How can the Ebola outbreak be contained in Africa?

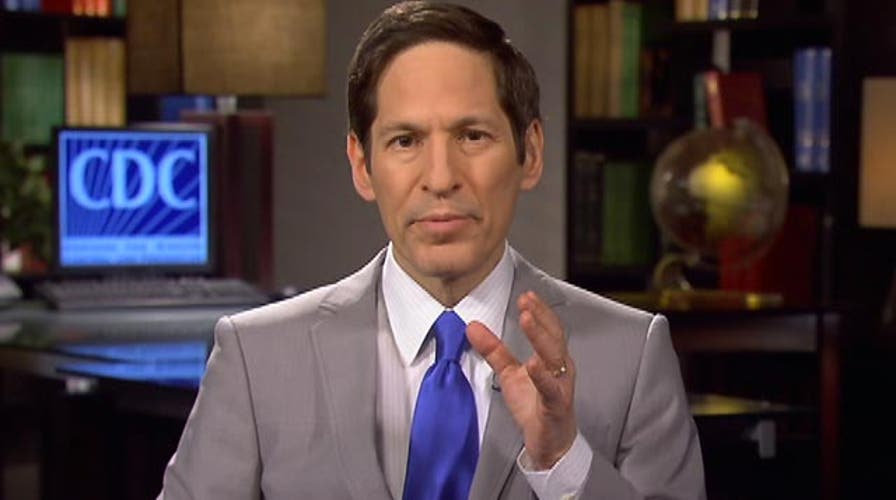

CDC Director Tom Frieden on the strategy to contain the deadly virus

Many have asked questions about the risk of bringing two Americans with Ebola back home to the United States for medical treatment.

Ebola is frightening because it’s so deadly, especially when patients may not have access to basic medical care that can help keep them alive while they fight the illness. This is certainly the case in the three countries in West Africa and in Lagos, Nigeria that are currently fighting Ebola.

There are really two things that have, I am afraid, been confusing in the publicity on Ebola in the past week.

First – is there any effective, proven treatment for Ebola?

Yes, there is! It is basic supportive health care, with fluid management, blood and blood product transfusions if indicated, treatment of bacterial super-infections if patients develop these, and general nursing care. With these core, proven, readily deployable interventions, the death rate from Ebola infections can be cut substantially.

[pullquote]

We hope drugs and vaccines will be available soon. We hope they work, and we hope they can be produced in substantial quantities if they do work. But even if they do work and even if they are available, they would be supplements to, not replacements for, the basic supportive care that is already proven to work. Unfortunately, this supportive care is not in place today for many of the patients who need it in West Africa and Nigeria, and addressing that need is the top global priority.

Second, are special hospital isolation units needed to safely treat patients with Ebola?

No, they’re not! Special facilities aren’t needed, but what IS needed is to be especially careful with standard procedures for basic infection control, which need to be done flawlessly. Ebola isn’t highly contagious – it doesn’t spread through the air, and is far less infectious than the flu or the common cold, for example – but a single lapse can have devastating consequences.

You can’t get Ebola through the air or from water. You can only get Ebola by being in physical contact with the body fluids of someone who is sick or has died from it, or from exposure to contaminated objects such as needles. A patient is not contagious until he or she shows signs of the disease such as fever.

That’s why great care is being taken to help the two American humanitarian workers who have come back home for treatment. As we have done with the handful of hemorrhagic fever patients who have been cared for in various places of the U.S. in the past decade, we have worked to ensure, both in their transport and in their care at Emory University Hospital, that meticulous infection control procedures are being followed.

As an EIS Officer volunteering in a tuberculosis control clinic back in the 1990s, I became infected with the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. I haven’t become ill, but I did have to take preventive antibiotics for many months. In my first week as director of the program that oversaw those clinics, we implemented infection controls that should have been in place earlier, and that would have prevented my infection. It’s my reminder every day of the importance of infection control procedures.

When the organization these humanitarian workers were working for decided to bring these two U.S. citizens home for treatment, their organization paid for their transport and medical care.

It is the role of CDC, and public health agencies generally, to make sure that in doing so we keep the risk of infection to an absolute minimum.

That’s exactly what we have done, and what we will continue to do.

In today’s world of global travel, passengers from areas with Ebola will come to the U.S.

In fact, in the past week, CDC’s experts have worked with doctors, local and state health departments to evaluate – and rule out – Ebola from six travelers who had symptoms that might have been Ebola.

None did. But the fact that we will see more such patients in the coming days and weeks is an indication that doctors on the front lines are doing what they should be doing – identifying patients who might have Ebola, immediately isolating them, and getting them tested for Ebola.

Although there has been intense interest in the two patients at Emory, the real potential for Ebola in the U.S. is not from these diagnosed and medically isolated individuals, but from the traveler who develops Ebola and isn’t promptly diagnosed and put into isolation.

If there is a patient with Ebola in the U.S., CDC has protocols in place to stop spread of the disease. These include notification to CDC of any sick passengers on a plane before its arrival, investigation of sick travelers, and, if necessary, isolation procedures.

We’re alerting health care workers in the United States and reminding them how to isolate and test patients who may have Ebola while following strict infection control procedures.

A person who is sick from the Ebola virus can be safely cared for in U.S. hospitals when the patient is isolated in a private room and contact with them is highly controlled. Health care workers need to make sure they scrupulously follow every infection control protection we recommend.

Right now, Ebola is a huge risk in West Africa. It’s a cause for alertness among doctors and others in the U.S., but it’s not going to be a huge risk in the United States.

As we work to help the communities affected by this virus, we must not let our fear outweigh our compassion.

CDC is in the process of deploying 50 additional health care and disease control experts to the affected regions in Africa to support ongoing efforts to stop the virus where it starts, and working with many U.S. and global partners to surge the response there.

Stopping this outbreak of Ebola won’t be easy, but we know how to do it. We can stop these outbreaks the same way we’ve stopped every outbreak of this virus over the past 40 years – patient isolation, rigorous infection control measures in hospitals, intensive and thorough contact tracing in affected communities, and community education.

The best way to protect Americans from Ebola is to stop it at the source in Africa. And this is exactly what we are working to do.