dozens of young men from the Minneapolis area and elsewhere were recruited to train and possibly fight alongside al-Shabaab in Somalia.

In October 2008, 27-year-old college student Shirwa Ahmed of Minneapolis became "the first known American suicide bomber" when he blew himself up in Somalia, killing dozens, according to the FBI. Since then at least four more men from Minneapolis have been killed in Somalia, according to their families.

A grand jury in Minneapolis has been investigating the case for several months, and three men have already pleaded guilty to terror-related charges, including providing material support to terrorists. The indictments said the men traveled to Somalia "so that they could fight jihad" there.

The FBI in Mobile and Washington declined to comment for this article, referring questions to the U.S. Attorney's office in Mobile, which could not be reached.