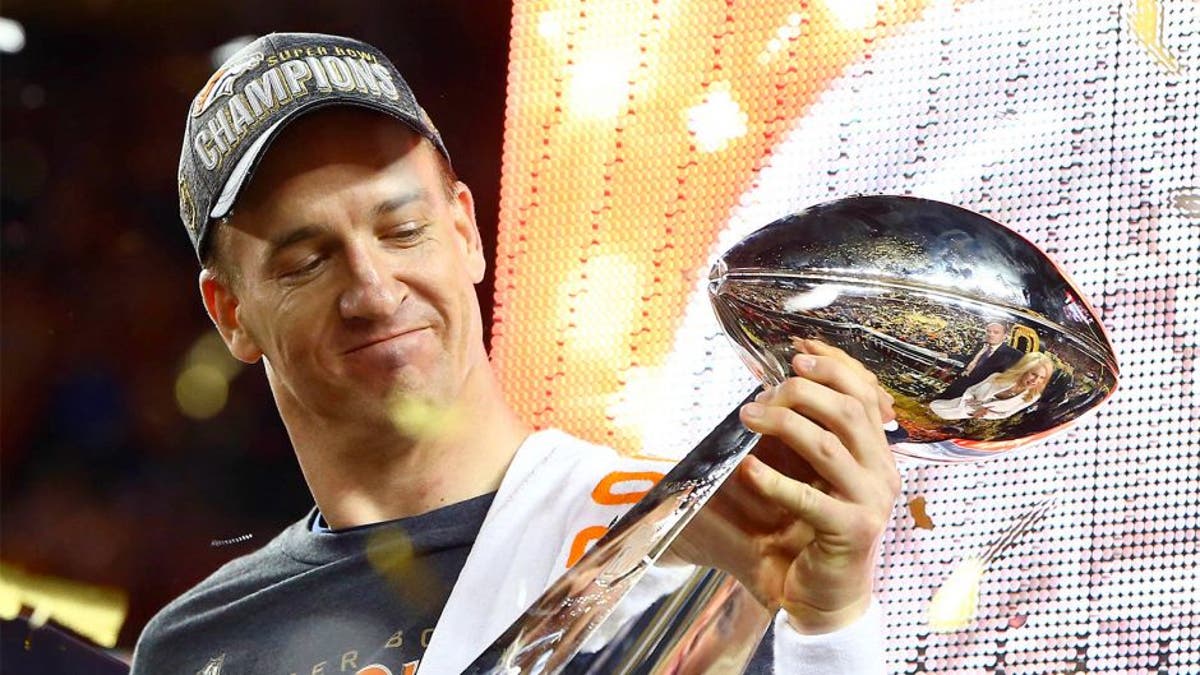

Feb 7, 2016; Santa Clara, CA, USA; Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning (18) hoists the Vince Lombardi Trophy after defeating the Carolina Panthers in Super Bowl 50 at Levi's Stadium. Mandatory Credit: Mark J. Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports

Some have more Super Bowl rings.

Some were better athletes.

Some had more zip on their passes.

Some were more flamboyant.

But there will never be another Peyton Manning.

It isn't just because he heads into retirement on Monday holding almost every major NFL passing record. Or having won two Lombardi Trophies and an unprecedented five Most Valuable Player awards. Or even being the only quarterback to ever post 200 career victories, capped by Denver's 24-10 win over Carolina in Super Bowl 50.

It's because Manning accomplished most of this while playing the game differently than his peers.

Music vernacular best explains the difference. Other quarterbacks were lip-syncing or using auto-tune while Manning was a maestro conducting the orchestra known as his offense.

Manning's gesticulation and "O-ma-ha!" calls at the line of scrimmage usually weren't for show. During the bulk of his time with Indianapolis (1998 to 2011), Manning was calling the game at the line of scrimmage while most of his contemporaries were running the plays their offensive coordinators had sent in, with little wiggle room to make pre-snap changes.

Other quarterbacks from prior generations who Manning will someday join in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, like Bob Griese and Jim Kelly, were renowned for their prowess in doing the same. The big difference, though, is that defenses in their respective, run-heavy eras weren't nearly as complex as the ones Manning faced on a regular basis.

Former Colts general manager Bill Polian told FOXSports.com that the number of times Manning would audible from the play selection in the huddle gradually grew to "60 percent or so." Manning's comfort stemmed from his intelligence, experience and having contributed to the weekly game plan in meetings with offensive coordinator Tom Moore and Jim Caldwell, who was his quarterbacks coach from 2002 to 2008 before replacing Tony Dungy as Colts' head coach.

