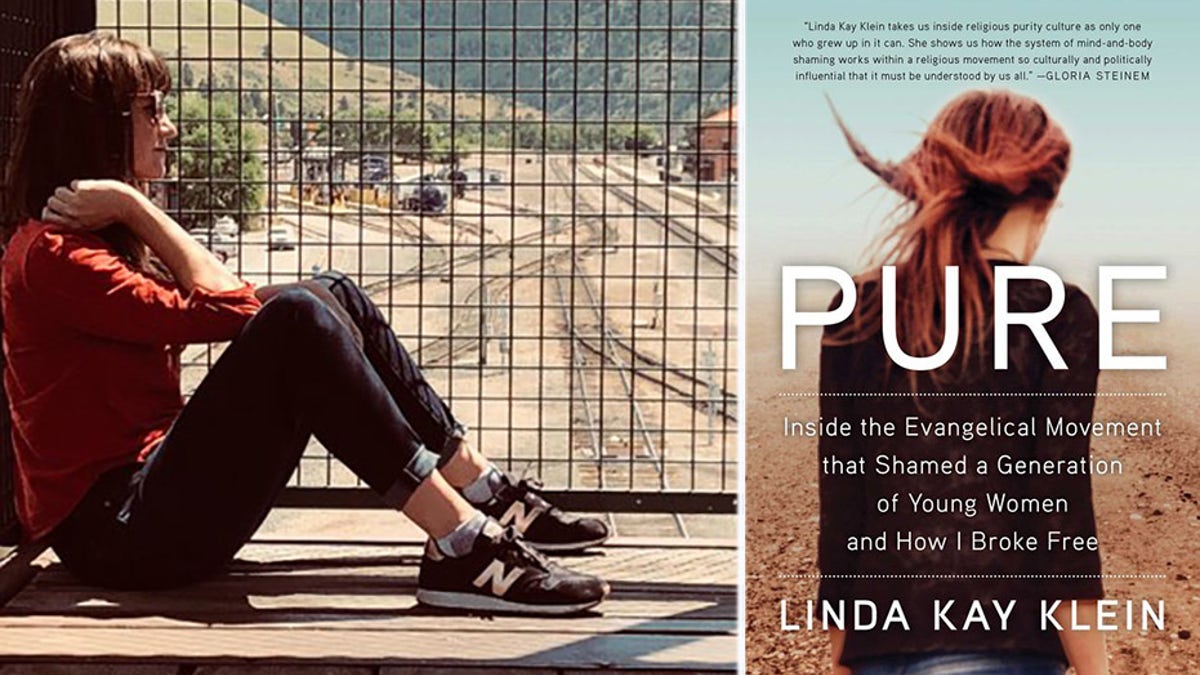

“I realized . . . the problem wasn’t with me,” Linda Kay Klein recalled of her tumultuous relationship with faith in her early life. (Linda Kay Klein Twitter / Touchstone Books)

Before Linda Kay Klein had a routine X-ray at the age of 23, she insisted the nurse gave her a pregnancy test so she would be “better safe than sorry.” It was one of many such tests Klein had undergone over the previous few years because of her fear of having a baby out of wedlock.

Never mind that she was still a virgin.

“I would feel so much tension and anxiety taking the tests,” Klein told The Post. “Deep down, I knew the result would be negative, but I wanted to be sure.”

The excruciating worry was driven by her years growing up as an Evangelical in the Midwest in the late 1980s and early 1990s — and by the purity movement that continues to this day. The first virginity-pledge program, True Love Waits, was started in 1993 by the Southern Baptist Convention and now claims more than 2.5 million pledgers worldwide. Hundreds of thousands of American teens have formally pledged to save themselves for marriage: attending purity balls where they often wear white dresses and are symbolically given to Jesus by their fathers, even accepting rings as vows of their sworn chastity. Although the culture largely consists of girls, boys do take part, including pop-star siblings Nick and Joe Jonas when they were younger.

Now 39 and living in Manhattan, Klein has written “Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free” (Touchstone, out now). Part memoir, part cultural commentary, it chronicles her complex relationship with religion and sex.

“The good girl/bad girl thing is our default way of thinking,” Klein said. “I want to draw attention to the dangers of sexual shaming and purity teachings.”

The writer, who works as a consultant in the nonprofit sector, became a born-again Christian at the age of 13, following in the footsteps of her mother. Klein signed her so-called “purity pledge” at a regional youth gathering in her native Wisconsin two years later, in 1994.

Growing up, she’d been told by pastors and church teachers that she was a “stumbling block” of temptation for boys and men. This was largely presented as her problem, not theirs: It was made clear that she would be cast as a Jezebel — with her character corrupted — if she had sex before marriage.

The message traumatized Klein and many of her peers, sparking fear, anxiety and, in the extreme case of one woman interviewed for the book, the symptoms of anaphylactic shock when she first had sex. (The woman started wheezing and breaking out in welts and wound up in the ER.)

For Klein, the terror was enough that she broke up with her high-school boyfriend at the age of 16 because she was convinced it was God’s will.

“We’d French kiss and every sexual nodule of my body would go off,” she recalled of the ill-fated three-month relationship. “But every shame module in my body was alive, too, because I had been trained [by the church] to feel like that.

“I would beg God to be the refiner’s fire and tear us down so that our sinful desires burnt to a crisp,” recalled Klein. “I wanted Him to remake us into something more holy and pure and some day I could be with [my boyfriend] again.”

These issues continued into her 20s when, still a virgin, she attended Sarah Lawrence College and, later, New York University. By then, she had turned her back on Evangelism after beginning to doubt aspects of its theology — and after a youth pastor at her old church was convicted of the sexual enticement of a 12-year-old girl.

At age 22, she’d been dating a man for three years without having had penetrative sex. She recalls how she would curl up into a ball of anxiety and cry uncontrollably while lying naked in bed with him. Often, she would break out in patches of eczema that she’d scratch until her skin bled.

“The fictions I had learned in church haunted me,” said Klein, who was on birth-control pills at the time. “I thought if you were in a hot tub and someone ejaculated, [sperm] would somehow get over to you. Sex created such a sense of shame that not only could I not have [it], I had nightmares and constant nagging thoughts of how far we had gone sexually.”

The cycle came to an end in her mid-20s after she decided to discuss the damage that the purity ethic had done with female friends back in the Midwest, who admitted they struggled with similar issues.

“I realized . . . the problem wasn’t with me,” Klein said.

She lost her virginity at the age of 26 to a man with whom she’d been in a long-distance romance for about a year.

“The sex wasn’t traumatic, it was quite beautiful because I’d learned, by that point, to separate sexuality from spirituality,” she said. “It felt like a holy experience — as if God was in the room with us.”

Now wed for four years (to a different man), Klein, who is still a Christian, is “very grateful not to have brought any sexual shame into her marriage.”

As the stepmother of a 17-year-old girl, she hopes her book will help other women who have experienced the shame she did.

“The shame we are creating in our culture is not about bashfulness and shyness,” she said. “It is equated with worthlessness and isolation.”

She has launched a nonprofit, Break Free Together, which guides people of all ages on issues of spirituality and sexuality.

“We need to start laying the groundwork for kindergartners to have healthy conversations later,” she said. “There is a need to begin talking about these things early.”