I have never heard Rome so quiet.

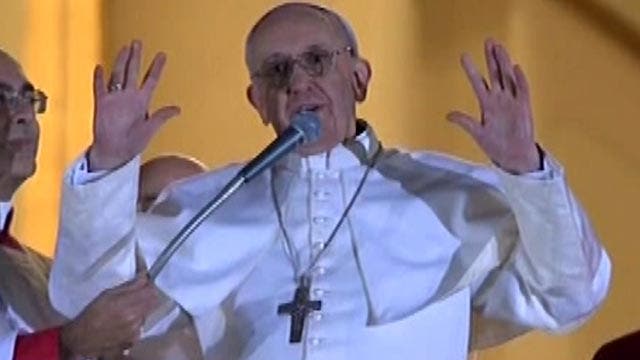

In just a moment, the bespectacled man on the loggia, on whom countless eyes around the world were focused, managed to quell the ebullient, near-frenzied tens of thousands gathered below him in St. Peter’s Square, with a simple request: pray for me.

With those words, Jorge Mario Bergoglio – the newly minted Pope Francis -- bowed his head in submission, and the full-throated throng that seconds before had been shouting “Viva Il Papa,” fell silent, humbled, perhaps, by the new pope’s own humility.

[pullquote]

Within minutes of his first appearance as the 266th vicar of Christ, Francis’s life and career were being dissected for clues to how he would reign and where he would take the Roman Catholic Church that had just been entrusted to him. The most straightforward, and perhaps honest answer is: global.

- Pope Francis captivates crowds with 1st words suggesting agenda of peace and dialogue

- Francis is first pope from the Americas; austere Jesuit who modernized Argentine church

- Argentina, Latin America react with joy at first pope from the hemisphere

- New pope’s name Francis is synonymous with peace, poverty, simple lifestyle

- Now that he’s pope, much on agenda for Pope Francis

- Obama sends prayers, warm wishes to new pope

By installing the first pope from Latin America, indeed, from what used to be known as the New World, the cardinal-electors were recognizing that theirs is the universal church. Its legitimacy rests on its ability to offer salvation to all who follow its teaching, no matter how recently their homelands were introduced to Christ’s message.

As archbishop of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio carved a reputation for himself as a self-effacing spiritual leader who cared about the misery he could plainly see around him. He reminded his fellow Latin American bishops that while the church in the region was growing, it was paying insufficient attention to the poorest of the faithful.

Yet he was not cut from the same cloth as the left-wing Latino priests who created Liberation Theology in the 1980s and tried to bend church doctrine to their temporal political agenda.

Confronted with demands that he side with those who wanted movement on clerical celibacy, and the church’s longstanding opposition to birth control, Bergoglio stood with the traditionalists, angering not only some fellow clergy but also Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who bristled at the archbishop’s refusal to sanction same sex marriage.

Where change can be expected to occur during the reign of Francis is not in the church’s dogma, but its bureaucracy. His by-now famous refusal to live in the archbishop’s palace, and his insistence on cooking for himself and riding public transportation foreshadows what may be a long-overdue housecleaning in the curia, the Church’s de facto government. Petty feuds between bishops that were allowed to fester during the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict XVI may well come to an abrupt, if not gentle end.

The church cannot afford to brush aside scandals like the sexual abuse of innocent victims by its clergy. The Vatican bank cannot continue to flout the financial rules of the rest of Europe – the kind of double-bookkeeping that caused Jesus to lose his temper in the temple, the only recorded instance in the New Testament of literal divine wrath.

An outsider, despite his Italian parentage, Francis may feel no hesitance to take bold steps to quickly clean house in the Vatican’s Augean stables. If a number of sudden resignations and strategic new appointments are announced by year’s end, no one should be surprised.

Francis will also find fertile ground for his gentle message of hope and fairness. A son of working class parents, he is attuned to the needs of the impoverished, perhaps more than any of his predecessors since John XXIII. If his first addresses focus on specific topics of social justice, it may be the result of his pent-up frustration with the increasing gap between rich and poor, not just in industrialized countries, but in his native Argentina and Latin America.

Most of all, this Argentine-born pope has an opportunity – and a platform – to tell Catholics the world over, “We’re together in this. Come help me.” For those who feel that the infighting in Rome over power and policy does not affect their real lives, Francis may be just the face of real-world experience to convince them that the Church that baptized them cares about their problems after the holy water has dried.

The Church maintains its structure and rigid positions on important issues not because it cannot see the world changing, but because change alone is no reason to abandon principle. The cleansing difference that Francis may be able to bring is his years of working with, and for, the poor around him, and molding his church’s strength onto the framework of their suffering.

“Pray for me,” said the new pope. “Lead us,” say the world’s 1.2 billion Roman Catholics. To borrow from the world of commerce – sounds like a deal.