A $6 billion sticking point could create headaches for the U.S.-Cuba talks.

Though concerns over human rights, press freedoms and U.S. fugitives living free on the island have dominated debate over the Obama administration's negotiations on restoring diplomatic ties, the Castro regime also still owes Americans that eye-popping sum.

The $6 billion figure represents the value of all the assets seized from thousands of U.S. citizens and businesses after the Cuban revolution in 1959. With the United States pressing forward on normalizing relations with the communist country, some say the talks must resolve these claims.

"The administration has not provided details about how it will hold the Castro regime to account for the more than $6 billion in outstanding claims by American citizens and businesses for properties confiscated by the Castros," Sen. Robert Menendez, D-Fla., top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote in a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry ahead of historic talks in Havana last week.

Menendez urged the U.S. to "prioritize the interests of American citizens and businesses that have suffered at the hands of the Castro regime" before moving ahead with "additional economic and political concessions."

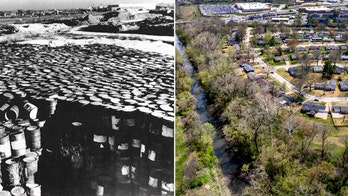

Beginning with Fidel Castro's takeover of the Cuban government in 1959, the communist regime nationalized all of Cuba's utilities and industry, and systematically confiscated private lands to redistribute -- under state control -- to the Cuban population.

The mass seizure without proper compensation led in part to the U.S. trade embargo.

Over nearly 6,000 claims by American citizens and corporations have been certified by the U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, totaling $1.9 billion.

Today, with interest and in today's dollars, that amount is close to $6 billion.

U.S. sugar, mineral, telephone and electric company losses were heavy. Oil refineries were taken from energy giants like Texaco and Exxon. Coca-Cola was forced to leave bottling plants behind. Goodyear and Firestone lost tire factories, and major chains like Hilton handed over once-profitable real estate for nothing in return.

Assistant Secretary of State Roberta Jacobson, after leading the talks in Havana last week, did not mention the U.S. property claims at a press briefing. But a State Department spokesperson later told FoxNews.com the claims "were addressed" in the talks and "will be subject to future discussions."

In Dec. 18 remarks, Jacobson said, "registered claims against the Cuban government" would be part of the "conversation."

She also noted Cuban claims of monetary losses due to the 50-year-old U.S. embargo.

"We do not believe those things would be resolved before diplomatic relations would be restored, but we do believe that they would be part of the conversation," she said. "So this is a process, and it will get started right away, but there's no real timeline of knowing when each part of it will be completed."

The billions are owed, in part, to an array of major companies.

U.S. banks ranging from First National City Bank (which became Citibank) to Chase Manhattan lost millions in assets. According to the list of claimants, the Brothers of the Order of Hermits of St. Augustine even lost $7.8 million in real estate when they were expelled from the island.

According to a government study commissioned in 2007, however, some 88 percent of the claimants are individual American property and asset owners, many of whom would probably like to see some sort of compensation out of the diplomatic deal-making.

"I think this is a significant issue and it has more resonance today than it would have had 20 years ago," as nationalization has seen a resurgence throughout Latin America in recent years, said Robert Muse, a Washington, D.C., attorney who has represented corporate clients whose assets were seized. "You have to take seriously the notion that a government must support their companies when their [property] is expropriated. You have to have some consistency on that."

Experts who spoke to FoxNews.com agree that fully compensating everyone on the list would be a complicated, if not impossible, endeavor.

First, the Cuban government, even if it did agree in spirit to pay, probably would not be able to afford it.

Some individual claimants may be long dead. Further, some of the original corporations no longer exist, thanks to mergers, buyouts, and bankruptcies over the years.

Such is the case with the Cuban Electric Company, which has the largest claim -- $267.6 million in corporate assets (1960 dollars). The company was part of the paper and pulp manufacturer, Boise Cascade Company (which also has a claim for $11.7 million), at the time of the seizures.

But Boise Cascade has since spun off and the part of it that held a subsidiary with a majority stake in Cuban Electric became Office Max -- which later merged with Office Depot in 2013. Company officials reached by FoxNews.com had no comment on the original Cuban Electric claims.

Muse and others, like Cuba analyst Elizabeth Newhouse at the Center for International Policy, say that companies that still have an active interest in getting compensated might agree to more creative terms -- whether it be for less money, or tax breaks or other incentives on future investments if and when the U.S. embargo is lifted.

"My sense is that some corporations are more interested in having a leg-up in any trade arrangements than they are in getting their money back," Newhouse said.

Thomas J. Herzfeld, who heads the 20-year-old Herzfeld Caribbean Basin Fund which trades shares of firms that would have an interest in Cuba if the embargo is lifted, said his life-long goal has been "to rebuild Cuba." He has approached claimants about taking their claims in exchange for investment shares. He said his fund is "well-prepared" for when normalization resumes.

But others warn about popping the corks too soon, particularly if the Castro regime is unwilling to take the compensation seriously. According to the Helms-Burton Act, which enforces the sanctions, the embargo cannot be lifted until there is "demonstrable progress underway" in compensating Americans for their lost property. (Congress also would have to vote to lift the embargo.)

"This is an issue where they are going to have to put their heads together and figure out how to resolve it," Newhouse said. "I think everyone wants to see it resolved."

Jacobson, at the close of last week's opening talks, said there was some progress on opening up embassies, but there continue to be "areas of deep disagreement," particularly on Cuban human rights and fugitives from U.S. justice in Cuba.

"Let me conclude," said Jacobson, the highest-ranking U.S. diplomat to visit Cuba in more than three decades, "it was just a first step."