"What is misunderstood is that Peyton didn't pick the plays out of thin air," Polian said. "He didn't reach into the playbook for a play we hadn't practiced that week. His genius, aided by his incredible preparation, was being able to decipher any defense thrown at him and get us to exactly the right play for that particular defense, including the correct blocking scheme and route adjustments.

"That is a task only a few in the game's history have mastered."

How reliant had Indianapolis become on Manning? The 2009 Colts would have become the first team in NFL history to win a championship with the league's lowest-ranked rushing attack if not for a Super Bowl XLIV loss to New Orleans. And when Manning was forced to miss the 2011 season because of multiple neck surgeries, Indianapolis' streak of nine consecutive playoff appearances ended as the team plummeted to a 2-14 record.

Concerns about whether he could fully recover combined with Indianapolis having the chance to land his replacement, Andrew Luck, with the No. 1 overall pick in the 2012 draft led to the second major chapter of Manning's pro career when he was released and then subsequently signed with Denver.

That's where Manning showed he could not only adapt to a different philosophical approach but flourish statistically like no quarterback has before or since.

The 2013 Broncos set NFL records for points (606) and touchdowns (76) under Manning, who set individual league marks for passing yards (5,477) and touchdowns (55). First-year Miami Dolphins head coach Adam Gase, who was Denver's offensive coordinator that season, is so proud of what was accomplished that he keeps the play-cards from the record-setting games in his new office.

Gase told FOXSports.com that Manning didn't make nearly as many audibles as in Indianapolis. The Broncos used far less verbiage â often relying on a single word to indicate the wide receivers' routes, for example â because the intent was to run plays quickly and keep defenses on their heels.

Rod Smith, who is Denver's all-time leading wide receiver, played on the last Broncos teams to win Super Bowls before the 2015 Manning-led squad. Though Denver fielded prolific offenses in 1997 and 1998, Smith described the 2013 Broncos as "ridiculous" thanks to Manning.

"It's almost like no one is playing defense, but they are," Smith told Broncos media prior to Super Bowl XLVIII. "It just happens so fast with the way that offense is played."

Manning wasn't nearly as flashy in his final season. He was a poor fit for new head coach Gary Kubiak's West Coast-style scheme, where quarterback mobility is emphasized on bootlegs and waggles. Attempts to mesh the things that Kubiak and Manning like proved difficult.

For example, the Broncos installed a pistol formation as a compromise between Manning's preference for the shotgun and Kubiak's desire to have his quarterback under center. It failed to produce the intended results and had a negative effect on others like running back Ronnie Hillman, who said he struggled to see the line of scrimmage and defensive formations pre-snap because Manning and backup Brock Osweiler were so tall.

The negative effect that the neck surgeries had on Manning's throwing velocity and accuracy was more evident than ever as well. After throwing an NFL-high 17 interceptions in the first nine games, Manning was forced to miss seven starts because of a foot injury.

But when he returned to replace a struggling Osweiler, Manning experienced something new even at age 39. Instead of having to carry the team on his shoulders in the postseason, the NFL's top defense lifted him and compensated for Denver's offensive deficiencies. He passed for only 141 yards in Super Bowl 50, with two turnovers, and the Broncos converted only one of 14 third-down plays, but the lasting memory will be of Manning leaving the field as a champion once again.

Kubiak is among those who doesn't feel Manning should have to apologize for becoming a game manager in the twilight of his career.

"The job he did this year to make his way back for our football team was the difference in us being a champion or not," Kubiak said following Super Bowl 50. "What he had to go through physically was very difficult, and it was tough on him mentally. But him fighting the battle to get back, getting himself in position to lead our team again the last month, it says so much about him as a person.

"We all know what type of career he has had as a player, but as a person, it has been tremendous."

The 2015 NFL season also dispels the narrative that Manning is "only" the greatest regular-season quarterback of all time because of past playoff failings. The public debate now shifts to where Manning ranks among the all-time greats. There is no clear-cut answer as to whether Manning should be ranked above or below quarterbacks like Tom Brady, Joe Montana or Johnny Unitas, nor will there ever be.

There are two things, though, that cannot be denied. Manning leaves the game with a style of play that no quarterback in the foreseeable future will duplicate as well as an NFL legacy for which he can be proud.

As Panthers safety Roman Harper said prior to Super Bowl 50, "At the end of the day, he's a winner."

That's all that mattered to Manning and that's how he left the game he loves.